You may have heard that Austria just struck a huge blow against rightwing authoritarianism by rejecting Freedom Party candidate Norbert Hofer. Reuters said they “roundly rejected” Hofer, Matthew Yglesias is back to mocking the notion that there is any rightwing populist surge, and everybody is pointing out the irony of Austria as a part of the bulwark against right-wing authoritarianism. And I want to bang my head against a wall.

But before we get into why, let’s talk about what this election did do, which is not nothing. First, the bad guy lost. That’s always good! Second, he lost by more in the rematch than he did in the original election. Third, and most importantly, a future constitutional crisis may have been averted. All of this is good news, but more in a “dodged bullet” sense than a “grand victory” one.

The Austrian presidency is on the whole not a very powerful one in function. They have a parliamentary system, and the head of the government is the Chancellor. In terms of government function, the Austrian president looks more like a(n elected) monarch than our own president. So having the presidency does not usually mean very much. In fact, they haven’t even had a president in the last six months or so due to an election over the summer being called into question by alleged voting irregularities, and they’ve had a makeshift arrangement with three co-presidents (including Hofer).

Presidents in such systems tend to be consensus picks (sometimes requiring substantially more than 50% of the vote to take office, though not in Austria). The whole point is that they must be someone that as many people as possible trust and like. If we had such a system in the US, we would probably look to people like Colin Powell for the job. But while the 6.5% (or so) margin may look impressive by American standards, it’s close by Austrian standards. It is, in fact, the second closest election in the last forty years. Heinz Fischer got nearly 80% of the vote in 2010 (though, to be fair, only 52.4% in 2004).

So what was this about a constitutional crisis? Well, a few things. While in effect the President of Austria does not have much power, on paper he or she has quite a bit. They simply defer to the Chancellor. This is also true among some monarchies (and with some of their designates). One difference, though, is that with monarchs there is no pretense of democratic legitimacy. So they have to be really careful with what they do. Otherwise, there’s going to be a crisis. A president elected by the people, on the other hand, might be a different matter. Especially if there is no parliamentary leadership.

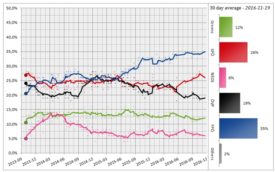

There is a parliamentary election in Austria coming up in a couple of years, and that is one of the reasons I believe that we ought to be very cautious about our victory here. Most particularly because the polls suggest that the Freedom Party is likely to be the top vote-getting party. If the Freedom Party controls the presidency, Hofer could try to insist that the Freedom Party lead the governing coalition. He could, theoretically, let things remain in a stalemate and start making more decisions on his own. Whether this would work or not, I don’t know enough about Austrian traditions and institutions to know, but it seems like a rather unsavory possibility. Alexander Van der Bellen, the president-elect, will instead be able to work around them to assist in the formation of a Coalition of Not The Freedom Party.

There is a parliamentary election in Austria coming up in a couple of years, and that is one of the reasons I believe that we ought to be very cautious about our victory here. Most particularly because the polls suggest that the Freedom Party is likely to be the top vote-getting party. If the Freedom Party controls the presidency, Hofer could try to insist that the Freedom Party lead the governing coalition. He could, theoretically, let things remain in a stalemate and start making more decisions on his own. Whether this would work or not, I don’t know enough about Austrian traditions and institutions to know, but it seems like a rather unsavory possibility. Alexander Van der Bellen, the president-elect, will instead be able to work around them to assist in the formation of a Coalition of Not The Freedom Party.

All of which makes some of the snide commentary from Americans a bit ironic. Yglesias and others have made the comment in effect to say “Weird, the guy who got the most votes won. Imagine that.” Well, for starters, Van der Bellen only won due to a runoff that most Clinton supporters are indifferent to because it should be the person who gets the most votes. Well, unless polls change between now and the next Austrian election, that will be the Freedom Party. Which is precisely the party we don’t want to win even if they do get the most votes. It is, in fact, the diminished possibility of that which is cause for us to express relief. And, of course, Austria has a multi-party system with proportional representation that forms governments on the basis of deals rather than who gets the most votes.

The long and short of it is that it’s true a bullet was dodged. But we shouldn’t exactly be doing victory laps. In the first round of the Austrian presidential elections, the two establishment parties fell short of getting even a quarter of the vote, and both failed to place in the top three. Nearly half of Austrians voted for the bad guy. The bad guys are slated to get a plurality of the vote in two years. If we’re looking for a beacon in the darkness, Austria probably isn’t it.

About the Author

please enter your email address on this page.