Blog Archives

In Anti-federalist 74, Philadelphiensis wrote,

Who can deny but the president general will be a king to all intents and purposes, and one of the most dangerous kind too-a king elected to command a standing army.

And at the Constitutional Convention, South Carolina’s Charles Pinckney worried that

the Executive powers of the existing Congress might extend to peace and war, etc., which would render the Executive a monarchy, of the worst kind, to wit an elective one.

I understand why they worried about the military power and a standing army, but I’m not grasping why they thought an elected king was worse than a non-elected one. Any thoughts?

At the University of Michigan, a group of cowardly students forced the cancellation of a showing of the film American Sniper, claiming it “promotes anti-Muslim…rhetoric” and “create(s) an unsafe space that does not allow for positive dialogue.” Although I have not seen the movie, the various reviews I’ve seen make it clear that viewers are walking away from the film with different interpretations. Which is to say that it appears to be precisely the kind of movie that actively promotes critical thinking and creates an opportunity for students to engage in productive dialogue.

These efforts–too often successful–to preemptively foreclose debate because it might make some students uncomfortable seem to be growing in frequency. This is a disturbing trend. It’s different from the familiar habit of college administrators trying to squelch free speech because they want a nice, quiet, Stepford campus. This is college students demanding they not be exposed to ideas because they don’t want to be discomfited.

But that’s what education is about. We don’t learn unless we are made uncomfortable. The most well-educated person is the one who regularly reads those whose views are opposed to their own, who can make their intellectual opponents’ arguments as accurately–or even more so–than their opponents can, and who can accurately critique the weaknesses of their own perspective. There’s an old saying that a good research project is one in which you can believe the author’s mind could be changed.

This is the heart of the liberal arts ideal. By studying economics, my views on politics were challenged and changed. By studying anthropology and evolution, my understanding of human nature and the possibilities of human organization were shaped, which structured my views on politics. By studying psychology my perspective on the possibility of markets was refined.

If students refuse to be challenged, they will never become educated. If they run from debate by shutting it down, they will never hear challenges to their perspectives, will never learn the weaknesses of their ideas, will never learn to critically evaluate their beliefs, and will never learn to intellectually defend their understanding of the world around them.

In short, these students have rejected the ideal of the liberal arts education.

The liberal arts are a hard sell these days. People want to know how their course of study will lead to a job. All evidence is that a liberal arts education is a great basis for a broad range of careers, but perhaps too broad, because the direct connections may not exist. I can explain to students how a history major became an international shipping executive, or how an English Major ended up managing international supply chains, but the paths are so contingent, so unique and unrepeatable, that they provide little clear guidance. So students, or at least their parents, shy away from the liberal arts.

And of course careers matter, especially given the cost of college. But the reason the liberal arts are a good foundation for careers is because they train people to think and to learn, to incorporate disparate ideas from different fields and link them together to make sense of things. But not only do too few people see how that connects to careers, they no longer–assuming many people ever did–value critical thinking for itself, for its intrinsic value and the intangible value it adds to the individual’s life. They don’t value it for what it makes of a person.

This is the consequence: students who demand they not be challenged because it is uncomfortable, who demand intellectual safety over intellectual challenge, and who view their epistemic closure as right- thinking.

In the bigger picture this matters because a self-governing republic very well may require an educated populace: people who can think critically about different policy alternatives; citizens who can recognize that their own favored ideas are also imperfect; a public that can understand that vigorous public debate and open discussion of alternatives they dislike is not a threat to liberty but is the essence of liberty; a public that can accept electoral and policy losses without interpreting them as a sign of the system’s illegitimacy.

There is an irony for conservatives here. They have in many ways been at the forefront of the attack on the liberal arts, both because they don’t see enough monetary value in, for example, a theater degree, and because they object to the ways in which liberal academics have challenged their world view and made them uncomfortable. And now there are an increasing number of liberal students taking up that cause and making the same demands, but about conservative views.

And there is also an irony for liberals. In the 1960s liberal students fought for the right to freely discuss and learn about challenging ideas–they fought for intellectual openness. Today liberal students fight against free discussion and teaching of challenging ideas–they fight for intellectual closure.

