Dr Phi wants to know why the GOP so frequently seems to have more candidates than the Democrats:

But since 1992, it seems like the Democrat field has never been as crowded. Of the three elections since then in which the Democrats haven’t run an incumbent, the number of candidates with non-trivial delegate counts or vote totals have been:

2000: 2 (Gore, Bradley)

2004: 4 (Kerry, Edwards, Dean, and Clark (barely))

2008: 2 (Obama and Hillary)

The Republicans, in contrast, run more candidates:

1996: 5 (Dole, Buchanan, Forbes, Alexander, and Keyes

2000: 3 (Bush McCain, Keyes))

2008: 4 (McCain, Romney, Huckabee, and Paul)

2012: 4 (Romney, Santorum, Gingrich, Paul)

Which brings us to 2016. The Democrats have two declared candidates (Clinton and Sanders), one undeclared candidate (O’Malley), and one rumored to be testing the waters (Biden). Meanwhile, the Republicans have some 15 candidates serious enough to participate in one of the Fox debates.

Methodology is a bit of a question here. He uses the number of candidates with non-trivial delegate counts. That’s one way of going about it, but it’s a relatively rough measurement for how many candidates each party has. It may well be true that the Democrats weed candidates out more quickly than the GOP – or maybe not – but delegate rules differ between the parties and it excludes entirely candidates that at least in some point in the process had credibility (think Edwards in ’08) and included some with little (Alan Keyes). I also wanted to go back further than 1996.

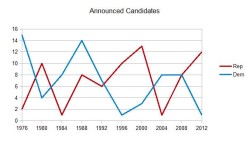

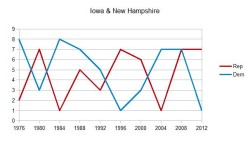

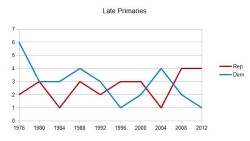

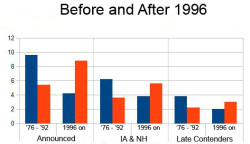

So I looked at three different metrics: How many candidates actually announced (the GOP will have 17 by this metric)? How many were still there in Iowa and New Hampshire (so Perry and Walker would be excluded from this count)? And how many were around for the long haul? The last one was most difficult, but I defined it as getting more than 10% of the vote in any state (excluding their home state) in one of the last 25 primaries. I went all the way back to 1976, which was the second election in the primary era and the first that included competitive races for both parties.

The end result is… well, there’s just not that much difference in the parties in the longer run. Since 1996, there is, but that’s because it excludes the two elections where the Democrats smelled blood and had huge fields and no obvious candidate (1976 and 1988). Since then the GOP had large fields (ten or more announced candidates) three times (2016 is the fourth) while the Democrats haven’t. However, in terms of announced candidates the Democrats actually had eight in ’04 and ’08. But the end result going back to 1976 is that the GOP had an average of 7.1 candidates compared to 6.9 for the Democrats. The numbers don’t actually change all that much if you look at Iowa and New Hampshire or candidates in the race for the long haul. The Democrats have 5 and 2.9 respectively, compared to 4.6 and 2.6 for the GOP.

–

–

–

–

If you look at announced candidates since 1996, you do get the biggest difference of 8.8 Republicans to 4.2 Democrats. By the time we get to Iowa and New Hampshire, there’s still a difference but less of one as there are 3.8 Democrats to 5.6 Republicans. By the end of the primaries, it’s 3 to 2.

So that’s… not insignificant. To the point that it complicates the original “the parties are the same” thesis. The question is, how significant is it? Why has the tide turned? Before this year, the two largest fields were Democratic ones before ’96, but since then the Democrats haven’t hit ten once while the GOP has three times?

So that’s… not insignificant. To the point that it complicates the original “the parties are the same” thesis. The question is, how significant is it? Why has the tide turned? Before this year, the two largest fields were Democratic ones before ’96, but since then the Democrats haven’t hit ten once while the GOP has three times?

The most obvious question is whether this is merely a product of incumbency, but if that’s a factor it’s not an especially large one. Especially over the whole data set, where the GOP had two uncontested primaries (1984 and 2004) as did the Democrats (1996 and 2012). Republicans had contested incumbents in 1976 and 1992, but so did the Democrats in 1980. Broken down to before 1996 and after that does skew things a little bit, but the overall trends hold even if you entirely exclude incumbent party primaries.

