Blog Archives

The Weekly Standard’s Jay Cost is a pretty angry man. A fierce critic of Donald Trump, the primaries did not turn out the way that he had hoped. More to the point, though, he saw it coming. Not Donald Trump specifically, but a broken primary process that was in need of serious reform. Along with Jeffrey H Anderson, he penned an elaborate revamp of the process that would have, if instituted, balanced democratic instincts with establishment prudence. The party paid no heed, and here we are.

Truth be told, I don’t favor Cost’s plan. It would be far too complicated and difficult to understand. If it worked perfectly, it could easily be an improvement over the current system, but it is (as James Hanley described it) a planner’s plan, and bound to frustrate the very people it needs to be sold to. From the party’s standpoint, it would be too expensive. From the voter’s standpoint, they would want to know why they can’t just vote like they used to.

Other people have put forth other radical plans to change the system. James Nevius is the latest in a long line of people agitating for a national primary with a runoff. This certainly looks more attractive to me personally than it did a year ago, but most of my objections remain. A primary calendar allows candidates to build support over time. A national primary would put almost all of the emphasis on media and money, and very little on organization and voter interaction.

Others, like James Hanley, believe that primaries should be done away with altogether because they encourage populism, party office holders shouldn’t be saddled with nominees they don’t support, and committed activists have a better notion of the party interest than casual voters.

A lot of things brings us to the questions, what are primaries for? A lot of people believe that they are mechanisms by which the voters decide who the November candidates should be, but that’s not actually true. Primaries are a mechanism by which a party decides who the best candidate for November is. In the United States, this decision is typically turned over to the voters but it need not be. In fact, in most of the rest of the world, it isn’t. It’s likely to a party’s advantage to have at least a quasi-democratic process in order to make the broader population, and their voters and potential voters more specifically, feel like they are a part of it. (more…)

Verizon’s former pitchman, Paul “Can you Hear Me Now” Marcarelli, has gone with Sprint. Verizon’s response was to concede that Sprint’s network probably is as good as Verizon’s was in 2002. Anyway, I miss the X-Files guy more.

Verizon’s former pitchman, Paul “Can you Hear Me Now” Marcarelli, has gone with Sprint. Verizon’s response was to concede that Sprint’s network probably is as good as Verizon’s was in 2002. Anyway, I miss the X-Files guy more.

It turns out, when the chips are down, doctors die like the rest of us do.

Good news! The rent isn’t quite so damn high anymore. Actually it is, but it’s getting higher at a lower rate, and that’s something.

What? NO!

US versus Canada, the final smackdown.

Buzzfeed may no longer be accepting ads from the GOP, but Washington Free Beacon wants you to know it will not discriminate.

James Pethokoukis takes issue with the recent release about the US being the 41st most entrepreneurial nation in the world.Priceonomics looks at female rulers before feminism, where queens may (or may not) have been more warhawky than their king counterparts.

The thermodynamics formula for calories consumed and burned doesn’t work. Why not?

Tim Harford writes of the real costs of opportunity costs and the power of no.

Space and gravity how do they work?

Of course treadmills got their start as a torture device. Of course they did.

Once we get rid of the Confederate emblem on Mississippi’s flag, and the Union Jack on Hawaii’s, I want to go after state seals next. Relatedly, here are some great and terrible flags of cities in Texas.

Is the problem with psychodelics just dosage?

Vox has a story that is primarily about the voting habits of the wealthy, but talks briefly of education:

There are a few things we know have become very strong predictors of voting Democratic. One is that nonwhite people tend to support Democrats at higher rates than white people do. Another is that the highly educated have become much more liberalover time, making educational attainment a better predictor of voting for a Democrat.

And over time, the top 4 percent has become much more diverse and much more highly educated.

In the context of an article about the wealthy veering towards the Democratic Party, one could easily read this paragraph and conclude that one of the reasons they are increasingly Democratic is that they are more educated, and educated people tend to vote Democrat. You could come to that conclusion because that’s almost exactly what the article says. Almost. It actually makes two comments pertaining to education. First, that the highly educated are becoming liberal. Second, that educational attainment is a predictor for voting Democrat.