The American academy is deeply imperiled by a host of factors, including rising costs, a public that doesn’t appreciate what education really does for a person, professors who don’t think it’s their job to teach the public that value (while sneering at them for not understanding it), anti-intellectual administrators, and accrediting agencies that impose ever more inflexible standards that undermine creativity and experimentation in teaching. If the idea of education is assaulted by the students as well, our last best hope for an educated public may disappear.

[Co-published at the Bawdy House]

President Obama has suggested that mandatory voting could offset the influence of big money in campaigns. There’s much that is incoherent in this idea.

First, Democrats are doing as well as Republicans in bringing in big money, but their own electoral failure demonstrates big money itself does turn elections.

Second, the non-voters are generally the least engaged,* who presumably are the most likely to be easily swayed by the advertising of big money, or else might vote essentially randomly.

Third, mandatory voting is illiberal. Forced political participation is another form of social control, rather than a form of liberty. Thorouean types are forbidden. The quiet person who harms no one, pays her taxes without complaint, volunteers in the community, but prefers to not vote is made into a criminal.

Fourth, I object to the instinct to motivate people through punitive action. If as a public policy we want people to vote, then let’s look for positive ways to do so. Traditionally this is done via the parties. Voter mobilization is, in fact, one of the primary purposes of parties, and perhaps the primary purpose.

Fifth, Obama is suggesting that these people should vote for their own good. Mandating that people act in their own interest is perverse, and in my view an improper task for government.

Sixth, it’s not at all certain that big money actually deters turnout, rather than stimulating it.

Overall, it appears to me that the President is concerned about Democratic voter turnout specifically, under the guise of being concerned about overall electoral turnout. He specifically mentioned low turnout among young, lower income, immigrant and minority groups, and criticized efforts to deter their turnout. While it’s fair to argue that efforts to deter turnout are a legitimate public policy problem, the fact remains that Obama is particularly focused on low turnout among populations that he expects to be more supportive of his party, so his solution is not to strengthen his own party’s GOTV efforts, or to find ways to effectively combat voter suppression efforts, but to mandate voting by his party’s likely supporters. Even if successful, though, the lack of close races suggests mandatory voting would have little effect on outcomes.

Under the guise of public policy, this appears to be a means of using law to rig the vote in the Democrats’ favor, no less than voter ID laws are (unsuccessful, I think) efforts to rig the vote in Republicans’ favor, and again under the guise of public policy.

Politicians will normally obscure self-interest behind appealing public interest slogans. They do so because it works, which means appeals like my post here to ignore the slogans will only be effective at the margins.

_____________

*Not solely. I have not voted when I have disliked the options, and I have had a political scientist far more reputable than me assert he gives money rather than voting because it gives his effort more influence.

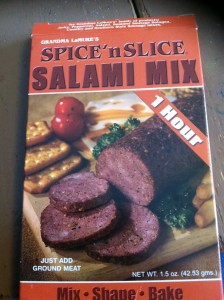

I took a trip to Cabela’s today to look for hiking pants for my daughter before we head to Belize. No luck. We did have a chance to eat elk burgers, though, and then I found this, and thought, heck, yeah, I have to try that.

It recommends 2 pounds of ground beef, venison, turkey, moose, elk, or pork. I interprtehh”kd the “or” as “and,” and in the absence of any wild game mixed a pound each of ground beef and pork together. Together they make excellent meatballs for spaghetti, and salami, spaghetti, it’s all Italian so it has to work, right?

The directions also suggest “adding olive, peppers or other ingredients.” Will do! Scrounging in the fridge I found olives, and capers seemed like a must-do (capers are always a must-do in our house), and sun-dried tomatoes seemed like a good idea, too, but before I found those I scrounged out some sun-dried tomato pesto, and a light bulb went on in my head (but not in my fridge, which has been light bulbless for years, making scrounging more adventurous) that said “even better!”

Everything mixed together with the spices from the packet, and then I hit a small stumbling block–I don’t have a proper baking rack. Well, if this works out well, I’ll get one next time, and meanwhile I’ll just cook it on the big rack in the oven (hoping the meat doesn’t break up and fall through).

Results! That is some seriously strong salami. I like it, but I couldn’t eat more than a sandwich of it at a time. The kids like it, but my wife doesn’t. It’s obviously not going to get eaten quickly, though, so I put half in the freezer for later use. And maybe we’ll have salami sandwiches for dinner sometime this week.

