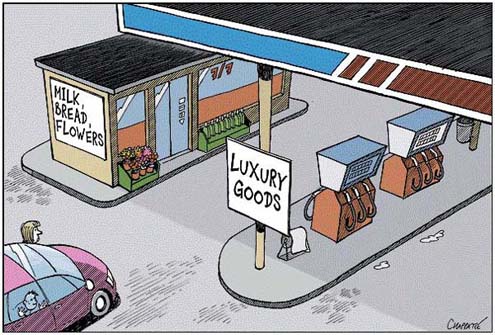

On a couple of occasions, Barry and I have discussed the gas price hikes during hurricane season. For the most part I came to the defense of big oil, explaining that there really were reasons why gas prices would climb so quickly other than the obvious profit motive. The short argument is we have inadequate refining capacity huddled right down hurricane alley. In fact, I am relatively sure that a fair number of gas stations were actually selling it at a loss. There was a flattening of prices for a while, with name gas stations charging only a few cents more than the discounters and only a few cents difference between Delosa (where oil is generally cheap) and Deseret (where it is not so cheap). That’s usually indicative of gas prices running up against an artificial barrier (in this case, the $3 mark. The same thing happened when it hit $2). Gas stations by and large make their money through the convenience stores they’re attached to, and I am guessing that some of them were willing to lose a bit on gas to get people to come in to their stores. Or at least willing to forego much of any profit.

But that’s over now.

I believe my earlier position to be sound, but the situation has changed. The Washington Times outlines it all quite nicely. With the uncertainty gone, the prices should have dropped almost as quickly as they rose. The damage was less than feared (and fear was one of the big things driving the prices upward).

Even our oil-friendly Congress are getting a bit anxious about the prices, and concerns about record profits by the oil companies. I try to avoid getting too political on this site, but it seems to me some assurances of cooperation might have been a good thing to get before the Energy Bill that they got through that was very, very generous to those they are worried about being associated with.

About the Author

12 Responses to The Big Gulp

Leave a Reply

please enter your email address on this page.

We are dropping since the peak here of over $3.50 and now we’re at $2.98 for 87 octane. I’m a little skeptical on how much more we’ll go down, but I’ll take it since it costs me over $60 to fill up my car.

That’s a lot more than it’s fallen out here. We were at $2.99 at the height and are now at $2.75. When all is said and done I think we might be as low as $2.25. I think out here the prices are going to go down because it’ll look an awful lot like collusion if they don’t, just as slowly as they can manage without raising eyebrows.

Our high was about $3.25 at the peak, but it’s back down to $2.41 today. That’s pre-Katrina, by the way, and almost pre-$60+/barrel hikes of mid-June.

Once the arbitrary barrier is broken, it’s not uncommon for it to shoot up even further. Psychologically, the difference between $2.99 and $3.09 is larger than $3.09 to $3.29. I think they take that in to account when setting the prices.

Sounds like the market in Knoxville is much more volatile than that of either of my homes. I wonder how that works. The market in Mocum, where I work, is considerably more volatile up and down than the market in Zarahemla, which tends to move much more reluctantly.

I paid $2.45 to fill up the other day. Our highest was $3.09 after Katrina. I still don’t know why oil companies can profit billions. Yeah, some profit is expected, but record breaking profits when we’re paying records breaking prices? Geez.

Colosse is still at $2.70 average.

This for a town that during the late ’90s was barely breaking $1/gallon while many other places were at $1.25 or more.

Sorry. The phrase “gouging” is entirely apt; prices go up at the slightest provocation, and go down way too slow. Whether it’s gouging by the station itself or gouging by the people selling it to the station, it’s still gouging.

Lass,

I suppose they would respond that this is the payback for when they’re losing money cause prices are so low and preparation in case such a thing happens again. Even if true, however, it certainly creates a problem from a perception standpoint.

Web,

The fact that it’s going down so slowly (at least there and here, faster apparently in Tennessee and Hawaii) is certainly… interesting.