One possibility is that there are just random trends and it will go back and forth. Or maybe it’s not random. A theory I can imagine gaining traction is that it coincides with the crazification of the GOP and it’s a symptom of that. If so, though, how crazy were the Democrats during the 70’s and 80’s? Maybe very crazy, if Jane’s Law (“The devotees of the party in power are smug and arrogant. The devotees of the party out of power are insane.”) has any traction. Or if we wish we can come up with a benign reason for one and a less-than-benign reason for the other.

Notably, though, most of the largest fields have come in circumstances like 2016, where one of the parties has been in office for eight years. That ties into my (very tentative theory), which is that large fields come when parties are trying to find themselves and dealing with internal conflict. In 2008 and especially 2000, despite in each case the party being out of power for eight years, there had been a consensus on which direction the party should go. The Democrats had eight candidates in 2008, but they did not represent terribly different visions of what the Democratic Party should be and was mostly a matter of who should advance that vision. In 1976, candidates ranged from George Wallace to Scoop Jackson to Jimmy Carter. It’s more complicated in 1988, but you can still see it. And in 2016, it’s very much there.

That’s just a theory, and not a hill that I am going to die on defending. And it relies on a degree of chance. The problem with the political science of presidential elections is that the sample set is always small. Sure, we are nearing sixty elections, but the facts on the ground change regularly. The parties and issues and coalitions change. With primaries in particular, there have only been eleven elections that they’ve picked the nominee, and those eleven elections have taken us all the way from Vietnam to here.

Perhaps the biggest mystery to me, to be perfectly honest, is why – with all of the senators and governors and celebrities looking for their chance to shine – we don’t have a dozen or more candidates every election.

About the Author

6 Responses to Primary Numbers

Leave a Reply

please enter your email address on this page.

Republicans had contested incumbents in 1976 and 1992

These are both true in only the most literal of senses. In 1976 Ford didn’t do anything to deserve the respect that an incumbent normally gets, having only been elected by the people of Grand Rapids and its district.

You are listing 1992 due to Pat Buchanan’s 26% performance in California, but that was his only significant showing in the last half of the primaries.

Of course, what those incumbents have in common, as well as Carter in 1980 was that they all lost. That makes sense; if your own party doesn’t respect you enough to let you run unopposed, then why should anyone else support you?

True on both counts.

It’ll be interesting to see what happens the next time a president looks really bad for re-election. Whether anyone runs against him or her. Bob Kerrey almost ran against Clinton. Of course, George H Bush didn’t actually look weak when Buchanan announced.

I’d like you to expand on that last sentence because one of my pet theories is that Buchanan’s bid may have helped Bush Sr. more than hurt him, by portraying him (Bush) as more moderate for swing voters. Obviously it didn’t help him enough. And I have no way to actually prove my pet theory.

I don’t think it had much effect either way. Rather, I think that Buchanan identified a weakness in Bush’s prospects that others didn’t see. It’s possible that he sort of drew a map for Clinton, but I don’t especially think so. He was mostly the canary in the coal mine.

Perhaps the biggest mystery to me, to be perfectly honest, is why – with all of the senators and governors and celebrities looking for their chance to shine – we don’t have a dozen or more candidates every election.

The simplest explanation is money, or the lacl of it. But I would have to look at fundraising patterns to see if it can account fur the larger number of R candidates.

For the big campaigns, yeah. But I’m thinking more along the lines of Gilmore campaigns. Spend some time in Iowa, raise some money, have no chance of heck of winning, but get to be on the Big Stage! (I will grant that “shine” here is a relatively low level of brightness, in the greater scheme of things.)

This is especially true of people in the situation that Jindal and Christie are in, where they are in their last term of office, unlikely to really have that much of a future*. You can probably get some (though maybe not a lot) of money not on account that you might be the next president, but that you’re the governor of your state.

(Which does, to be fair, speak rather ill of our system. The quid pro quo there is pretty obvious, though not prosecutable.)

* – That being said, Jindal himself has probably done more harm to himself than any other candidate. He would have been a great candidate for a cabinet post, but I don’t think so anymore. I say “probably” because if Rand Paul loses his senate seat, then that’s one in the hand to Jindal’s two in the bush.