Last week, Web suggested that our government does not have a spending problem but rather a revenue problem. He goes on to point out the vast concentration of wealth among the wealthiest small-percent:

Liberals are often obsessed with keeping taxes highly progressive, but let’s face it – the top 1% control more than 42% of the wealth in the US. If you go to the top 5%, then they collectively control 67% of the wealth in the US. Go to the top 10%, and they control 93% of the country’s wealth.

I don’t disagree with Web that this is problematic. But as Dave later points out, there is a difference between wealth and income. Our federal government taxes the latter. And there are limits to the degree that you can rectify this (in the long, anyway) through tax policy. And it’s even more limited that you can use this in order to bridge our current deficit because any year’s income is only a part of that huge mass of wealth, and the primary form of wealth taxation we have – the estate tax – raises some money, but not huge amounts*. In preparation for a different post, I created a spreadsheet that looks at overall tax burdens of the top earners using numbers from Citizens for Tax Justice (CTJ).

For the sake of this post, I am going to make a rather key assumption or two that are probably not true but that a lot of people assume is: you can tax income more-or-less directly. You can prevent the wealthy from wiggling out of it with a good tax attorney. By raising overall tax rates, you will not see an increase of people looking for deductions or else you can account for it with heavier tax rates. And these heavier tax rates will not result in people doing less work (and thereby paying less in taxes).

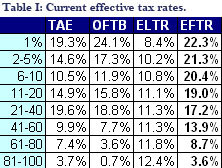

The CTJ numbers are looking at effective tax rates (for households) and not marginal or accumulated tax rates from which many can whittle down their burden through deductions and the like. To the right are the numbers. TAE represents Total Annual Earnings, OFTB represents Overall Federal Tax Burden. ELTR represents effective local and state tax rates. ETR represents Effective Federal Tax Rate. All are represented as percents. On subsequent charts, you will see EFMR, which is the Effective Federal Marginal Rate, and TETB, which is the Total Effective Tax Burden.

The CTJ numbers are looking at effective tax rates (for households) and not marginal or accumulated tax rates from which many can whittle down their burden through deductions and the like. To the right are the numbers. TAE represents Total Annual Earnings, OFTB represents Overall Federal Tax Burden. ELTR represents effective local and state tax rates. ETR represents Effective Federal Tax Rate. All are represented as percents. On subsequent charts, you will see EFMR, which is the Effective Federal Marginal Rate, and TETB, which is the Total Effective Tax Burden.

As Web points out, our tax system is not particular progressive once you get to the top 20%. Especially when you factor in state and local taxes, which are regressive. But right now we’re looking at federal. So if we’re concerned about income inequality, and we’re concerned about balancing the budget, why not just add more progressiveness to the tax code and take care of both!

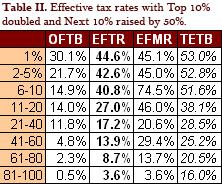

The answer is that the deficit is simply too large. If you were to double the tax rates on the top 1%, you would increase the tax-base by 25%. Now, that’s not too bad… but it’s a first step. It also means that you’re taking over 60 cents on each dollar in the top pseudobracket** if you account for local/state taxes as well. You can extend this downward, but then it starts getting really problematic for people earning money in between the low, existing tax rates, and the higher, new ones. For instance, you can close the entire deficit (almost) by doubling taxes on the top 10% and raising taxes on the next ten percent by 10% by 50%, but now you would be taking over fifty cents on every dollar made over $66,000 (if we include state and local taxes) and almost seventy-five cents of every dollar between $100,000 and $141,000 (after which, marginal rates go down again).

The answer is that the deficit is simply too large. If you were to double the tax rates on the top 1%, you would increase the tax-base by 25%. Now, that’s not too bad… but it’s a first step. It also means that you’re taking over 60 cents on each dollar in the top pseudobracket** if you account for local/state taxes as well. You can extend this downward, but then it starts getting really problematic for people earning money in between the low, existing tax rates, and the higher, new ones. For instance, you can close the entire deficit (almost) by doubling taxes on the top 10% and raising taxes on the next ten percent by 10% by 50%, but now you would be taking over fifty cents on every dollar made over $66,000 (if we include state and local taxes) and almost seventy-five cents of every dollar between $100,000 and $141,000 (after which, marginal rates go down again).

