Category Archives: Market

A few weeks ago I wrote about corporations and politics, using the NRA boycott as an example of how the left is learning to make peace with using economic muscle to get what it wants. They’ve also done a good job of framing it as markets at work. I would argue that maybe this is one of those cases that capitalism and markets diverge, and that this may be more of the former than the later. At the least, I think there was something else going on:

A lot of people made it seem like capitalism and markets, and while there was some of that there was something else going on: The people who made those decisions were sympathetic. Delta didn’t run thorough cost-benefit analyses. They didn’t do market research on which paths would have helped and hurt them. They made their decisions quickly. Corporations are made of people, and people make the decisions. Delta and FedEx had pretty similar sets of incentives. One made one decision, one made the other. Increasingly, though, the people in important corporate positions are sympathetic to the social causes of the left. As they have burned all of the bridges from their island to the mainland, this is going to be an increasing problem for the right. But for the left, it’s a windfall.

The pushback I get from this is that corporations make decisions based on money and therefore if they made this choice, it was about money. What that misses is situation likes this, where you’re dealing with a lot of ambiguity. You don’t have time for market-testing. It’s hard to even say what appropriate market testing would even look like. What’s the A-B test here? So in the absence of a clear indication of what to do, decisionmakers are going to follow their instincts. Their instincts are colored by their worldview and their social environments.

In other words, I think the decisionmaking looked like this:

You have to work really, really hard to try to fit the CEO complaining about getting the stinkeye into the “markets at work” paradigm. Further, this is where cultural influence matters a great deal. Whose criticism is Harding worried about? What do those people think? Assuming no successful boycott, one of them is probably worth ten of the kinds of people he doesn’t otherwise associate with.Peter Harding doesn’t look like the bad guy. He doesn’t resemble the villain who is responsible for putting mountains of sugar into fizzy drinks and turning the country’s youngsters into a generation of fatties.

But that’s how Harding, who runs Lucozade Ribena Suntory – the UK soft drinks business owned by Japan’s drinks giant, Suntory – was made to feel by everybody from Jamie Oliver to health campaigners and the media.

“I was being stared at, at the school gates by other parents. Jamie Oliver was beating me up, so were other celebrities, NGOs and the media. They were demonising me as though sugar were the new tobacco. The criticism was not nice for anyone, including our employees.”

When conservatives retreated to Fox News and away from the media (entertainment and news) and act as renegades against academia, this is what they gave up. Going forward, the people who make the decisions are likely not to be in their corner, from a social or instinct standpoint. That matters a lot! When there were clear business considerations, a number of companies actually didn’t cut ties with the NRA. Google, Roku, Apple, and Amazon all stopped short of letting it interfere with their actual business plans, and Dick’s Sporting Goods appears to be the only one willing to pay a price. It was only when a decision favored dropping the NRA or it was ambiguous. And given how quickly everything moved, it was usually ambiguous.

In this case I strongly suspect that this was not a good business decision. To argue that it is requires more heavy lifting than can be done. To me, whether this was the right decision or the wrong one depends on how it tastes, but it was clearly a decision based on the moral intuitions and social circumstances of the decision-makers. And in that, it wasn’t alone.

Dr. X, a friend of Hitcoffee, has warned against what some mental health professionals call the Dark Triad. This triad is, to quote Dr. X, a “personality organization that comprises three psychological traits: psychopathy, narcissism and Machiavellianism.” People with that personality organization are dangerous. They are a problem that needs to be dealt with, especially if they are a coworker or in a position of responsibility.

What do we do with such people? In the comment thread to that post, Dr. X suggests that we fire them. To me, the obligation to fire implies that we shouldn’t hire in the first place. If the dark triadic person is not independently wealthy and yet can’t or shouldn’t be hired, how should he or she fend for themselves? Perhaps once properly identified–either through that person’s actions or through some sort of deep analysis–then we ought to consider civil commitment, or prison if justified. Or you can do the Philip K. Dick option: hunt down the androids and eliminate them. I reject that “solution” as does Dr. X and most (all?) others I”ve heard speak on it. But the terms of the discussion are consistent with certain conclusions.