Both of these are more-or-less true. Higher education tends to associate with social liberalism, for example. And educational attainment is a predictor for both Democrats and Republicans. Just not in the way that the article implies. Nor in the way that either link lays it out, either. Because the obvious implication of those two statements, that more education generally leads to Democratic voting habits, isn’t especially true unless you look at the data in very specific ways, or look only at one subset of the population.

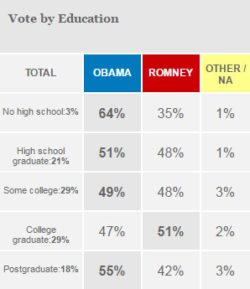

The 2012 data is to the right, and previous years shown below it. You will notice that the one and only group that Mitt Romney wins is college graduates with no post-graduate degrees. This is actually really quite common result. With the exception of 2004, college graduates were the top educational group of Republicans going back all the way to 1988. In 2004, George W Bush did best among “some college” at 54% and then tied among “high school diploma” and “college graduate.” at 52%. For the most part, however, the data to the right is indicative. What it shows is that Democrats do best among the minimally educated and the maximally educated, and Republicans do best in the Great Middle, some college or a bachelor’s degree*.

The 2012 data is to the right, and previous years shown below it. You will notice that the one and only group that Mitt Romney wins is college graduates with no post-graduate degrees. This is actually really quite common result. With the exception of 2004, college graduates were the top educational group of Republicans going back all the way to 1988. In 2004, George W Bush did best among “some college” at 54% and then tied among “high school diploma” and “college graduate.” at 52%. For the most part, however, the data to the right is indicative. What it shows is that Democrats do best among the minimally educated and the maximally educated, and Republicans do best in the Great Middle, some college or a bachelor’s degree*.

So why does the media continue to portray education as having a linear relationship with education when that relationship simply doesn’t exist? There are two explanations that come to mind, neither of which are especially flattering, but both of which are more flattering than “They partisan hacks are trying to trick you!!!!”

So why does the media continue to portray education as having a linear relationship with education when that relationship simply doesn’t exist? There are two explanations that come to mind, neither of which are especially flattering, but both of which are more flattering than “They partisan hacks are trying to trick you!!!!”

Reporters, on some level, simply believe it to be true. So when they look at something like education level and partisan alignment, the data that’s going to jump at them is the data that confirms their impressions. And when they come across data that confirms their impressions, they’re more likely to believe that ought to be a story. A data that doesn’t confirm their impressions won’t necessarily be dismissed as false, but is more likely to be seen as “complicated” rather than a nice, clean narrative like “We’re the educated ones.”

And yes, I do mean “we.” This is an area where it matters that journalists and editors overwhelmingly lean in a particular direction. I mean, do you know how I know that educational attainment doesn’t line up in a linear fashion? Because I took the time to look it up. Why did I take the time to look it up? Because that sounded like an overly simplistic dynamic that didn’t quite correspond with my impressions. There’s that word again: impressions. They matter. Regardless of why newsrooms lean in the direction that they do, it’s not optimal that you have a lot of shared impressions.

In addition to impressions, there is some data. Not the general data, which states what I point out above, but selective data. The data and anecdata that jumps out at you when it confirms your biases. There are three data points that can confirm biases. First, there is a correllation between education level and social liberalty. It just doesn’t cut as cleanly along partisan lines as you might think. More educated Republicans tend to be social liberals, less educated Democrats tend to be socially conservative. Think Country Club Republicans and The Minority Vote.

Second, which is tied to the first, is that the correllation is true among whites. Which makes it sound like “it’s true if you control for race” but it’s not because the opposite holds true for blacks and Hispanics (the educated ones vote slightly less Democratic). And the data for all of this is relatively murky in any event. Too murky to provide any strong narrative, to be honest.

Third, the relationship is accurate if you simply pretend people who don’t go to college don’t exist. If we talk about “more” as getting a postgraduate degree, and “less educated” as merely having a bachelor’s, well there you go. Democrats are more educated. You’ve tossed out half of the electorate and more than half of the population, but those aren’t the people you know, are they?