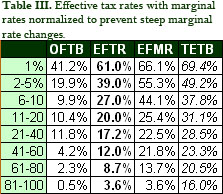

Of course, an odd thing about looking at it this way is that under the previous scenario, marginal rates go down again once you pass $141,000. So let’s say we fiddle with ETRs and make it more directly like a graduated income tax. This means tinkering with the bottom 80%, too, because you run into the same bump for the middle quintile, which pays more marginally than either the second or fourth, but I left their overall burden roughly the same. So if we try to restructure it so that nobody pays more per new dollar earned than those in the previous bracket, you can actually come across something that’s a little more fair in the broader sense. However, you would still have various governments coming after people for more than fifty cents on the dollar for everything they made over $100,000***. The end result of this is a smoother, very progressive system in which the average dollar over $250,000 has almost seventy-five cents taken from it;. And if you’re inclined to cut those between $250k and $1.3m (the average income in the top 1%), you’re going to have to take that much more from the top. That may be satisfying on one level, but exactly how much do we want to take from those that earn good money? Under this plan, the top would lose over 2/3 of their (admittedly, very high) income.****

Of course, an odd thing about looking at it this way is that under the previous scenario, marginal rates go down again once you pass $141,000. So let’s say we fiddle with ETRs and make it more directly like a graduated income tax. This means tinkering with the bottom 80%, too, because you run into the same bump for the middle quintile, which pays more marginally than either the second or fourth, but I left their overall burden roughly the same. So if we try to restructure it so that nobody pays more per new dollar earned than those in the previous bracket, you can actually come across something that’s a little more fair in the broader sense. However, you would still have various governments coming after people for more than fifty cents on the dollar for everything they made over $100,000***. The end result of this is a smoother, very progressive system in which the average dollar over $250,000 has almost seventy-five cents taken from it;. And if you’re inclined to cut those between $250k and $1.3m (the average income in the top 1%), you’re going to have to take that much more from the top. That may be satisfying on one level, but exactly how much do we want to take from those that earn good money? Under this plan, the top would lose over 2/3 of their (admittedly, very high) income.****

I support a progressive tax code (one more progressive than the code we have now). And as I mentioned on Web’s post (and will mention again in a future post), I think that the Truman family’s taxes are going to have to go up even if the folks in Washington manage to cut government. Perhaps it’s merely a product of suddenly being closer to the income where people start thinking that we have too much money and if we’re not turning it into Washington we’re essentially hoarding it, but it’s seeming unreasonable to take three out of four dollars off the top (if you include the state’s cut). The “off the top” does matter, I should add, because I can guarantee you that should something like the above come to pass and the tax burden off of new dollars made reach two-thirds of our income (as it would in the last table), then Clancy and I do start making decisions involving her working less and my not working at all even if more permanent employment does make itself available. And the further down the income line you start the hikes, the higher the marginal rates have to be to make up the difference.

The alternative, here, is to tax wealth itself. Local and state governments do this with the property tax. The federal government does it with the estate tax. I would have to think more about this, though my main concern would be that if it’s too high, you run into a situation where people build companies that they can no longer afford because it’s an asset being taxed. So they’re having to dig into their own pockets just to keep what they’ve built. So while you could do it (and to an extent, it is already done), I don’t know how much revenue you can actually raise from it. Raising the estate tax is another possibility. However, as mentioned in * below, the estate tax doesn’t raise all that much revenue. Too few rich people and they don’t die with sufficient frequency.

This isn’t an argument against raising the taxes on the wealthy (or closing loopholes or whatever). I support the graduated income tax and, as much as we can, targeting taxes to those that can most afford it. But it’s not going to end there. My above assumptions, that we can accurately target these taxes, loopholes will not be created and exploited, and that significant numbers of high-earners will simply trade the thirty-five cents on the dollar that they would otherwise get in favor of more leisure time. Ultimately, unless our economy rebounds in spectacular fashion, the tax punch is going to have to go further than the top 10% or even top 20% of earners, spending is going to have to be cut, or we have to start confiscating wealth/assets.

Which is the main problem with looking at how much the top earners are and thinking that we could close the gap just by taxing them more. The problem is that the top 1% only qualifies as 1% of the population. The top 5% as 5. Meanwhile, the middle quintiles constitute 20% of the population a piece. It’s hard to look at the deficit without also looking at that third of the national income. And at spending. The current deficit, if it continues*****, is not a problem with a simple solution. Nor is it a problem that will be accomplished without pain, as though we can somehow cut huge amounts of spending that nobody will miss or we will simply be able to tax the other guy.

* – Reinstating the Estate Tax to Clinton-levels (18% after the first million to three, 55% of everything after three million) would raise about $10b a year, or .6% of current spending. You can double or triple that by getting rid of deductions or loopholes, and you’re still in the tens of billions and low single-digits.

** – Though this is based on all manner of revenue, for the sake of this data crunching it needed to be simplified. So I’m treating it as a graduated income tax with each bracket beginning after the average income of the previous bracket. Therefore, theoretically, people in the upper half of the 2-5% bracket are getting dinged, too.