Overall, even if it doesn’t all get eaten, it was worth the ten dollars or so to have actually made my own salami once. And with the spice ingredients listed on the package, I could try mixing my own spices sometime if I want to delve deeper into salami-making.

Sporting events are sub-optimally suspenseful, according to new economic research.

In the context of a mystery novel, these dynamics imply the following familiar plot structure. At each point in the book, the readers thinks that the weight of evidence suggests that the protagonist accused of murder is either guilty or innocent. But in any given chapter, there is a chance of a plot twist that reverses the reader’s beliefs. As the book continues along, plot twists become less likely but more dramatic.

In the context of sports, our results imply that most existing rules cannot be suspense-optimal. In soccer, for example, the probability that the leading team will win depends not only on the period of the game but also on whether it is a tight game or a blowout…

Optimal dynamics could be induced by the following set of rules. We declare the winner to be the last team to score. Moreover, scoring becomes more difficult as the game progresses (e.g., the goal shrinks over time). The former ensures that uncertainty declines over time while the latter generates a decreasing arrival rate of plot twists. (In this context, plot twists are lead changes.)

However in the context of the NBA’s playoff scheduling, “there is an equal amount of suspense and surprise in the 2-3-2 format of the NBA Finals … as in the 2-2-1-1-1 format of the earlier NBA playo rounds.” And in presidential primaries it doesn’t matter what order states go in–you can’t increase suspense by having smaller or more partisan states go first (a counter-intuitive finding, but they’ve got a mathematical proof that’s over my head, so it has to be true).

Hat tip to Marginal Revolution.

So Will admits he tried to bait me into writing about this prof at Marquette U. who’s been blogging about the school, which has now announced they’re revoking his tenure and firing him, which has him claiming they’re violating his academic freedom. Here‘s the prof’s side of the story. In a nutshell, an undergraduate student complained about a graduate student instructor, this prof (from a different department) blogged about it, and the solid waste struck the spinning blades. Will asked my thoughts, a subtle hint that went right over my head as I replied to him via email. Here’s what I wrote.

_____________

Well, he’s a political science prof, so I say fire him.

More seriously, this looks like a case of everyone behaving badly.

1. The graduate student instructor didn’t handle the discussion well. Although despite her being a feminist vegan philosopher, which means I’d probably have extensive disagreements with her, I’m sympathetic because it takes time to learn how to manage students well–after about 14 years I still feel like I’m learning that.

2. The undergrad student is badly mistaken if he thinks he has a right to class discussion on his pet issue.

3. I think the blogger prof is incorrect to call his blog an issue of academic freedom. Not everything we say comes under academic freedom just because we’re academics. For some people that becomes a nice coverall for everything they want to do, without restraint. That doesn’t mean I think there’s necessarily anything wrong with the prof blogging about these things.

4. The Arts & Sciences Dean is probably violating the University’s own policy, as seen in point c here:

“When he/she speaks or writes as a citizen, he/she should be free from institutional censorship or discipline.”

But if the prof is not speaking as a citizen, but as a member of the University, then academic freedom probably does apply.

Marquette is of course private, so it has greater freedom of action here than a public university might, and I don’t find that it has a faculty union (although it might, and I just can’t find a note of it), which would mean the blogger prof has less of a leg to stand on.

For my part, I find it unwise to blog too openly about what happens in my place of work. Some faculty get pretty arrogant and think they’re untouchable and any repercussions for what they say about their place of employment are totally illegitimate. I can’t really speak to the issue of legitimacy of repercussions, but I know from observation that legitimate or not, repercussions do happen, and people who act like they’re immune are idiotic, or, to put it more nicely, un-strategic.

___________________

To add just a bit more, academic freedom is intended to allow people the freedom to research controversial issues, and argue for controversial findings/interpretations of those issues, without repercussions, so we don’t stunt the search for knowledge. Its purpose is not to allow us to criticize our employers (although of course protection for that is nice as well, just for a different set of reasons).

