Over at The American Scene, PEG makes a rousing case for the obligation associated with National Service:

Over at The American Scene, PEG makes a rousing case for the obligation associated with National Service:

f you won the sperm lottery and were born in a wealthy, democratic nation, you have a life whose charm is simply incommensurable and incomparable with the lived existence of the vast, vast majority of human beings who have ever lived on Earth.

You have the privilege of not dying of hunger and easily preventable disease. You have the privilege of having attended schools that, yeah, could be much better, but still taught you how to read. You have the privilege of access to technology and a standard of living that would have been simply unimaginable even to most kings of old. You have the privilege of not having to keep a spare set of clothes under your bed in case the secret police knock in the middle of the night. You have the privilege of being able to spout off whatever nonsense on the internet and not get thrown in jail for your opinions. You have the privilege of medicine which cures most ailments and is relatively available to you. You have the privilege of a relatively much much higher likelihood of having work that is not back-breaking and awful, and perhaps even meaningful and fulfilling. You have the privilege of having a life expectancy which is basically twice the life expectancy of most of the people who came before you. That’s right: you basically have A WHOLE OTHER LIFE on top of your “natural” life, as a reward for the hard work and toil of being born in the right place and the right time.

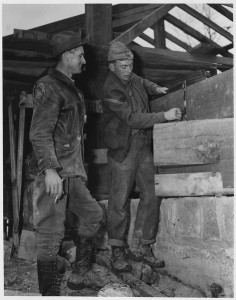

And the simple fact of the matter is that if your sperm was lucky and you were born in one of those countries, the only reason you enjoy this incredible, unimaginable privilege is because people who lived before you sacrificed, and toiled, and gave their lives so that you would have it. They fought wars and they gave their blood and their lives so that a certain political community to which you belong shall not perish from the Earth so that you could enjoy this.

We owe this incredibly charmed modern life not just to scientific progress and capitalism. We also owe it to the stubborn fact that many of our forefathers were willing to put on a uniform, swear an oath, and lay down their lives, for us, their children and their children’s children. Your blessed life is built on the blood and bones of your forefathers.

This will warm the heart of some liberals who have been stressing the social obligations inherent in a society (and some conservatives with their appreciation with upholding a tradition of service). Eat right, don’t smoke, you owe it to your fellow citizens. PEG is falling short of actually making a case for national service because he accepts numerous objections, but he really, really hates the notion of social obligation being laughable or comparable to slavery.

I am of a mixed mind on the subject. On the one hand, PEG truly makes a good case that we are the beneficiaries of a society and there is an obligation associated with that. Yet such a stance often makes me quite uncomfortable. In large part because it is a bottomless obligation. If the government’s investment in my health care gives the government control over what I do with my body, then what we’re talking about actually goes beyond obligation and into ownership. If I am alive but for the willingness of the state (or the community) to keep the barbarians at my gate, then what sense of individuality can I morally claim?

Some liberals mock the rugged individualist, but look: liberals make a big deal out of individuality, too. We all claim certain things – albeit not the same things – as being off-limits regardless of the state’s putative interest in our bodies, our finances, and our relationships. At some point, at least, it’s the healthiest thing to scoff at the notion of an obligation incurred by virtue of either (a) the security afforded by the state and the culture, or (b) the benefits given shared. We can argue that some of the things we do privately aren’t really private and are therefore not subject to approval. And that other things are not sufficiently private because, hey, we are where we are at the pleasure and with the resources of the state.

And so it is with the notion of national services and a draft. I find myself cringing at the notion that of course the state has a right to demand two years of your service.

And yet, and yet, it is quite hard to dismiss PEG’s arguments out-of-hand. Forcing people into military service is perhaps the most intrusive thing that a state can do. But I cannot, out of hand, say that the state should never have a right to do it. I used to make glib arguments that a society that requires a draft to defend itself probably isn’t worth defending. But that’s overly glib and simplistic. Something easy to say when you live in a country without proximate threats to its livelihood.

And if I can, at least in theory, support a draft. And in part on the basis of collective obligation, then national service should be a no-brainer, shouldn’t it?

The answer ultimately is “Yes” that I can support support mandatory service outside of the military just as I can inside of it. It’s just that in the post-Vietnam era, I see non-military as much more ripe for abuse and obligation-creep than military service.

While war has become taken lightly, a war with a draft is unlikely to. And it would require an ongoing, existential threat for there to be a permanent military draft. Otherwise, it’s akin to political suicide to suggest it as anything other than an attempt to make a point about something else (which is problematic in its own way).

I have a harder time coming up with any pressing national need sufficient enough to justify civil conscription. Which, unlike military conscription which requires both the obligation to society and the pressing need, civil conscription would be relying almost entirely on the former with some “Because we want” thrown in there. Because those kids aren’t right.

Ultimately, I have to believe that in order to overturn the presumption of liberty, a case has to be made that is so strong that the obligation we ostensibly have to the greater society is at most a marginal part of that argument. If the solvency of the nation rests in the balance, you institute a draft. If a society depends on somebody going down into the mines, and you simply can’t bribe enough people to do it, then maybe you consider conscription. But as long as you can rely on a volunteer army and you can pay people to go into mines, you simply need not fall to that last resort. Relying on the sence of obligation that PEG refers to so eloquently is, at best, the very beginning of an argument before you get to the actual important part.

Having said that, there is a strong difference between conscription and social pressure that is downplayed in some of the commentary surrounding this issue. I do think that there is value in social expectation of service of some sort. “If you ride alone, you’re riding with Hitler” is worlds apart from mandatory carpooling.

Where I could personally see a role for national service of some sort would actually involve the role that the military has often portrayed in the past: a path for non-college bound young people to have done something worthwhile as a way to avoid the post-high school “drifting” that a lot of people do. Or, honestly, for college graduates who are so inclined. I knock around in my mind some ideas for such programs that might be productive.

I think it’s great that we’re drawing down from war abroad. I do somewhat lament the lost opportunities some may have with the need for less military personnel going forward. And I like the idea of such programs at least on a conceptual level. But I wouldn’t want to go to war to justify such labor utilization, and I have less than a clear idea of what, precisely, we could do with them. Or, for that matter, how we would pay for it.

About the Author

4 Responses to And Everyone Shall Serve…

Leave a Reply

please enter your email address on this page.

I think it is a rare situation where having a draft can be justified, as opposed to just increasing military pay. Maybe WWII, but not Vietnam.

You’re just saying to random young men, we’re going to take 100% of your labor for several years, and put you at a great risk of death or permanent disability, because we don’t want to raise taxes on everyone else by 2% and offer enough money to pay volunteers. I made good use of my late teens, was making three times the minimum wage, and I’d greatly resent having to spend those years doing make-work charity for the same reason.

I can’t disagree with any of this. There has to be an absolute pressing need. Even even then, hopefully you don’t need a draft.

“While war has become taken lightly, a war with a draft is unlikely to.”

Vietnam was objectively stupid at the time. Not as bad as Iraq perhaps. But the draft in place in the early and mid 60’s did not stop it. Also you have to assume a draft that is actually able to force the children of the elite into harm’s way. Otherwise you just have a system, like in Vietnam, that grabbed non-elite young men and taxed 100% of their labor so the elites could pay lower taxes for their war, and at worst had to enroll their kids in part-time national guard work.

I completely agree. History doesn’t bear the theory out. First, the children of the decisionmakers will either find their way out or to plush assignments, generally speaking. But more to the point, I think at most a draft would change the way we fight a war, but not our choice to engage in it. Basically, we’d level Baghdad and run. We wouldn’t bother with nation-building and the like.

On the other hand, that does have a certain appeal…