*** – This overlooks the distinction between joint and individual filing. Households with more than one potential income get more generous brackets under the current code. There’s no reason why this wouldn’t also be the case for a restructured rigid tax code. But the main difference is that you’d be going after some below that threshold and others above. But it would even out.

**** – Just as a reminder, this is not a high marginal rate from which they’re going to whittle down. Marginal rates were this high when Reagan took office, but even then people did not pay this much in taxes. These are effective tax rates. For all of the deductions we would want to add, we would need to raise the overall rate to be higher enough to compensate.

***** – The Administration’s budget estimations in the future have the gap narrowing. However, this based on the assumption of a huge climb in revenue due to an improving economy and the expiration of the Bush Tax Cuts, which would be the first in a series of hikes from current rates.

About the Author

17 Responses to Shaking The High-Income Tree

Leave a Reply

please enter your email address on this page.

A large part of the problem is the number of loopholes, tax shelters, etc, that are available to businesses, and the fact that businesses that “offshore” their headquarters but do business in the US can hide a ton of money from taxation.

Routing money through a phony headquarters in Ireland, for instance, is a favorite way to hide it from taxation.

That’s one of the problems with corporate taxes. They’re easier to hide and harder to find. They’re also a relatively small part of the revenue budget. Double collections (easier said than done) and you still have a whole lot of ground to make up to meet current obligations.

Speaking of corporate income taxes, the CTJ is not being entirely honest here. The reason the rates for the top quintile and especially the top 1% are so low is that they get a significant portion of their income from capital gains and dividends, which are taxed at 15%. The reason they’re taxed at 15% is that they’ve already been taxed at a much higher rate as corporate profits*.

An honest accounting of total effective tax rates has to take corporate income taxes into account. And when you do that, you get numbers like these.

Also, keep in mind that in the CBO’s charts, “highest quintile” doesn’t mean the 80th through 90th percentiles. It includes the top 10%, which includes the top 5%, which includes the top 1%. So the federal tax system is actually more progressive than is implied by even the CBO’s numbers. If my math is right, the 80th through 90th percentile in 2005 had an average tax rate of around 21%, compared to 31% for the top 1%.

*Yes, I know that sometimes a stock appreciates without the company actually making any profits, but this is in anticipation of future earnings, and ultimately there do need to be profits for a sustainable appreciation in value. While there may be individuals whose capital gains on certain trades are genuinely taxed only at 15%, some shareholders are getting stuck with the tax bill eventually.

This may be a good argument for eliminating the corporate income tax and taxing investment income at the same rate as wage income. It is not a good argument for pretending that shareholders don’t pay corporate income taxes, which was a pretty sleazy thing for the CTJ to have done.

Re corporate income taxes, since Japan recently lowered its corporate income tax rate, we now have the highest corporate income tax rate in the developed world. The bipartisan Bowles-Simpson commission recommended lowering our corporate income tax rate, as part of their overall deficit reduction proposals (in general, they recommended lower rates, fewer deductions, and a broader tax base). Will, I strongly recommend you look at their report. It might save some wheel-reinventing on your part.

Re shaking the high-income tree, I didn’t read this whole post, but a general comment: I think people are willing to pay more in taxes where they get more value in terms of quality government services and infrastructure. That’s not really the case here at the federal level, as I noted in previous tax post’s comment thread. And it’s not the case at the state and local levels either, which is part of the subtext of the current public employee union controversies.

WI and NJ have been in the news in that regard, but a similar dynamic is at work in large American cities with high tax rates, e.g., NYC and Chicago. The wealthy in NYC pay high local and state taxes, but it doesn’t translate into first rate infrastructure or services at all. In fact, the city’s infrastructure is sub par, as are some of its services (e.g., snow plowing). The lion’s share of tax revenues goes to salaries & benefits for public employees and doesn’t trickle down to benefits for tax payers.

Sorry, but I didn’t understand any of the charts. There are no amounts on them, just percents. For example, table one has a 1%, then an EFTR of 22.3% next to it. What exactly is that supposed to mean?

Kirk, the left column is the income group (1% = Top 1% of earners, 2-5% = Top 2-5% earners, and so on). The columns values to the right are explained in the paragraph to the left of the first table. They are in percents as a percentage of income. An EFTR means that they are effectively paying 22.3% of how much they make to the government in various forms of taxes.

The lion’s share of tax revenues goes to salaries & benefits for public employees

Which is a bit of an interesting quirk. Do we either give low salaries for public employees which means some of them end up qualifying for EITC and other tax credits and subsidies, or do we pay them high salaries in order to pay for our high housing costs and to mitigate against any increases in heathcare costs and reduced pension benefits?