Which, in addition to confirmation bias, is the source of at least some of this. And is concerning, in its own way. Newsrooms are disproportionately white, and they’re disproportionately educated. The country is (right now) majority white. So when they think of more educated and less educated, they’re likely to be thinking (consciously or unconsciously) “white.” And when they think about who is more educated and less educated, in their world having a postgraduate degree, or a degree from an elite university, does, confirm the bias. Their reality has a liberal bias. I just don’t think they like the omissions that necessarily get them there.

After 2016, this may all be moot, at least for a cycle. It would not surprise me if Hillary did unusually well among those with college degrees and Trump did more poorly. And this could be where the parties are ultimately headed. But they’re not there yet and the trends do not suggest it’s inevitable.

* – This is, it should be pointed out, increasingly what things are looking like with regard to income, which is what the Vox article touches on. Democrats win among the poor, Republicans do best among the middle rich, and Democrats do better and better among the wealthy.

The Internet of Shit has an ominous message for us all:

Now the same is happening with your every day gadgets, but in a slightly more sinister, under the surface way. Companies want to internet-connect your entire house in order to collect more data on you.

The opportunities are delicious for bloated internet companies: now a software company could know how warm your home is, what times of day are noisy, whether you have a pet, when you turn on your lights or if you listen to music while having sex.

Smart devices are sold as a way to improve your life — and in many ways, they do to an extent — but it also means those gadgets are incredible troves of data that could eventually turn into Software-as-a-Service money makers, just like Nespresso did to coffee.

The problem with the Internet of Things is that the hardware is only one aspect. The makers need to keep servers running to support them, keep APIs up to date, keep security up to date and, well, pay employees.

That, eventually, costs more than it does to actually sell you the device. Probably in less than the first twelve months of you using it. That’s not sustainable, and no Internet of Things company has found a better way yet.

If Nest wanted to increase profits it could sell your home’s environment data to advertisers. Too cold? Amazon ads for blankets. Too hot? A banner ad for an air conditioner. Too humid? Dehumidifiers up in your Facebook.

To be clear, that hasn’t happened yet but Nest already shares “anonymous” data with “partners” and Google just happens to be in the business of showing you ads for things. It’s something that will eventuate.

I find myself somewhat less spooked than IoS does about the prospect of such “partners.” My main problem with targeted ads is that the targeting is usually pretty bad. I buy a mattress, suddenly every ad on every site is trying to sell me a mattress. Hey, guys, I just bought one. But when it works, it works. I purchased a couple t-shirts the other day, but there were a couple in the same column that I couldn’t find. Until, that is, a targeted ad just popped up on an unrelated site. Cool!

It’s commonly argued that we should worry more about corporations accumulating data than the government, but it’s just not something I really see for the most part. Corporations are usually trying to figure out the best way to offer me a product at a price that I am willing to pay. I do worry a little bit about increased discriminatory pricing, wherein the listed price is quietly dependent on stuff I’ve purchased and how cost-savvy I am. That seems mostly like an issue that can be addressed independently, though, and I sort of expect the blowback to be worse than any gains they have that over the current system (which price-discriminates based on sales, coupons, etc).

In any event, I found IoS’s comments here odd:

Ten years ago, if you had told people they could make millions off a specific coffee machine that would only take one type of pods, made by the creator of the machine, they might have laughed at you — but then Nespresso came along and ate the world of drink-at-home coffee.

They might have laughed at you… unless they owned a printer. You know, where you pay a pretty decent price for the printer and then have paid for it again two-times over the next five times you replace your ink cartridge? Seriously, such proprietary expenses are pretty old hat. Corporations have been taken to court over it. When I found out about the coffee thing, I didn’t bat an eye. Why would I?

One of the subjects of the piece, Nest, isn’t even doing all that well yet:

A few years ago, Nest was widely viewed as one of Silicon Valley’s brightest stars. Founded by Tony Fadell, a key figure in Apple’s iPod team, Nest aimed to produce a line of user-friendly, connected home appliances. Given Fadell’s Apple background and Nest’s focus on hardware, many people wondered if Nest would become the new Apple.

The company’s first product, the Nest Learning Thermostat, got rave reviews when it was introduced in 2011. Nest added a smoke detector to its product line in 2013. Google was so impressed by the company that it paid $3.2 billion for it in 2014.