Absent in the discussion on that thread and in the material Dr. X cites (or at least in the quoted portions of that material…I didn’t read the linked-to articles), is a discussion of whether this personality organization is just how or what someone is, or if it has a (personal) history. If people develop into that organization or develop out of it. Not to call this an illness–it’s not clear to me that the language of “personality organization” is a language about illness–but…is there a cure? Or are people just like that?

I’m obviously uncomfortable with the idea. Maybe it’s naivete or wishful thinking. If such people exist, then they exist whether I like it or not. If almost by definition such people don’t seek to change or improve or grow, then they don’t. Sometimes survival and defense of the common good are important. My wish that such people who would imperil either don’t exist doesn’t mean that they don’t.

These discussions remind me of the “mark of Cain” from Genesis. I thought it would be cool to incorporate an allusion to that story when talking about such people. But then I actually read the story, probably for the first time since I was a child. The story starts out as I remember. Cain kills Abel out of jealousy or envy or whatever. The Lord punishes him: “When you till the ground, it shall no longer yield its strength to you. A fugitive and a vagabond you shall be on the earth”

But it doesn’t end there. Cain complains that it “will happen that anyone who finds me will kill me.” To that the Lord commands that “whoever kills Cain, vengeance shall be taken on him sevenfold.” And he sets a “mark” on Cain to warn people not to harm him.

I’m no expert in Biblical interpretations, and I imagine that that passage has been interpreted and reinterpreted through the ages. There’s also a point of unclarity. The referent “him” on whom vengeance is to be meted sevenfold strikes me as amphibolous, at least in the version I’m quoting: I assume the vengeance is to be meted against the one who would harm Cain, but perhaps Cain is the recipient of the vengeance?

Still, the “mark” of Cain seems on my uninformed reading to be the opposite of what I had thought. It strikes me as a mark of mercy, or perhaps mercy tempered by a warning. People are not expressly forbidden to be wary of him or to stop him from further crimes, but they are forbidden to harm him.

Again, there may be other ways to interpret that story, and one might legitimately question whether that story ought to be a guide to anything. But that story exists and I can’t shake it, just like I can’t shake the possibility that dark triadic persons exist.

Last week I posted an Linkage Over There about a superbowl Audi ad:

Well, if you’ve been reading along, I think you’ve figured out what the real message of this Audi advertisement is, but just in case you’ve been napping I will spell it out for you: Money and breeding always beat poor white trash. Those other kids in the race, from the overweight boys to the hick who actually had an American flag helmet to the stripper-glitter girl? They never had a chance. They’re losers and they always will be, just like their loser parents. Audi is the choice of the winners in today’s economy, the smooth talkers who say all the right things in all the right meetings and are promoted up the chain because they are tall (yes, that makes a difference) and handsome without being overly masculine or threatening-looking.

At the end of this race, it’s left to the Morlocks to clean the place up and pack the derby cars into their trashy pickup trucks, while the beautiful people stride off into the California sun, the natural and carefree winners of life’s lottery. Audi is explicitly suggesting that choosing their product will identify you as one of the chosen few. I find it personally offensive. As an owner of one of the first 2009-model-year Audi S5s to set tire on American soil, yet also as an ugly, ill-favored child who endured a scrappy Midwestern upbringing, I find it much easier to identify with the angry-faced fat kids in their home-built specials or the boy with the Captain America helmet.

While some dismissed this characterization, I thought it was rather spot-on. If this were a Chevy or a Nissan ad, I might think that some of the characterizations are happenstance, but this is an Audi ad. That means class is not incidental, but rather core, to the product. So we can likely assume anything involving class in the ad is likely intentional. And in this case, it did so in a rather politically skewed direction.

This ad was clearly conceived when it looked like Hillary Clinton was going to be the first female president. And in the run-up to the ad, Audi did a publicity blitz about its commitment to gender equality (hehe, hehe). It was aimed squarely at a particular segment of its clientele. But before we get too much into that, let’s talk about wine and cheese. For a few months, my Twitter feed contained this ad:

2 MIT grads create a wine club to match you with wine. Take the Wine Quiz & see your matches https://t.co/goeuWOSs3P pic.twitter.com/EY8yPCGu48

— Maria Santacaterina (@mcsantacaterina) November 13, 2015

There is some really intense social and class signaling going on in that ad. I mean, let’s count the ways: Name-checking the most exclusive university in the country, science!, whiteboard with code, Apple computer, elegant geek girl. It really has it all and it just screams New White Collar through and through. Which, if they’re selling a cultural service like wine, is a pretty good pitch! They know their likely audience. Being close to that audience myself, I actually think it’s pretty well done. Maybe a bit overkill, but I only have one foot in that pond.

