Blog Archives

Can we use lasers to catch drunk drivers?

Can we use lasers to catch drunk drivers?

You may have seen a map of “74 school shootings since Newtown.” It’s… highly dubious. [More]

If democracy is the worst kind of government except all others, can we come up with a better one? io9 has twelve alternatives from science fiction.

We think of good dads mostly as being good for their sons, but they affect their daughters, too.

Single fatherhood is becoming more common, up from 1% in 1960 to 8% now, and from 14% of single-parent households to almost a quarter.

Only 3% of Swedes lead unhappy lives. Yet some people leave Sweden, though, and here’s why.

Amazon is relegating Hachette’s wears until or unless Hachette agrees to terms more favorable to Amazon. Commentary on the issue has almost all been sympathetic to Hachette. At the Guardian, Barry Eisler takes a different view.

Black markets on the web may lessen drug violence.

Non-complete clauses are becoming more common, and Alex Tabarrok argues this represents a threat to innovation.

Lorenzo lays out the case for small nations.

Bobby Jindal is virtually deregulating the sale of homemade foods!

Job licensing in service-oriented industry inflates wages by fifteen percent. Vox has a run-down. Interestingly, it’s more common in the South and West than the Northeast.

Cross Canadian Ragweed – Look At Me from Hartmut Braeunlich on Myspace.

It’s frustrating has heck that this video isn’t available on YouTube or anywhere else but MySpace, but here it is. It’s one of my favorites. Better done than a lot of their more professional videos. A great song, to boot.

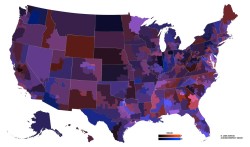

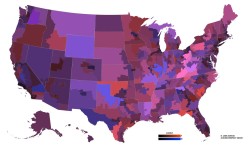

Luke DuBois has a large number of maps comparing men and women in various respects. The first map is loneliness and last map is the Virginity Map:

The loneliness map is about what I would expect it to be. In the male-heavy west, it’s more blue. In the woman-heavy east, it’s more red. The virginity map is more interesting. Less uniformly blue than I would expect, given what a lot of people in our corner of the ‘sphere say about such things. Less uniformly red than I would have guessed, given that it’s based on self-disclosure. It’s slightly more blue than red with some blue areas most notably along the border where there are presumably young men who came over alone. North Dakota and Alaska are pretty predictable. Wyoming was quite a surprise.

The liberal and conservative one was interesting, especially given the redness of the former.

Eastern Colorado women appear to be quite open about their craziness.

The least surprising? Women using the word “happy” a lot.

I’m really surprised that people are actually putting the word “virgin” on their profiles. It’s also weird that they would put the word “lonely.”

This is all, of course, rather unscientific. Especially the self-reporting aspect. I’m also less than entirely clear about the methodology used. But hey, maps are fun.

Matt Phillips explains that the use of personal checks has been in radical decline:

The usage of checks as a payment system has plummeted in the U.S. in recent years. In 2000, checks were used in more than 40 billion transactions, according to a recent report from the Federal Reserve’s Cash Products Office. That number is down to less than 20 billion, according to the Fed’s most recent numbers, which are based on a survey conducted in October 2012.

When it comes to American payment preferences, checks run a distant fourth. (At least when you measure the overall number of transactions. Checks are used for about 19 percent of the value of all purchases, slightly higher than debit or credit cards.) {…}

While the number of check payments continued to rise into the mid 1990s—they peaked at an estimated 49.5 billion in 1995—checks began to lose significant market share to alternative forms of payment like debit and credit cards and direct, electronic, automatic clearinghouse payments (ACH).

The trend toward electronic payments only gathered pace, and by 2003, the Fed estimated (pdf) that other forms of payment had overtaken checks in usage. And by 2006, checks accounted for barely one-third (pdf) of non-cash payments in the U.S.

This had more resonance for me several years ago than it does today. When I lived in Cascadia and Estacado, check-writing was more or less non-existent. When I had to write a check, it was actually a big ordeal because it meant that I would have to track down the checks, the envelopes, stamps, and so on. The infrequency of all of this meant that I didn’t have to be organized about where these things were. And I wasn’t.