But since then, Nest has struggled. It acquired Dropcam in 2014 and rebranded Dropcam’s flagship security camera as the Nest Cam in 2015. Beyond that, Nest hasn’t introduced a single new hardware product, and it looks increasingly unlikely that it can justify that lofty acquisition price. That’s less because of specific problems with the company’s management than because the entire category of internet-connected home devices doesn’t seem that promising.

Late last year, Jesse Singal of NYMag wrote of the left’s war on social science, citing trans researcher Alice Dreger. Last week Dreger had a piece pulled from Feminist Current after an uproar.

Late last year, Jesse Singal of NYMag wrote of the left’s war on social science, citing trans researcher Alice Dreger. Last week Dreger had a piece pulled from Feminist Current after an uproar.

Last year, Max Fisher looked at the potential Third World War.

An interesting look at the relationship between intelligence and heredity.

Whenever I think that eventually people will come around on ecigarettes because the truth will win out, I remember Snus.

Attention Mr Blue! A great New Yorker article on the Spanish Civil War, and the Americans who fought in it.

The heartwarming story of a penguin and a prosthetic foot.

Sara Miller Llana looks at the relationship between religion and support for Brexit.

France’s labor strikes are intensifying. Partially in response to this, President Hollande is suffering from some of the worst approval ratings I have ever seen. One poll has him down to 5%.

Following up on the Thiel/Gawker story, Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry gives a French perspective, and Marc Randazza falls squarely on Thiel’s side.

Donald Trump, it turns out, is not always wrong.

I don’t know if Milo Yiannopoulos is a neo-Nazi, but I do suspect he would find himself doing alright under a fascist regime.

I can understand why Reid has to research Massachusetts’s senate vacancy procedures, since they change the rules whenever the governorship changes hangs. Maybe with a Republican governor, they’ll have the interim elected by state legislature.

This sort of thing has kind of become a thing on Twitter. Not on retweets as here, but the Trump Egg has been replaced by the Trump Supporter With The First Image That Shows Up If You Google Black Guy In A Suit.

Aaron Carroll looks at some negative statistics for home births and takes the very sound view that rather than just discouraging them we ought to make them safer. Amy Tuteur responds.

Amber Lapp says that religions are not doing a good job of making people in non-prescribed family formations welcome, which she says is a problem because that’s where it could be most needed.

Did anybody else have this game? Mohammed Ali was great in it. https://t.co/E6iKnCYGIx

— Will Truman (@trumwill) June 4, 2016

Ali. Both the greatest boxer and boxing's greatest victim.

— John Podhoretz (@jpodhoretz) June 4, 2016

The Champ = my go-to example for worthlessness of IQ as measure of intelligence. The Army said his was 78. Anyone doubt he was a clever man?

— Matthew Walther (@matthewwalther) June 4, 2016

Coach Lombardi saw Ali at a sports banquet, and told an onlooker "What a waste of a tight end."

— Bijan C. Bayne (@bijancbayne) June 4, 2016

Anyone else remember when an interviewer asked Tyson about homosexuality & Alexander the Great? They *really* wanted him to be another Ali.

— Will Truman (@trumwill) June 4, 2016

Don't let Ali be white washed today. The US government tormented him for a reason: he was unabashedly dangerous. pic.twitter.com/JPU2EePOvr

— Dave Zirin (@EdgeofSports) June 4, 2016

Wondering what half of these people eulogizing Ali this morning would've said about him fifty years ago. Pretty sure I can guess.

— Sean Burns (@SeanMBurns) June 4, 2016

Isn’t progress wonderful? https://t.co/hBoVrA7GnJ

— (((Megan McArdle))) (@asymmetricinfo) June 4, 2016

He shook up the world, and the world's better for it. Rest in peace, Champ. pic.twitter.com/z1yM3sSLH3

— President Obama (@POTUS) June 4, 2016

Never knew this: Muhammad Ali Switches His Support to Reagan https://t.co/4MtOaIchKE #MuhammedAli #reagan

— Anil Adyanthaya (@AnilAdyanthaya) June 4, 2016

'The Adventures of Muhammad Ali' aired as part of NBC's 1977 Saturday morning fall lineup pic.twitter.com/idttIlwASh

— RetroNewsNow (@RetroNewsNow) June 4, 2016

As some of you all may be aware, the protests of a Trump rally in San Jose turned violent:

Donald Trump supporters were mobbed and assaulted by protesters on Thursday night after the candidate’s campaign rally in California.