As far as gouging goes, the run-up could be considered gouging, I suppose. The problem is that the word carries with it such negative connotations. It is perfectly rational for prices to go up when there is or is going to be a real or percieved increase of demand or shortage of supply (as was a concern in the run-up to the hurricanes). Not just for the sake of making more money, but to make sure you have enough capital to increase production (if increased demand is the issue) to stay in business (if supply is the issue). It even has the economically efficient effect of allocating resources where they’re most desired (who’s willing to pay).

What’s funny, to me, is that there is no economic explanation behind the ever-so-slowly falling prices except greed. Yet now is when folks are most willing to let the pricemakers off the hook!

All,

If I sound like I’m giving Big Oil a pass, it’s because I’m actually somewhat dispassionate on the subject as a whole. Despite the fact that I pay more for gas than anyone else I know, I lack sympathy for a lot of consumers who (like me) have long commutes or (unlike me) are buying cars that get poor mileage. So absent feeling particularly passionate, I get analytical.

Long commutes: Sometimes, it’s the price you pay for not either (A) living in the slums or (B) paying ridiculously too much in rent.

Cars that get poor mileage: I agree, that’s their own fault.

But put in perspective: my car gets about 27 to the gallon in city driving. Yes, I drive 1/2 hour or a bit more to work, but I also pay a lot less in rent to do so.

I feel particularly passionate because, in true honesty, high gas prices impact me. They might not impact me quite as much if I still lived 5 minutes from work, and they haven’t yet reached the point where paying for the gas is actually worse than paying the more-than-double-what-I-pay-now rent, but it’s still impacting me every time there’s a major swing, because I budget accordingly and it slows me down on paying off various debts I have left over from college.

I can’t imagine what it’s doing to those people who were literally hand-to-mouth BEFORE the gas prices jumped up more than double.

A good rule of thumb is to take the price of gas per gallon and multiply it by 100 and that’s now much it’s going to cost me in gas each month. Roughly $70/week when it was hovering around $3.00. I am more affected by gas prices than anyone else I know. I can’t seem to find work in in the town we live in. You work in a particularly central location in Colosse and living nearby isn’t particularly possible. But a substantial number of people that live in the suburbs do so not because they want a tolerable place, but because they want a bigger one (or consider a normal house by European standards intolerably small, which is equally their problem) or because they want their kid in this school district or that one. There’s nothing wrong with wanting that (just as there’s nothing wrong with wanting a pick-up that can carry large numbers of people), but you factor gas price hikes (and property tax hikes, and car repairs, and so on) into the equation. With any luck, things like this will help people make more environmentally-conscious decisions in whatever way they can both individually (riding the bus if they’re along a busline, buying a house closer to work if they can, buying cars with better mileage, etc) and collectively (governments funding more mass-transit, businesses investing in alternative power sources, and so on).

We also have to remember that high gas prices don’t just affect us in our out-of-pocket gasoline expenses to drive. There’s also increased consumer prices for goods shipped to stores, and a hundred other costs that are raised to compensate for expensive gas.

But, easily put – a gas station pays for gasoline that a distributor sells them, and they get it from…where? The oil companies themselves? Wherever, it’s not important, just that eventually it gets from the refineries to the distributors to the pumps. The refineries either buy the oil or their companies pump it and supply them with it. Either way, there’s a set price they have to incur to pump it or buy it. Whatever their expenses are with markup for a reasonable profit, plus adding a little more here and there down the line until it gets to the pump is how all these links stay in business. The problem is the markup the oil companies charge after the gas leaves the refineries seems to be the real gouge point. That’s where those billions in profits seem to be made, not in the distribution or the stations…. And that’s where our attention should be paid.

Excellent point, Barry. A lot of folks claiming we need a gasoline tax hike to discourage SUVs and long commutes don’t realize the effect it would have on the rest of our economy. To the extent that I’m unconcerned about the issue, I’m probably doing the same.