That changed when we moved to Arapaho, where suddenly checks were required for just about everything. Neither the power company nor utility company accepted electronic payments. Nor did trash pick-up, though that was quarterly instead of monthly. Notably, the monthly charge for all of these things changed on a regular basis, so I couldn’t do the automatic payment system through the bank (where they essentially cut you a check). Strangely enough, I actually found this to be reasonably convenient. Once I was in the habit of writing checks, whether I was writing one or four didn’t really matter so much. With four, I could develop a system – mostly a matter of having a station for my check-writing stuff.

That continued when we moved out here, where once again neither the power company nor city utilities accept automatic payments.

Eventually, one would assume, all of these recipients will accept electronic payments. But prior to moving to Arapaho, I’d assumed that almost all of them had. The statistics about the relative decline in usage are a bit misleading, though. It’s not just that people are paying with credit cards and debit cards instead of checks, but they’re doing so instead of cash. Despite the fact that I currently write four checks a month (power, utilities, rent, storage), it’s a distinct minority of the non-cash payments I make, due mostly to a decline in cash payments in favor of plastic.

Has anyone been having pop-up ads or splash pages while visiting my site? I have not signed on with advertising partners. So if this is an issue, it’s not because I’m selling out! Let me know and I will try to get to the bottom of this.

Could the solution to distracted driving be something as simple as a cleaner typefont?

I think there’s a fair number of adjustments we could make to cut down on technology-based distracted driving. In some cases, we’re moving in the wrong direction. I don’t mean by having more and more devices that distract us. Rather, because we’re moving away from physical buttons and knobs, which are easier to manage without taking your eyes off the road for very long, to touchscreens which require more precision and, thus, more attention.

The biggest thing we can do, though, is really ramp up R&D on voice control. I have my smartphone set up so that it reads text messages to me as they come in. I’m not far from being able to reply with little more effort than changing a radio dial. But the last inches seem to be the hardest.

More to the point, though, I’ve had to “rig” my devices to do what I can do.

So hasn’t more effort been put into this? Well, a lot of effort has been. Especially by the carmakers themselves.

Studies have demonstrated that voice systems are actually a hazard in themselves:

What makes the use of these speech-to-text systems so risky is that they create a significant cognitive distraction, the researchers found. The brain is so taxed interacting with the system that, even with hands on the wheel and eyes on the road, the driver’s reaction time and ability to process what is happening on the road are impaired.

The research was led by David Strayer, a neuroscientist at the University of Utah who for two decades has applied the principles of attention science to driver behavior. His research has showed, for example, that talking on a phone while driving creates the same level of crash risk as someone with a 0.08 blood-alcohol level, the legal level for intoxication across the country.

The counterargument to this is that, well, people are going to have the technology anyway. Even if you ban them from the cars themselves. Would we rather they be using it trying to tap virtual screens on a small keyboard, or talking back and forth with the device? The latter is obviously the safer in the abstract.

The concern, then, would be that people who wouldn’t pick up a device will talk to the device. So leading to less danger on a per-user individual, but a higher collective hazard because more people are doing it. This is possible, though it starts to move closer to the territory of the argument against ecigarettes (the danger being in its comparative safety).

Keeping this technology out of the cars themselves won’t keep them off the phones that will be in the cars. Laws against texting and driving don’t work. Obama’s former TranSec Ray LaHood wanted to disable phones in cars, but that disables passenger phones as well as driver phones.

The underlying problem won’t really go away until the cars drive themselves.

A few weeks ago I wrote a post about the popular languages in the US. One of the surprises was that, after English and Spanish, the most popular language spoken was German. I wondered if it might be the descendants of German immigrants learning the language of their homeland or what. We don’t think of German immigrants as a particularly recent thing.

If only I read my own blog. I wrote a post in 2010 about German immigration into the United States. I quoted from an article:

Germans are leaving their country in record numbers but unlike previous waves of migrants who fled 19th century poverty or 1930s Nazi terror, these modern day refugees are trying to escape a new scourge — unemployment.

Flocking to places as far away as the United States, Canada and Australia as well as Norway, the Netherlands and Austria more than 150,000 Germans packed their bags and left in 2004 — the greatest exodus in any single year since the late 1940s.

High unemployment that lingers at levels of more than 20 percent in some parts of Germany and dim prospects for any improvement are the key factors behind the migration. In the 15 years since German unification more than 1.8 million Germans have left.

Anyhow, it’s not just a recent thing, but was more prominent in relatively recent history than I thought of. Pew points out that it’s Germans, as opposed to Italians or Irish like I might have guessed, who Mexican immigrants have displaced as our biggest source of immigration.