Nor, I think, is academic freedom intended to protect people for any particular political stances they want to yammer about publicly. The University of Illinois, for example, did not, in my opinion, violate the academic freedom of Steven Salaita. But being a public university, bound by the First Amendment, they arguably violated his free speech rights.

And yet I have a hard time imagining the same uproar had Illinois rescinded the hiring of an academic who tweeted that gangbangers were responsible for white racism, as Salaita tweeted that Zionists were responsible for anti-semitism. Defenses of speech and academic freedom are sometimes selective. My graduate program once counted political activity towards tenure, until someone asked what they’d do if they had a politically active white supremacist in the department. That crystallized the reality that it wasn’t really political activism they approved of, but the correct type of political activism, even if those bounds were rather wide.

There’s often a fine line between political activism and academic activity. As an academic I’m persuaded that its foolish for governments to grant rents to firms, but if I stand up at a city council meeting and oppose a tax credit to lure a business to town, is that academic or political? What about if a geologist talks publicly for/against fracking? Perhaps the obscurity of the line is what leads academics to think that any pronouncement they make is covered by academic freedom. And in the Marquette prof’s case, I’m not seeing that journalism, as the professor (correctly) notes he’s doing, about the university itself, counts as academic freedom for a political scientist.*

Whatever the cause, I think we ought to be more humble about how we extend the concept of academic freedom. The step from research findings to applications is so fraught with problems, and with such a history of failure (in all disciplines), that I think we ought to view application, or at least public argument for application, as something distinct from the freedom to research something. Those arguments ought nevertheless be covered by freedom of speech, for those faculty who work at public universities. And private universities would probably be well-served to privately extend a guarantee of freedom of speech as well. But they don’t have to.

__________

*Our faculty union contract with our private college explicitly states that we have academic freedom concerning things in our area of specialty. The Art Historian who makes pronouncements about global warming? That’s not necessarily covered, and I’m not sure it should be. If academic freedom is designed to allow us to learn more about controversial issues, it doesn’t seem intended to protect us in talking out of our asses about things we haven’t actually studied at all.

The Service Employees International Union (SEIU) has proposed that adjuncts should get paid $15,000 per course.

[O]rganizers argue that if you’re teaching a full load of three courses per semester, that comes out to $90,000 in total compensation per year — just the kind of upper-middle-class salary they think people with advanced degrees should be able to expect.

I also teach 3 classes per term, but after 12 years in the business I still don’t get paid $90,000 year. And I have advising, committeework, recruitment, and research expectations on top of the teaching load.

These are folks who think that an advanced degree creates an entitlement, an obligation on others. It doesn’t. And it misunderstands the issue of value.

“It’s not a path to competitiveness to pay knowledge workers bottom-level wages,” says Gary Rhoades, head of the Department of Educational and Policy Studies at the University of Arizona, who has assisted in various adjunct organizing efforts, including the SEIU’s.

This is word salad. Over 20 years ago Paul Krugman pointed out that “Most people who use the term “competitiveness” do so without a second thought.” In Rhoades’ claim, who is in competition with whom, and how does paying adjuncts more than necessary to get qualified ones enhance that competitiveness?

Here’s the ugly truth about adjuncts: there are far too many people willing to be adjuncts for far too many years–their problem is not stingy colleges and universities but the number of other would-be adjuncts competing for the same positions.

What will happen to that number if the pay were to go from around $2500 per class to $15,000 per class? The pool of adjuncts would increase again. People get burned out and quit on adjuncting in part because of the low pay, making room for others to get adjuncting gigs. But if someone can make $60,000/year for teaching 4 classes, instead of $15,000/year for 6 classes (which is not uncommon), they’re not going to clear the field so quickly, and there’s going to be more competition for jobs.

Employing institutions are also going to increase their standards for whom they hire. That guy with the MA and no publications who’s been teaching American Government for us for years? Sorry, we want a PhD with a publication as our adjunct.

And then there’s the question of who pays for this; ultimately it’s going to be the students and/or taxpayers, and they’re not going to get more value for their money. The SEIU doesn’t care about that, though. It’s not their job to care where the money comes from. It’s only their job to gain more dues payers by feeding frustrated academics’ sense of entitlement.

[New guy here, by the grace of Will. I teach political science and political economy at a small private college.]