David Alexander,

What we should do is set relevant requirements/standards for each job (with respect to education/training, years of experience, aptitude test scores, etc.) and pay enough to attract and retain qualified people in those positions. Public employees should get paid decently. The quid pro quo between public employee unions and the politicians they support took their pay and benefits to unsustainable levels though.

A property tax is actually not very much at all like a wealth tax. The tax assessor doesn’t care whether you own your house free and clear or are 15% in the hole on your mortgage. The only factor that affects your tax bill is the value of your house. It’s really more like a consumption tax on real estate.

The wealthy in NYC pay high local and state taxes, but it doesn’t translate into first rate infrastructure or services at all. In fact, the city’s infrastructure is sub par, as are some of its services (e.g., snow plowing). The lion’s share of tax revenues goes to salaries & benefits for public employees and doesn’t trickle down to benefits for tax payers.

Medicaid is gobbling up an even more disproportionate share of revenues. It’s an example of a program that just keeps growing and growing with no end in sight.

Speaking of corporate income taxes, the CTJ is not being entirely honest here. The reason the rates for the top quintile and especially the top 1% are so low is that they get a significant portion of their income from capital gains and dividends, which are taxed at 15%. The reason they’re taxed at 15% is that they’ve already been taxed at a much higher rate as corporate profits*.

Honestly, we could stop this simply by eliminating the fraud that is “stock options” for employees. Either you buy the stock at market rate or you don’t.

Honestly, we could stop this simply by eliminating the fraud that is “stock options” for employees. Either you buy the stock at market rate or you don’t.

I don’t see how this has anything at all to do with what you quoted, nor do I see why you think employee stock options are fraudulent.

When you exercise employee stock options, the difference between the strike price and the market value at the time of exercise is taxed as wage income, not capital gains. If you exercise 1,000 options at a strike price of $20 when the market price is $30, it’s taxed exactly as if your employer had paid you a $10,000 cash bonus and then sold you 1,000 shares of stock at $30 each.

Brandon, thanks for the heads up about the corporate taxes not being included. Unless someone can give a really good argument otherwise, I think that they should be.

I do wish the CBO would break the numbers down to 1, 2-5, 6-10 and 11-20 since the income differences between these groups can far outstrip the differences between the other quintiles. I’d be interested to know how much more the top 1% pay than the others. Whether they really get nailed or can hire the help needed to avoid it.

Good point about the property tax.

I’m something of a fan of stock options. Falstaff (before everything imploded) was offering them. I think it’s a good way to get employees to “buy in” to the company (one of the few good things Falstaff thought up) that can’t afford to pay them handsome salaries at the outset. When we think of stock options, we often think of CEOs making a bundle, but they’re responsible for helping software developers, chemical engineers, and more becoming millionaires overnight.

That being said, Brandon, I thought that there were some real tax advantages to paying people with stock options. I’ve heard this both from liberals (who consider it a travesty) and conservatives (who cite this as “unintended consequences” and blame the high income taxes). It sounds like you’re saying these tax advantages don’t exist? Or is it that they exist for the corporation but not for the employee?

That being said, Brandon, I thought that there were some real tax advantages to paying people with stock options. I’ve heard this both from liberals (who consider it a travesty) and conservatives (who cite this as “unintended consequences” and blame the high income taxes). It sounds like you’re saying these tax advantages don’t exist?

http://www.bus.wisc.edu/finance/workshops/documents/ilona-babenko110207.pdf

http://www.callancapital.com/news/CC_SDDT-1-24-08.pdf?SourceCode=20070301crj

http://www.ehow.com/list_6849171_tax-benefits-employee-stock-options.html

In short: you only pay income tax if you exercise the option and sell the stock on the same day. The fat cats, on the other hand, shift their income into stock options because by holding it for whatever the perfunctory amount of time is, they can cite it as a “capital gains” tax (much lower than the income tax rate) instead.

Second benefit: capital gains are not subject to Social Security and Medicare taxes.

Third benefit: companies get to expense-deduct the options their employees exercise.

This is why major businesses opt to pay the really high-income folks by stock options whenever possible, why the “corporate raid” strategy (bump the stock price, exercise option, damn the consequences once you leave) is so common, and why I say that stock options ought to be made illegal.

One thing I need to read more on is the comparative advantage of corporate taxation and the capital gains tax compared to simply taxing capital gains the same way we tax other forms of income. It seems if we taxed capital gains like we did other income, this wouldn’t be an issue. I’m not sure of what all of the repercussions of that would be, however.

On the other hand, if we did do what Brandon is saying we do, tax the stock options at the outset, you could still have stock options (which I consider to be a good thing) but without the tax ramifications that Web is concerned about.