This is a setup for an OT post on the UK election.

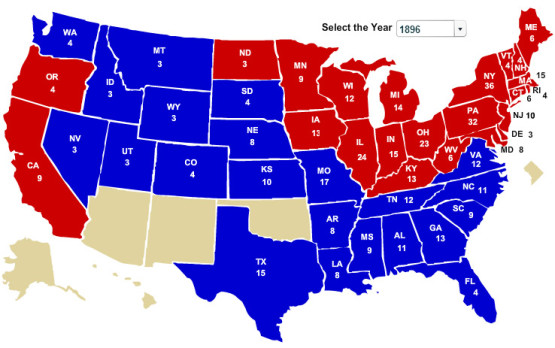

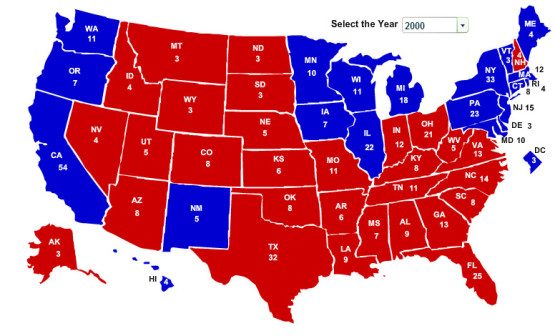

It’s actually a little bit too simplistic to say that “Well, what happened was that the parties reversed themselves from liberal to conservative and vice-versa.”

There is some of that, particularly in the South, but the Great Plains and Mountain West states weren’t particularly conservative, at least as far as economics goes. They voted for William Jennings Bryan, who wasn’t exactly a conservative Democrat. The explanation does carry some weight when it comes to social issues (WJB being famous for arguing against evolution). But one of the stories here is that conservatism won these regions. There is still a degree of economic populism in these states, but that has taken a back seat to cultural alignment.

It actually makes me wonder if there isn’t a lesson here in future realignment, if the Emerging Democratic Majority holds and we need a whole new realignment to get to two parties. It actually wouldn’t surprise me if some of the economic liberally states don’t start pulling back, and some of the current conservative states realize that they need a robust national government. It’s not the most likely scenario, but I could sort of see it. Maybe.

About the Author

7 Responses to 1896 vs 2000

Leave a Reply

please enter your email address on this page.

Oh gosh, it’s infinitely more complicated.

The problem is that political alliances don’t really stay the same over 100 years. For example, in the Civil War New York City was a hotbed of pro-Confederate sentiment because their cotton trade was being screwed up. After that William Jennings Bryan was a Christian, a populist, and a socialist.

The 1896 Republicans were for Northern industrial states, the Democrats for agricultural states and the old South.

The 2000 Republicans were for conservative rural people, the Democrats for liberal urban people.

Think about it–how much does a rural Alabaman farmer have in common with some hedge fund guy in Houston? How much does that hedge fund guy’s media exec college buddy on West 72nd Street have in common with the poor African-American family on West 132nd Street? Coalitions change over time.

Quite so, SFG, quite so.

(And great to see you again!)

Not arguing against the point that it’s more complicated than a flip-flop, but WJB *was* a socially conservative Democrat, was he not? Religious revivalist, social gospel, etc.?

Yeah, but the support for WJB wasn’t based solely (or arguably mostly) on his social views. Some of those same states went for James Weaver in 1892, who ran on a party ticket built around a left-wing economic platform.

It’s a shame if the conversion you’re talking about actually happened, but my guess is that the social conservative strain can be traced back pretty clearly and that ultimately what happened is that it won out over economic issues as social liberalism emerged and grew, not that there was a general liberal -> conservative conversion. In some places, yes, but not all across the plains.

As Michael Cain has mentioned, Socialism and Communism had a lot of appeal among ruralians and farmers and miners.

In 1892, Idaho – today one of the five most conservative states in the nation – gave 54% of its vote to James Weaver of the People’s Party. Pro-business and pro-market Grover Cleveland barely registered in some of the states we’re talking about and he didn’t get more than 20% of the vote in most states west of Kansas City. Then when the Democrats changed trajeIn 1920’s North Dakota, Lynn Frazier was overwhelmingly elected and re-elected governor of North Dakota by a ticket whose platform was for state control of mills. ctory and nominated an economic populist and got the endorsement of the People’s Party, they switched horses. When Robert LaFollette Sr ran a couple/few decades later, he did better in the Mountain West than most of the Great Lakes. It’s something that changed over the course of the second half of the 20th century.

There absolutely was an economic axis at the time, politically speaking, whether we called it “liberal” or “conservative” at the time. There was some combination of pro-business/pro-market/pro-status quo on one end and those who sought radical change on the other, in rough accordance with what we consider right and left today. By and large, they seemed to prefer either a middle ground (Benjamin Harrison) or the latter (Weaver, Bryan). Politics then wasn’t as consistent as politics now, but… it’s there. And it’s there in a way that I don’t think can really be chalked up to things other than economic issues and/or a favoritism towards left economic policy. It’s what, regardless of what they thought about other things (I have no idea what other views Weaver had, to be honest, other than that he was an abolitionist), economics was the campaign that they ran. I really don’t know how you can look at that and not believe that something has significantly changed between then and now.

(The south, of course, is a different bird.)

Put it this way (and maybe this is your point): before the New Deal, to the extent Market Economics was a political force at all, it certainly wasn’t associated with political conservatism in any strong way. You wouldn’t have had people feeling like they couldn’t be for the kind of economics that William Jennings Bryan campaigned on without being unfaithful to a set of generally conservative moral principles. The market economics (libertarian)/conservative politics fusion hadn’t been forged yet.

Point being, I’m not sure it’s historically accurate to see the presence of what we’d now regard as liberal economic views as indicative of the absence of conservative politics. This is something that would tend to preserve the view of continuity between the maps, where eventually native conservatism in these places gets full expression as market economics becomes associated with conservatism. It’s hard to say how much it’s that it becomes uncomfortable to try to unite WJB-style economics with conservatism, versus people becoming genuinely convinced of market economics on the merits. Either ways, the point would be that the issue alliances changed around them, more than that they underwent a genuine liberal -> conservative conversion.

Which is not to say I’m arguing for the continuity thesis across the board, either. Those conversions probably happened. But I don’t think you can pin a theory of genuine conversion on how economic views changed in the region over the course of a century, given how fundamental to identity and politics religion and social issues were from the Civil War to WWII (and before and after).