Now, the Audi ad goes for a slightly different set. Older and wealthier. More likely for their to be a family involved. As the article says, the protagonist isn’t the girl so much as the dad. The dad with the girl to be proud of. The dad who is on the Right Side of History. The dad who doesn’t need an Audi to be good, but is good and Audi is good and let’s get together. The characterization of The Other is probably a necessary component to that because goodness needs something to be compared to. Something a little grubby and unclean. The ad, as a whole, makes its pitch by equating vanity for virtue. It’s not toxic to conservatives, but to the extent that it appeals to conservative it’s going to be the squishes, the #NeverTrump sort, and those whose sensibilities align with left at least in terms of cultural cues.

Now, lest anybody think I am wanting to pick on one side, it’s not hard to come up with an idea of something similar aimed at conservatives would look like. Even if we’re looking an ad seeking to confuse vanity and virtue – or is it vulgarity and virtue – for the well-to-do right. We don’t even need to leave the auto market. Or the luxury auto market. Or the Superbowl.

A visceral yell. A combination of individualism and group (patriotic so it’s okay) achievement. My accomplishments are mine, your accomplishments are ours. It speaks to some less savory impulses in the same way the Audi ad does. Get this because you’ve earned it. Hard work! While the Audi focuses on a degree of innate you-are-evolved goodness, this one focuses on work and achievement. Which sounds good, if you kind of glide past the part where his achievements are his and others’ achievements are ours. But go America! This struck a positive chord with the people it was meant to, and a negative chord for others.

But just as you know the dad in the Audi ad didn’t vote for Trump, you’re pretty sure this guy did. This guy is, more or less, what I think of when I pass by the house of the guy that had the Trump flag in his yard. Really nice house. Obviously, the person was well off. Given that they put a flag in their yard, along with a Gadsden, suggests that he probably supported Trump throughout. That house has (surprise surprise) a full-size pickup in the driveway. Which is kind of on the opposite end of the spectrum as the electric car this guy is pitching.

Which is actually sort of the point. If the Audi ad is telling a well-to-do liberal that it’s okay to have a car that only rich people can afford because you’re good, this ad was telling future Trumpers that it’s okay to have an electric car because it indicates hard work and you work hard because you’re an American.

But, bygones!

I mostly got it because their children’s programming is supposed to be pretty good. I haven’t poked around too much, but it… doesn’t seem bad, at least. So maybe we’ll have it for a while and then we won’t. Lain has learned to load up and watch videos on the tablet, which is a mixed blessing. The idea of Netflix occurred to me when we were watching an Amazon Prime video on phonics. YouTube also has a good app for kids.

It’s just amazing how much stuff there is out there.

Despite the above-mentioned bad experience, I am genuinely impressed by Netflix the corporation. One thing in particular jumps out at me, which is that they pivoted really quickly to streaming video and did so before they had to. A lot of the time when a company gets the sort of market position that Netflix does, the tendency is to sit on it until someone innovates around you. In this case, they made the determination pretty early that streaming was the future and basically retired their own business model.

Anyway, with football season over I was able to scale back on our satellite service and still come out way ahead.

Back home, there used to be a bank that I’ll call GoUSA Federal Bank. It was a pretty big operation that existed locally but not really nationally. They were really everywhere, which was a big plus back when using ATMs was a regular part of banking. They also had really low minimum balances, free checking, and you could pick your own credit card design, which at the time was novel. Options were limited, but you could get a US flag, your state flag, or an eagle. Impressive stuff.

It was the ubiquity of their ATMs that had my interest, because my own bank had four in the entire city of Colosse, the nearest a half-hour from the Southern Tech campus. So I figured that I would get an account with them. But when I brought this up with people who had an account with them, they uniformly warned me against it. GoUSA was terrible, they explained. They had an incredible number of ridiculous surcharges and little in the way of monitoring. So you could use your debit card as much as you wanted, but if you passed $100 a month, you’d get hit with a $35(!!!!) penalty. And you had no way of knowing how much you’d used it.

Still, nobody switched away from them or anything radical like that. Their ATMs were all over the place. Plus, a credit card with an American flag on it.

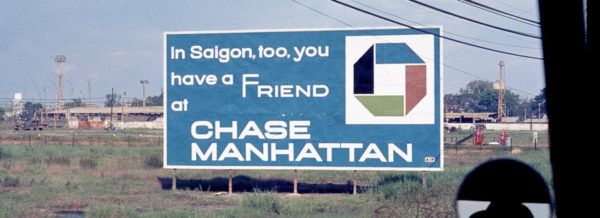

Photo by epicharmus

Manhattan? Manhattan.

If there was a way to emphasize that they were a far away entity with little interest in the local more effective than that, I cannot imagine what it would be. I mean, even California something-or-other wouldn’t have been great, but Manhattan was New York and (at least back then, pre-9/11 and all that) it was our duty really to just hate on New York. And so here come these yankees buying off our beloved little ragtag band of thieves bank and probably laughing at us and thinking they’re better than us.

Oh, and they also got rid of the customized credit cards. Now, instead of having the good ole star-spangled banner, they had… the New York Skyline. Because of course they did.

My then-girlfriend Julia’s family banked with them and I remember being in the room when he was on hold with customer support wanting to get his new credit card changed out for one with an American Flag on it.

It blew over after a while. Julia’s family did change banks. Bank of America did a big push at around that time and before I knew it, just about everyone was using them. I honestly don’t know how much of this was related to the Manhattan thing, except that BoA went to great pains to mention that they were from Charlotte at every opportunity.

Except me, of course. I stuck with my old crappy bank which at least would never have the word “Manhattan” associated with it. (A few years ago, they were bought out by BBVA, more formally known as Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria).

Some terms have a technical meaning and a common meaning, and the common meaning has a “normative slant.” The technicians know how to use the terms in the technical sense. But sometimes the common meaning slips in, in such a way that using the term ends up making two arguments with one word.

If one isn’t careful, using such terms can lead to confusion. Who’s to blame is not always clear. It could be the technician who uses the term or it could be interlocutor who misinterprets or misidentifies the technical meaning.

I have a list of three terms here, in ascending order of how knowledgeable I am about the technical definitions.

THE TERMS.

Marginal.

Title(s) of technicians. Economist; political scientist.

Technical meaning. The extra amount one is willing to spend to get the next widget. Or, somewhat less technically but still bound up with what technicians mean: the amount of change a given policy will bring about in a given direction.

Common meaning. An amount that is unimportant or trivial.

Normative slant to the common meaning. Mostly neutral, but it can swing either way depending on whether “amount” in question is good or bad.

Possibilities for confusion. When people speak of changes “on the margins” or assert that such and such policy will bring about “marginal” changes, they may have in mind the technical meaning. But sometimes they let slip in or leave unaddressed the common meaning. If it’s a somewhat harmful, but in his/her opinion necessary thing technician is advocating, he/she leave themselves open to the charge that he/she is minimizing the harm.

Sometimes, too: The size of the margin–not whether a marginal change will be brought about–is really what is under dispute. Simply pointing out that change (for the better or worse) will occur along some margin does not 1) demonstrate how much the change will be and 2) whether the change is worth it.

Exploitation (Marxist version).

Title(s) of technician(s). Marxist theorist; activist.

Technical meaning. Expropriating the surplus value of a worker to pay the profits of the person to whom the worker sells his or her labor. (Other technicians may have other meaning, but I’m focusing on the Marxist version.)

Common meaning. Somehow compelling someone to do something that they don’t want to do and that harms them.

Normative slant to the common meaning. Bad.

Possibilities for confusion. One sometime activist I knew who was steeped in Marxist theory often used the word “exploitation” to great emotional effect when describing the treatment of workers and the need for a revolution. And yet if you bring up examples of workers being treated well or workers as a whole benefiting from the prevailing economic system, then that same Marxist will fall back on the more technical meaning of “exploitation” and explain what they really meant was that the workers’ surplus value, etc., etc.

Historical.

Title(s) of technician(s). Historian.

Technical meaning. Representing the phenomenon of change over time. I believe it can represent persistence over time as well. The key point is that change happens (or doesn’t) but it can be explained by people’s decisions or by contingent, unforeseen happenings. This is probably a modern conceit. Historians in earlier times sometimes appealed notions of “forces of history” or “cycles of history” or “spirits of history” (e.g., Zeitgeist, Volksgeist, Ortgeist). I’m not saying my definition is true for all times and places and people, just that it’s the prevailing definition among those who were trained professionally in history and abide by professional history’s norms.