As you can see from the map, as recently as 1960 the Germans dominated the immigration landscape (to the extent that any country did), and in 1990 they were right up there with Mexicans.

At Salon, Kim Brooks wrote a piece about the fallout from having left her child in her car:

I took a deep breath. I looked at the clock. For the next four or five seconds, I did what it sometimes seems I’ve been doing every minute of every day since having children, a constant, never-ending risk-benefit analysis. I noted that it was a mild, overcast, 50-degree day. I noted how close the parking spot was to the front door, and that there were a few other cars nearby. I visualized how quickly, unencumbered by a tantrumming 4-year-old, I would be, running into the store, grabbing a pair of child headphones. And then I did something I’d never done before. I left him. I told him I’d be right back. I cracked the windows and child-locked the doors and double-clicked my keys so that the car alarm was set. And then I left him in the car for about five minutes.

He didn’t die. He wasn’t kidnapped or assaulted or forgotten or dragged across state lines by a carjacker. When I returned to the car, he was still playing his game, smiling, or more likely smirking at having gotten what he wanted from his spineless mama. I tossed the headphones onto the passenger seat and put the keys in the ignition. […]

We flew home. My husband was waiting for us beside the baggage claim with this terrible look on his face. “Call your mom,” he said.

I called her, and she was crying. When she’d arrived home from driving us to the airport, there was a police car in her driveway.

Multiple people on my Facebook timeline shared the article with a comment about never taking any chances. A part of me wonders if they even read the article, or how they might have missed the point so badly. Given the specifics of the situation, there was little or no threat from the weather, from thirst or starvation. The only threat was from the authorities themselves. The threat of a child losing his mother because of a culture that says “take no chances.”

Joseph Stromberg argues that spanking should be illegal:

Research, though, tells us that getting spanked as a child can leave a discernible mark on people: it makes people more likely to suffer from addiction, depression, and other mental health problems as adults. This is one reason why 37 countries have explicitly banned all physical punishment of children — even by parents — since 1979.

Even our own existing state laws generally define child abuse as “endangering a child’s physical or emotional health and development.” By this standard — and given what we’ve recently learned from research — any form of physical punishment violates children’s rights, whether it’s done by a teacher or parents.

Making something – like spanking, or leaving your children in a car, is not simply a matter of saying don’t do it. It doesn’t make it go away. Rather, it’s the initiation of a legal process that threatens to pull apart families. The question is not “Should parents spank their children?” but rather “Should we take children away from homes where they are spanked?” and “Should we send parents to prison who do this?” There is an extremely strong argument, in my view, that there lies the road to far more ruin than the initial offense. My answer to the above three is “no” which, in a legal framework, is inconsistent except to the extent that we believe we should allow people to do things we consider to be wrong. In a best case scenario, such laws would be enforced loosely or inconsistently. The former typically leading to the latter, which has its own problems.

Sayeth Michael Brendan Dougherty:

The novel phenomenon of American upper-middle-class helicopter-parenting, in which kids are scheduled, monitored, and supervised for their “enrichment” at all times, is now being enforced on others.

It’s an odd way to “help” a child who is unsupervised for five minutes to potentially inflict years of stress, hours of court appearances, and potential legal fees and fines on their parents. Children who experience discreet instances of suboptimal parenting aren’t always aided by threatening their parents with stiff, potentially family-jeopardizing legal penalties. The risk of five or even 10 minutes in a temperate, locked car while mom shops is still a lot better than years in group homes and foster systems.

It’s only a slippery slope to talk about such things if we’re talking about making laws that have comparatively little teeth.

Heebie-Geebie wrote on Unfogged:

I have a new theory: a contributing factor might be the rise of the horror-story-as-promotional-device. Did this happen much before, say, MADD? I’ve got it in my head that there’s been a shift from private grief and shameful let’s-never-talk-about-how-cousin-drowned-at-the-picnic to the current model, which is to channel your grief into transforming the world and making sure other parents don’t suffer through your hell. It’s basically a good thing – if your child dies due to complications from premature birth, and as part of your grieving process you become very involved in March of Dimes, then that is absolutely good and productive and so on.

But I wonder if the over-parenting vigilance isn’t partly due to the bombardment of individual stories of the child who was only out of sight for three minutes. Like Kahneman says, our brains are really terrible at statistics.