The violence broke out after the event in San Jose wrapped up just before 8 p.m. local time (11 p.m. ET). Some Trump supporters were punched. One woman wearing a “Trump” jersey was cornered, spit at, and pelted with eggs and water bottles.

Police held back at first but eventually moved in. San Jose Police Sgt. Enrique Garcia told NBC News that several protesters were arrested and one officer was assaulted in the melee.

By and large, the response was largely condemnatory, crossing the ideological spectrum. It turns out, violence against attendees of a rally doesn’t go over especially well. For the most part, the main conflict occurred not in whether it was wrong, but why it was wrong. Liberal Chris Hayes and conservative Becket Adams objected to a large number of people framing it as a matter of counterproductivity, saying that it’s not wrong because it’s likely to backfire but it’s wrong because it’s wrong to be violent. Others stuck mostly to tactics. Some, however, objected to the objections:

If you too believe he’s a fascist, then ask yourself what it means to concern troll poor, Latino folks who take that belief seriously.

— Emmett Rensin (@emmettrensin) June 3, 2016

This was itself a common refrain, from several quarters. Epoch Times’s Jonathan Zhou (a Trump sympathizer) used it to blame the media for the violence in a Sarah-Palin-crosshairs-manner. Vice’s Michael Tracey (who seems to support Bernie but also hate people who hate Trump) argued that people need to decide whether Trump is a threat to liberal democracy or whether violence is unjustified because you can’t hold both positions together. This is a refrain I’ve heard quite a bit of in other contexts, mostly from liberals who seem to doubt people like me really oppose Trump: If Trump is so bad, why don’t you take even more extreme measures in your opposition to him? If Trump is a threat to this country, then isn’t anyone who supports him also such a threat?

There is some logic to this. Can we really say that political violence is never morally justified? That’s not a very tenable position in a world where others are quite willing to be violent. War is itself a form of political violence, and most would agree that war is not always wrong. Perhaps it could even be a sort of self-defense. If not personal, then societal. Our ideals aren’t a suicide pact, are they? We can make a somewhat obvious exception in the case of “they started it” or “they were threatening to.” For the most part we grant a pass to the former, though the latter gets trickier. It’s true that most of the circumstances in which violence can be justified will start from one of those two places, but the latter is always tricky and the former tricky once we get past self-defense.I cite Emmett Rensin above in defending the violence, but just last week he wrote a good argument for why punching fascists is morally problematic from a left-wing perspective:

But Marxism and its intellectual heirs reject this notion: People are not autonomous. They do not behave rationally, or freely. There are no wholly culpable autonomous actors, only the expressions of culpable systems. The violence of capitalism, for example, is not the violence of particularly corrupt individuals but the inevitable product of a material structure. Some individuals may resist or relish their role, may err on the side of restraint or of excess, but their choices are not truly their own. One can imagine a Bastille Governor who did not order his troops to slaughter peasants, but this only reflects the routine imperfection of all systems. Such a choice would be an aberration: the historical force of the Ancien Regime was designed to open fire.

It has always seemed to me that collective theories of politics would therefore resist political violence. It is easy enough to justify the occasional murder of an actor if you believe his crimes begin and end with his own choices. But if entire classes are the engine of any political crime, then a politics that justifies the killing of those responsible does not end with an execution. It ends with a holocaust. I have always hoped that this inevitability would make collectivists wary of political violence, the ends of its logic too horrifying and too clear. But history contradicts my hope. When the left has seized power, it has always found kulaks to liquidate, great leaps to take forward. It has taken precisely the nightmare that arises from Robespierre’s excuse and applied it on a grand scale. Of course no individual is wholly responsible for its crimes, it says. That’s why we have to liquidate all the kulaks.