Wisconsin governor Scott Walker has proposed budget cuts for the University of Wisconsin system and suggested that faculty could help balance the budget by teaching an extra class.

In the future, by not having limitations of things like shared governance, they might be able to make savings just by asking faculty and staff to consider teaching one more class a semester.

There are multiple problems with this statement. First, I wonder if Walker is confusing shared governance with unionism, thinking that the elimination of public sector unions in Wisconsin eliminates shared governance at the university? But unionism is about working conditions, whereas shared governance is about the overall organization, operation, procedures and focus of the organization (e.g., the process for proposing new courses or changes to degree requirements). The boundaries between the two are undeniably blurry–at my own school we often have to pause and reflect upon whether the particular issue we want to address is most appropriately dealt with in the Faculty meeting (shared governance) or in the Union meeting (unionism). It’s a bit amusing, since the two bodies almost wholly overlap, but nonetheless the forum matters. And from my non-expert but not wholly ignorant perspective, teaching load is purely a working conditions issue, not a shared governance issue at all.

Second, Walker makes the basic error of assuming people are just reactive, instead of active: that they will just do as the rule tells them to do, instead of finding ways around the rule. (One of my standing rules of policymaking is to make policy for the people you have, not the people you wish you had.) The top researchers especially will be able to avoid this rule, because they are in demand and will be welcomed at other institutions. In 2009 UW-Madison ranked 9th in the country for federal research funds – receiving almost $600 million – and ranked 3rd in the country for most research and development expenditures, at over $1 billion. Damage UW-Madison’s research program by forcing those professor to spend more time teaching, and you’ll damage the reputation of the state’s flagship institution.

And teaching does take time, not just the hours in the classroom. Even for my most well-prepped class, American Government, I normally put in about 1/2 hour of prep for every hour in class. I know the material, but without review I may not remember all the elements of it that I want to address, or my presentation may not be as orderly and coherent. Imagine memorizing a speech, then giving it twice a year–if you could do it well each time without reviewing it again, my hat’s off to you. New courses, or courses I teach only occasionally, require more than 1 hour of prep per hour in class. That greatly cuts into the time available for research, which is one of the primary reasons faculty at teaching-oriented colleges and universities produce less research than those at research-focused universities.

Then there’s the time spent just thinking. On any given day at any given time someone peering into my office might assume I’m just browsing the internet for cat videos, reading for pleasure, or just staring blankly at the walls. But keeping up with developments in my areas of focus takes time. I not only have to read about them, I have to think about them. I’m familiar with faculty (and administrators) who have skimmed a book or research paper, pulled out an idea couched in memorable phrasing, and then proceeded to misapply it because they didn’t really take the time to think about it. (In one memorable case, as a graduate student I pointed out that a professor had misapplied an important idea from a notable economist, to which he replied, “I guess I ought to read that paper.”)

Thinking takes up just as much time when trying to write a research paper, or any document really. My department completed our program review document last week. On Tuesday I spent most of the day just writing the one page executive summary. (Have you ever tried summarizing a 100 page document in one page, while emphasizing your own tremendous awesomeness and how any imperfections could be solved easily if somebody outside your department would do the right thing while not offending that person who could do that right thing by making it sound like it’s their fault?) On Friday I spent 5 hours reviewing and editing the final draft. And today, Sunday, I am working on a new assignment for my American Government class that will require them to work with real data, which requires long pauses in writing while I think about how to make the directions clear to non-data oriented students.

Teach another class? I’ve actually done a fair amount of that lately, kinda sorta. That is, I’ve taught some overloads lately, but they involve 1/2 courses where I co-teach with someone else, so in a sense I’m only developing 1/4 of a course. It still takes time, though.

This is not to say “pity us poor college profs.” It’s not a bad gig. I worked a lot harder, at much greater personal risk, and for much less pay as a bike messenger. One of my own profs had previously worked at a nitroglycerine factory, until the old guys there–who all had occupational-induced emphysema–told him to get out and go to college so he didn’t end up like them. It’s just to say that the job takes time; that classroom-hours are not synonymous with workload; and that Walker can only get what he wants by damaging the impressive reputation of UW-Madison and thereby diminishing the reputation of the state as a whole.

[Disclosure: I do not teach in Wisconsin or at a public college/university.]