I wonder about a slightly different angle of interest to me. In What To Expect When No One’s Expecting, Jonathan Last explores the various disincentives of people to reproduce. Among them, he talks of the comparatively trivial example of car safety seats. The increased requirements of car safety seats adds a not-insignificant burden to people who want larger families. Every life saved is precious, of course, and it’s wonderful to save them, but requiring them longer and longer means more kids in them at the same time, which requires the expense not only of the seats but of bigger vehicles and more hassle. Making parenthood more expensive, more difficult and less flexible, have an effect on the number of children we choose to have.

A long while back I was in Queen City with Lain. I parked at a parking garage about a mile away. I had to go to the car to get something and took the baby. The problem was that I forgot to take the child seat. The threat to Lain’s life and livelihood on a one-mile drive is probably marginal*. The pain-in-the-ass of walking a full mile back and then forth again was definitely not marginal. One of the things I remember as I stood there on my car was not a fear that something would happen on that straight drive, but that I would get caught and arrested. My decision was made on the basis of the law.

One of the things Brooks talks about in her piece about leaving her son in the car is that in her conversations with people, a whole lot of parents admitted to having done what she did. Some suggested that all parents have. It’s certainly the case that a whole lot more parents have than have been arrested for it. Uncountably more times than a child has died or been hospitalized for it. But the instinctual response – one I have myself – when we hear about something going terribly wrong or getting arrested for it is a variation of putting your child at risk and the unacceptability of ever doing so.

As the article mentions, though, we do it every day. We just draw odd lines on where we should. When we fly, Lain gets her own seat even though one isn’t required until she is two. As a matter of safety, and sanity, we want to do that. Most parents don’t. A lot of people think that it should be legally required. Child safety, after all. But these things come at a material cost. Having to buy a third ticket can be the difference between a family going somewhere or not going somewhere. This matters. It can also be the difference between flying and the more dangerous – with or without a carseat – decision to drive.

There’s something in us that cringes when we see a child in an obvious – even if minute – danger. This is not a bad thing. If we keep it in check.

One of the other things that Last explores in his book is the increasing parental involvement over time.

Here’s where it gets interesting: From 1965 to 1985, mothers actually spent less time taking care of the kids (just 8.8 hours per week in 1975 and 9.3 hours per week in 1985) while fathers inched their numbers up a tiny bit, to 3 hours per week. After 1985, both moms and dads started doing more-lots more. By 2000, married fathersmore than doubled their time with the kids, clocking 6.5 hours a week.

Overall, American fathers have become more involved in raising their children. So much so that, as economist Bryan Caplan jokes, they could almost pass for ’60s-era mothers. But what’s really astounding is what mothers have done. By 2000, more than 60 percent of married mothers worked outside the home. In doing so, they increased their paid work hours per week from 6.0 in 1965 to 23.8. Yet even as they moved out of the house to pursue careers, they also increased the amount of time they spend with their children, cranking it up to a bracing 12.6 hours per week.

Now, on the one hand, this is a happy development. It’s a good thing to have parents taking a more active role in their kids’ lives. But on the other hand, these numbers explain why parents are so frayed and stressed these days: Because however nice it is to be spending more time with your children, it’s also a rising cost. There are only 24 hours a day and if people are spending more time on kids, those hours have to come from somewhere.

The rising expectations of parenthood go beyond money and into rising standards for pretty much everything. Babysitters are not typically required to be licensed and bonded, but I wonder if we’re not too far away from that. There is a lot of movement to make daycare more regulated, and thus more expensive. Which is a mixed bag. Setting aside statutory requirements, though, the pressure parents put on themselves and one another for the right daycare can be quite intense. It sends a message of rising expectation that says “It’s better not to have children if you can’t…” with the sentence ending with an ever-increasing list of demands. It’s a message that arguably resonates most with the greatest tendency towards being responsible. The irresponsible either ignoring the demands, not particularly intending to be parents, or just not thinking that far ahead.

Increased spending on children is typically lauded. It’s more of a mixed bag when we talk about the time we devote to them, however. Almost always, though, we seem to talk about it being a good thing or a bad thing from the child’s point of view. Increased parental requirements to help kids with their homework becomes a statement about how much pressure kids are under. Helicopter parenting, when criticized, is frequently targeted on how it affects children. I used to wonder if this was a rationalization so that parents could give themselves a break. A part of me actually hopes that is the case, because that is important. But whether it’s a rationalization or whether it truly is all about them, it’s difficult to talk about it in any other way.