From a personal standpoint, and quite selfishly, I cringe at the violence in part because I don’t know the extent to which the actors recognize the difference between a real fascist and someone who supports policies that some people would argue are “fascist.” The Trumpers have argued that these protests aren’t about Trump but are about disagreement, and implicit in that is “If they weren’t aiming at us, they’d be aiming at you.” If political violence becomes normalized when disagreement becomes facism, communism, or whatever, then really nobody is safe. A willingness to allow people to air their views is one part idealism, and one part non-aggression pact.

So we’re left balancing both the acknowledgement that sometimes violence is necessary, but also that it’s really hard to justify. So the question becomes, “When is political violence justified?” I would argue that there are three main criteria: Whether the threat is sufficiently certain and dire, whether violence helps lower the odds or mitigate the damage, and whether there are alternative means to that same end. Before I go through them one by one, it’s important that we establish the moral case against punching people with bad politics. It might be easy for someone to convince themselves, for instance, that if they support violent policies then we too should be able to be violent!

One of the perennial philosophical debates is whether or not one would kill (or kidnap) Baby Hitler to prevent the Holocaust and World War II. Different people come to different conclusions, but all of them rely on foreknowledge of just how dangerous Hitler became. We have no such knowledge of any current figures. We’re all guessing. They’re not guesses in the dark, to be sure, but they nonetheless require a lot of caution. This is especially true when it comes to Trump, whose political philosophy is inconsistent and ill-determined. I look at him and I see someone who sees nothing beyond himself, and his conception of self is with indifference to – or more accurately hostility towards the rules and constraints that keep our demons at bay.

Others, however, don’t see that at all. They see someone who talks spit and likes to stir things up. Or they see him as a weapon against something more nefarious. Or they view the rules and constraints as not keeping our demons at bay, but leaving us vulnerable to bigger and badder demons that would do us harm. I believe all of this is wrong, but I do not know it to be the case. He has, after all, been a functioning member of the business community for decades and has sufficiently conformed to their norms to still be a figure. As such, I have to at least leave room for people who see him differently and also believe that they do not deserve to have their faces punched in.

There is, ultimately, a difference between the fear that Trump is a demagogue who will destroy everything and the knowledge that he is. Likewise, there is a fear of something as a remote possibility and a fear of something as a likelihood. Trump represents something of a low-probability, catastrophic-consequence scenario. The worst scenario makes a lot of very vocal opposition and heated rhetoric justifiable. However, it also falls short of violence to his supporters in good part due to probabilities. There needs to be more certainty.

Political violence can be effective in a real-life revolution. It can be effective if you have sufficient strength to instill fear one way or another. This will often require you having the implicit or explicit support of the authorities though, or that you are one of the authorities. You need to be able to credibly present a threat going forward, and one that can’t or won’t be responded to with sufficient force to prevent it. It can also be effective if you can provoke the other side into becoming even more violent, though that might be bad for your health.

To the consternation of Hayes and Adams, a lot of people have skipped straight past the morality of the question straight to this one. But it’s an important question and one that, if successfully argued, makes the moral question moot. Because even if we agree that violence can be justified, and even if we believe that Trump’s supporters warrant it, if it’s not productive then sure we can condemn it, right? And while the zeroth question, the morality of violence, requires a moral consensus, and the first question is a matter of speculation, certainly people can see how this is going to go over, right?

In my view, they should be able to see it. The horror people feel may be pearl-clutching to some, but it’s pretty real. Overwhelmingly, people don’t want to see it. It’s bad optics. It feeds into Trump’s and Trumpers’ perceptions of Who The Enemy Is. It takes the worst things Trump has said about violence at his rallies and puts them in a grayer context.

But more than that, though, this is breaking a lot of eggs without so much as an omelette recipe. If violence can be justified along tactical lines, what is the plan really? Do Trumpers stop showing up to rallies, or do they start showing up armed? The best tactical argument I can think of is that eventually a Trumper will literally shoot somebody and it will make Trump look bad. I would be surprised if that’s what they want though. I believe they have convinced themselves that these conflicts hurt Trump, and I believe that’s wrong. If you’re going to try to bait them, try to bait them into hitting you. Don’t hit them to try to bait them into shooting you.

Though I suppose if you’re willing to do that, you pass the threshold of the first question.