Common meaning. True and factual story of what happened.

Normative slant to the common meaning. Good.

Possibilities for confusion.There are at least two ways we sometimes commingle the technical and common meanings. One is simply using the common meaning when it suits us and then relying on our status (such as it is) of “historian” to claim that it’s truth.

The second is to speak as if merely demonstrating that a given belief or position or attitude is “ahistorical” we have therefore invalidated it. This is wrong, or at least “confusing,” because it assumes that historicality is the only measure by which to judge things. It judges people by the standards of professional historians even if those people did not claim to be abiding by those standards in the first place.

CONCLUSION.

Apologies.

There’s a lot I don’t know about the above terms. I’m least confident with “marginal.” Not being an economist or trained in economics, I suspect I’ve got it wrong on some level. So please correct me.

I feel a little bit more confident about “exploitation” and Marxism. But to be clear I’ve never read Marx to any significant degree, and most of what I “know” comes from reading Marxist-inspired historians and talking with people like my sometime activist acquaintance. And perhaps the “confusion” I talk about is just an anecdatum from my activist acquaintance.

Even with “historical” I might be off despite my training. In my anecdotal observation and experience, historians aren’t usually trained in grad school to examine the assumptions of history. Instead, grad school socializes them into the norms of the profession, and among those norms are the assumptions I mention above. My experience is no exception: I’ve given these assumptions some thought, but haven’t really investigated them systematically.

Envoi.

My takeaway, though, stands. We should beware how we use technical terms. It’s not only that there’s room for confusion, there’s also room for deception or at least lazy argumentation. And while the blame can’t always rest with the technicians, it sometimes can.

John Winthrop believed inequality is a problem. In 1630, on board the ship Arbella, he made the case in the sermon “Model of Christian Charity.” Whatever one thinks of his purported explanation for why inequality exists or of his ideas for coping with the problem, he warns that the problem is real.

God, Winthrop says, has “so disposed of the condition of mankind, as in all times some must be rich, some poor, some high and eminent in power and dignity; others mean and in submission.” Among the reasons Winthrop cites:

[God] might have the more occasion to manifest the work of his Spirit: first upon the wicked in moderating and restraining them, so that the rich and mighty should not eat up the poor, nor the poor and despised rise up against and shake off their yoke. Secondly, in the regenerate, in exercising His graces in them, as in the great ones, their love, mercy, gentleness, temperance etc., and in the poor and inferior sort, their faith, patience, obedience etc.

That’s only one part of the sermon, but I’m going to dwell on it. I read it as saying social inequalities are justified because they’re “God’s will.”

But justified or not, inequality is a problem, Winthrop seems to also be saying. Whatever good he can see coming from inequality, its existence is a warning as well as a opportunity for providence to do what providence does. The rich could eat up the poor. The poor could rise up against the rich.

Our sensibilities here are not necessarily what we might think they are. About the poor rising up to “shake off their yoke,” we probably entertain the possibility that the uprising is or can be a good thing. Or we might be quick to point out that what Winthrop might call “rising up” is more an assertion of rights, or an attempt to survive, than anything nefarious. Still, I don’t know how far most of us would go to endorse the uprising or the collateral damage that might ensue.

To make it more personal, I’d resent it if someone mugged me even if I grant they did so only because they really needed the money or because they are a bread thief. Not that all redistribution or “rising up” is comparable to a mugging. But if ending someone else’s poverty requires me to surrender even a small portion of my wealth or occasions an inconvenience to me of some sort, and even if I agree that the redistribution is right and just, it can still hurt in the short term. (For what it’s worth, a goodly amount of so-called “liberal” reform in the US usually sold on the claim that only the very rich will be inconvenienced. See Obama’s 2008 promise to raise taxes only on those who earn more than $250,000.)

Most of us probably agree that the rich eating up the poor is a bad thing, for certain values of “eating.” (I don’t really want to do it, but (sigh) I guess I have to offer this link.) But I’m not so sure we don’t do it. Most of us who adhere to a given political orientation–liberal, conservative, libertarian, for example–concur that feeding off the poor is bad. We may differ in assessing how the poor are fed off of, who is to blame, and how to end the feeding. But most of them–most of us–at least claim to agree that it’s bad.

Still, we’ve got ours and intend to keep it. Very few of us are going to engage in a life dedicated to fixing those things. Even fewer will withdraw from society to avoid all complicity in the feeding, not that such withdrawal would be easy or helpful. Maybe we can endorse a “first do no harm” strategy: don’t actively do anything to make things worse but try to fix things when we can and when it’s convenient. That’s probably the best we can hope for unless we want to be (non-fallen) angels, and I don’t want to be an angel.

But, you might object, Winthrop’s inequality is a zero sum game. It ignores that we can increase the size of the pie so everybody gets more even if some get even more than others. You might be right. I for one am a bigger believer than I used to be that material wealth can be increased for all and that we should pause before assuming the fact of inequality is automatically a problem. The “inequality symposium” Over There a few years ago drove that point home for me. And maybe material wealth is conducive to moral or humanitarian or spiritual (or whatever you want to call it). Such seems to be one of Deirdre McCloskey’s arguments in Bourgeois Virtues. (I think. I’m only 100 pages into and am a bit unclear on what exactly she’s arguing.)

While important, that objection doesn’t address Winthrop’s point. As long as there’s inequality, some will have more than others. Those who lack will be tempted to envy and to deny the humanity of those who have. How often have I heard of a real hardship suffered by someone much better off than me and yet mocked the person because after all, they had more? I don’ t know, but I can think of at least one example (the context is a discussion of Anne Romney’s convention speech in 2012 where she disclosed she suffered from MS and had suffered from breast cancer.)

Those who have will be tempted to abuse their gifts against their weaker or less provisioned neighbors. As someone who enjoys almost the full complement of special advantages (formerly known as “privileges”) that make living in this country so much easier, I have doubtlessly engaged in enough careless or casual cruelty toward others who do not share my good fortune. If I chose to bore you with specific examples, they would probably just sound like good old fashioned white liberal guilt. Nevertheless, it’s true.

I was going to end with an admonition to question our own envy against those who have what we lack and to exercise restraint and compassion when dealing with those who lack what we have. Noble sentiments. But I suppose most people hold them anyway and my harangues probably just sound preachy.

I’ll leave you instead with this. Less inequality is probably better than more if only because it tempers the temptations to vengeance and casual cruelty. But I suspect we can never end it altogether, and I’m not sure we ought to if we could. And I agree with Wintrhop. It is a real problem.

Megan McArdle gets at what bothers me about attempts to move toward a “cashless” society. For all the advantages of going cashless, she says, a fully cashless society gives too much power to the government.

Consider the online gamblers who lost their money in overseas operations when the government froze their accounts. Now, what they were doing was indisputably illegal in these here United States, and I am not claiming that they were somehow deeply wronged. But consider how immense the power that was conferred upon the government by the electronic payments system; at a word, your money could simply vanish.

Now consider what might happen if the government made a mistake. When I was just starting out as a journalist, the State of New York swooped down and seized all the money out of one of my bank accounts. It turned out — much later, after a series of telephone calls — that they had lost my tax return for the year that I had resided in both Illinois and New York, discovered income on my federal tax return that had not appeared on my New York State tax return, sent some letters to that effect to an old address I hadn’t lived at for some time, and neatly lifted all the money out of my bank. It took months to get it back.

I didn’t starve, merely fretted. In our world of cash, friends and family can help out someone in a situation like that. In a cashless society, the government might intercept any transaction in which someone tried to lend money to the accused.

She’s not saying necessarily that we shouldn’t go cashless, just that we need to decide how to face this new power that cashlessness gives to the state.

I agree.

In 1984, the narrator mentions screens that enable the government to observe citizens in their own homes. Citizens were not permitted to turn these screens off. For quite a while I’ve seen a correlation between these surveillance screens and internet access, cell phones, and now i-phone technology, the main difference being that we choose to use them. We can turn them off, and we do, but we depend on them nevertheless.

These devices make us “observable” to others, not necessarily or only to the state, but in a way that potentially guides our actions and maybe even the way we think.

We buy things online. Most of those purchases are in principle more traceable than cash purchases and perhaps even more traceable than purchases by check. At any rate, Amazon seems to know what I might be interested when I log on. Our search terms are (or so I hear) somehow remembered by my Google and contribute to what comes up when we search. When I go to weather dot com, the site knows I live in or around Big City. I assume that it would be fairly easy to track down my real identity from the blogs I comment and write on, or at least narrow the identity to my apartment building. Even dumber technologies like my flip phone track my phone calls and messages and my time zone.

And this is mostly beneficial to me. All this connectivity is entertainment, shopping, and a way to express myself and talk with people online I would probably never get a chance to meet in real life. I’m part of online communities where in my own way I have a voice and an opportunity to speak my mind and learn from others. I have and use a Roku, which streams channels from the ‘net. I listen to music on YouTube.

This is all mostly voluntary. I choose to turn on my computer first thing when I get home. The computer remains on until I go to bed, even if I’m not using it.

Still, I can’t shake the thought that I’m patched into a world where I and my choices are observed or at least observable.

I don’t think I’m paranoid. If I were, I wouldn’t use the computer at all. Or I’d use it less often. Or I’d take greater precautions than I do to protect my anonymity. I don’t think government bureaucrats are monitoring my to’ing’s and fro’ing’s on the internet. I am wary of identity theft, but not that wary.

As I see it, I’m taking two gambles. The first is that my life and views are so uninteresting and so non-influential and enough on the mainstream that no one (I hope) sees any special need to track me down. The second gamble is that there are a lot of fish in the pond for identity thieves, and I hope the chances of me getting my identity stolen is lessened by some sort of law of numbers, in addition to sensible precautions I can take myself.

Above, I compared this situation with Orwell’s 1984. It’s not entirely a good comparison. I’m not arguing that being “observable” is totalitarianism. I’m not even arguing that being observable is the same thing as being observed. In some ways, by being more exposed and more “visible” to the online world, I enjoy greater privacy than people did before such things existed. I probably enjoy more privacy on the web in 2015 than I would, say, in a stereotypical small town or closed neighborhood or enclave where everyone knows everyone else’s business.

But there’s also something not quite voluntary about it even though I choose it freely. It makes me uneasy.

I’m slowly resigning myself to the end of my Reebok shoes. It’s a hard process, but the sides are coming undone and part of the heel just came off. My endpoint for even my most favorite shoes come when I can’t walk in a puddle anymore. If we’re not at this point, we’re pretty close to it.

I’ve had these shoes since high school. In all the years since, I have never found any shoes this comfortable, despite the fact that these shoes are a size smaller (14) than I usually wear (15). They just… fit. Always have. They’re middle hightops, which I like because they give me a bit of ankle support. But the tops are low enough that I can just slip them on without having to go through the whole tying routine.

It’s hard to find any shoes that fit, though thankfully not as hard as it used to be. When I was young, Mom would take me to the shoe store and say “You can pick anything under $40” and that was cool because there was almost always something to pick. As my feet got larger, the selection got smaller. When I reached size 13, it became a matter of entering the shoe store and saying “What do you have in size 13?” and there would be a few options. Oddly enough, things improved by the time they reached 14, because stores were suddenly trying to serve the podiatrically endowed. The bubble burst at some point, and most places stopped offering shoes in sizes above 13. I can get by on some 14s, but 13s are just a no-go. So I would have to scour the countryside in search for the exception to the size 13 rule.

Until the Internet. God bless the Internet.

But what Zappos has yet to provide are shoes anything like the ones I am about to have to retire. Hightops have gone out of fashion. This is especially true for the larger sizes because the market that exists, exists for young people. The only hightops I have found are, of all things, sk8r shoes. They’re at least comfortable, though they require all of that tying business and cannot just be slipped on.

This is more of an issue than it used to be, because Lain. I used to be rather particular about my footwear. I wore steel-toed boots for the longest time. That stopped at some point after Lain became my charge. The ability to easy take shoes off and put them on became more important. I wear sandals a lot, which I used to almost never do. But sandals aren’t good in the winter time. You know what are? The Reebocks.

I’m probably going to have to give up on having high tops, which I’m prepared to do. The last non-hightops I got were pretty uncomfortable. Unfortunately, not uncomfortable in the way that you put them on and say “These are not for me” and return them. But rather, uncomfortable in the way that they are fine until you try to use them by walking around for part of a day. You think you’re just breaking them in, but they break you instead.