The cumulative effect of all of this being a level of responsibility that can be off-putting to a lot of people. Which, people who don’t want kids shouldn’t have them. Pushing the level of responsibility ever-higher, though, can have the effect of making people not want children. Putting a chasm between “parenthood” and “not parenthood” that makes the latter more attractive. Not because of car seats, in particular, or restrictions on leaving your kids in the car in even the most benign circumstances, or the increased investment parents are supposed to make, but the aggregate effect of all of these things and more.

In Michael Connelly’s A Darkness More Than Night, Terry McCaleb says that being a father is like having a gun always pointed at your head. Rationale being the knowledge that if anything happened to your child – if you could have prevented it, anyway – you wouldn’t be able to live with yourself. I feel that very keenly. I also feel, though, that driving yourself into insanity is its own problem. I don’t object to all safety laws, by any stretch of the imagination. I don’t favor needless endangerment. I do favor, though, a degree of sanity. For the kids, but also for the parents.

* – The particular issue being her very young age. Even if a time and place with less restrictive child seat requirements, it would be at best logistically challenging and at worst there would be some definite safety concerns insofar as the number of bad things that could happen in even a minor dust-up. The comparative lack of danger coming, primarily, from the fact that it was a short trip. Nothing, really, in this post should be construed as an endorsement of the notion that babies should not go into car seats or that there shouldn’t be laws to that effect.

I don’t understand a word in this song, but it’s a pretty awesome music video.

I actually saw it without hearing it. We were eating at a Mediterranean restaurant and it was playing as part of a loop on the TV. Along with what appeared to be random videos of southern Europe (maybe narrated, no audio). The music is okay, and in French. But it definitely caught my attention and is now on the master playlist at home. (The master playlist being about 300 or so music videos I play when I need to keep Lain occupied.

As most of you know, Seattle has raised its minimum wage to $15/hr. It follows the airport town of SeaTac doing the same, and has made more tangible the federal government’s to raise it to roughly ten dollars an hour by making it seem more modest.

The minimum wage has become a battlefront on the subject of inequality. Even some who support raising the minimum wage to $10 are more skeptical of the higher figure. Even inequality guru Thomas Piketty is concerned.

One of the advantages of having our decentralized systems is that I can eagerly await the results – whatever they are – without having to face any negative consequences if it does turn out to be a bad idea. I feel the same way about Vermont’s flirtations with single-payer.

The other advantage to having a decentralized system is that it can take advantage of what being a good idea in one place can be done there, but other places don’t have to follow suit. If we’re going to try an extremely high minimum wage somewhere in the country, Seattle is actually a pretty good candidate. The high cost of living makes a $15 minimum wage easier to justify than in a city like Boise or Denver. It also has a booming economy, lots of money, and a lot unemployment rate.

Further, Seattle is actually not all that large. It’s city population is above Nashville but below El Paso and Forth Worth. What we think of as “Seattle” is actually a clump of cities. But the minimum wage hike will only apply to Seattle. This could be good if it allows some of the low-wage amenities to exist just beyond city limits but still be accessible to the city’s population. It could be a bad thing if it drives out some jobs. Since Seattle is expensive, though, and more expensive than most of the area that surrounds it, it could make it harder to discern overall effects.

If things go well in Seattle, or are assumed to, we should be wary about talking about rolling it out nation-wide or using it as a justification to angle a national minimum wage towards $12 or something. But if successful in Seattle, then it’s definitely something that similar cities like San Francisco and New York should (and undoubtedly would) look at. These places are far more expensive to live in, and given those employers that are still there are so despite increased costs, it could be that there is quite a bit of inelasticity involved.

Dave Schuler’s concerns, though, are probably pretty well-founded:

I can believe that a $15 minimum wage in Seattle where the unemployment rate is 5.3% can be absorbed by the local economy. Seattle’s local minimum wages incentivizes politicians in Chicago where the unemployment rate is 10.6% to push for our own $15 minimum wage and here it might well throw people out of work or make it harder for them to find work. Not to mention driving businesses on which the poor depend out of the city or even out of the state.

Chicago politicians can always deny responsibility on a “hoocoodanode” basis.