During the primary, I advocated quite forcefully for denying Trump the nomination if he got a plurality, and even blowing everything up if he got a majority. My support for the latter ebbed once it started to look like he was doomed in the general because there was no need to wreck the process if the process would itself remove the threat. Playing convention games, though, isn’t advocating violence. The thresholds for the latter are significantly greater.

In our system, there are all sorts of intermediate measures to do our part to combat Trump, if you are inclined to want to. The lowest-threshold item is to simply vote against him, or you can vote for Hillary Clinton. You can also donate your time or money to seeing him defeated. You can register your opposition by holding out a protest sign outside of one of his rallies. You can write a blog. If it’s really dire, you can stop traffic or even damage property. There’s a spectrum with varying degrees of severity.

One seduction of violence is that it is a high-impact maneuver. Our vote is one upon a hundred millions or so and we have neither the time nor energy to have a substantial impact on a national level. Punch a guy, though, and your statement is heard across the world. People will know not only that Trump is opposed, but that you oppose him. I get the allure. But with the alternatives available, it raises questions about whether it’s about Trump or about you. That’s something to mull over, anyway.

Democracy, as they say, is the worst system except all others. One of the things that makes it less bad, though, is that it allows us a means to resolve issues without resorting to violence. There are scenarios where violence is the only way, but rarely is that true in a democracy. If it is true in a democracy, it involves drawing attention to a threat that people are unaware of. Whatever else we might say about Trump, people are aware of him.

This ties into the second factor: effectiveness If Trump is going to win the presidency, then you are likely emboldening the majority. If his is a minority, then democracy is there to handle that. And if it’s counterproductive, then literally doing nothing is more effective.

This is an interesting map, but it’s weird to say “People at the bottom range of income cannot afford the middle range in housing” and present that as an interesting finding.

This is an interesting map, but it’s weird to say “People at the bottom range of income cannot afford the middle range in housing” and present that as an interesting finding.

The pollster who calls you may know better than you who you’re going to vote for.

Wild energy ascendant! Of all renewables, I like wind energy the most because windfarms look cool (only oil refineries look cooler).

David Roberts looks at the persistent gender gap of nuclear power support. Turns out, it’s all about science science white male hierachical buzz buzz privilege male effect. Science!

I don’t really have an objection to this. Sometimes collisions aren’t actually accidents. Sometimes, they aren’t even negligent. A while back Jonathan McLeod pointed to a case where they used the A-word in a case that the article itself said, in the previous paragraph, was believed by police to be intentional.

Following up on the Thiel/Gawker story, Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry gives a French perspective, and Marc Randazza falls squarely on Thiel’s side.

Here’s a look at the fiscal solvency of our states.

Uhhh, I guess vapers will take support wherever we can find it?

Yes, this would be entirely welcome. At least we’ve got Mitt.

Good news! Venezuela is getting more organized! Wait, not good news at all…

Grady Smith argues that the tension between country music’s party-boy style and religion is doing both a disservice. I checked out of the contemporary country scene some time ago, but if the depiction is accurate it’s a shame. Many of the best religious songs I ever heard were country, and some of the best country songs religious.

I’ve seen the first 45 minutes of Frost/Nixon five times (movie day substitute teaching), though I’ve not yet seen the second half. I wondered why @dick_nixon objected to it so since I thought the characterization of Nixon was on the whole kind of affectionate. Turns out, I needed to see the second half.

A story of conversion to and from the LDS Church.

Paulette Perhach explains the F*** Off Fund.

Among early skeptics of the Hiroshima bombing was Dwight Eisenhower. In fact, it was conservatives who were critical of the Hiroshima bombing.

Going to create a new Twitter series: "Who's to Blame for the rise of Donald Trump?" …

— Justin Tiehen (@jttiehen) December 12, 2015

1. Angela Merkel? https://t.co/VScxaY6Yc5

— Justin Tiehen (@jttiehen) December 12, 2015

2. The PC Left? https://t.co/5Shy4bcCqY

— Justin Tiehen (@jttiehen) December 12, 2015

Monk fight! Monk fight!:

Which reminds me of this great Adam Carroll song, Bubble Gum or Bad Kharma: