Category Archives: Statehouse

Recently in the headlines is the GOP dissatisfaction with the CNBC debate. What’s a little unusual about this is that almost everybody agrees that the debates were poorly done. To pick one example, Tod Kelly says:

The worst part wasn’t that their questions were often insipid. (Though they were.)1 Or that CNBC’s version of what issues should be important to American voters was rather bizarrely skewed. (Though it was.)2 It wasn’t even the first question of the debate, where they asked the candidates to tell everyone what their greatest weakness was, then stressed that they were going to hold them to answering the question, and then just sat there watching as each candidate (save Trump) used the question to tell the world how much more awesome than everyone else they were.

No, the worst part was that CNBC had clearly made a decision to go full Candy Crowley, and hold the candidates’ feet to the fire when they answered with false statistics or histories. Which was a noble ambition, and might have led to a truly awesome debate, but for one tiny flaw: The moderators hadn’t taken the time to learn anything about the questions they were asking. When candidates pushed back, the moderators looked lost. When asked, the moderators couldn’t recall where they got their facts. When Becky Quick pushed Trump on a point, and he asked where she was getting her facts, she began shuffling through notes with a confused look on her face, and this exchange actually happened {…}

Vox’s Marcus Brauchli argues that it’s basically American Gladiators, and we’re entitled to it:

The audiences are coming — CNBC and other broadcasters have enjoyed record viewership for the debates — because it’s a red, white, and blue American television mashup of courtroom drama, where tough questions elicit surprise answers; team sport, where even favorite players stumble; and reality TV, where every participant has a unique narrative, moderators stoke controversy, and viewers have a say in who gets voted off the island.

The GOP and Republican Party, however, don’t agree. Which has been responded to as such:

The CNBC debate was a disaster, but fucking suck it up.

— Olivia Nuzzi (@Olivianuzzi) November 2, 2015

Here’s the thing: It’s not really up to the GOP to just “suck it up.” It is not their responsibility to entertain us. They have no democratic obligation to endure whatever silly little games CNBC chooses to go forward with for good ratings and entertaining television. The debates are not a benign service to us, nor a tribute to democracy. They exist for the benefit of the party. If they do not benefit the party, there is nothing wrong with them demanding debates that do benefit the party. I don’t mean “there’s nothing wrong” in the sense that “It’s undemocratic but they’re within their Constitutional Rights”… I mean that they are doing a disservice to nobody because there is no obligation, democratic or otherwise, to even have debates to begin with.

So no, they don’t have to “fucking suck it up.” This is their show.

Now, the GOP could well screw itself over by turning the debates into a prolonged advertisement. That would make it far less interesting to the networks themselves and viewers, and a lot of people would tune it all out. More importantly, it would deprive potential primary voters of a chance to assess how the candidates do with their feet to the fire. I’ve been paying attention to the debates with a particular eye to how well Marco Rubio – a relatively untested figure – handles it. And the debates are helpful for assessing how other candidates, such as Scott Walker and Jeb Bush, might perform in general election debates over which the GOP will have far less leverage (and in that case, rightfully so).

So there is a balance to be struck here. You know who is best qualified to strike that balance? The Republican Party, that’s who. The same applies to the Democratic Party, which in 2007 decided that it would not do Fox debates. The added exposure wasn’t in their interest. That was their call, and they certainly have more stake in making the right one than does any of us.

“Yeah, but the Democrats were right because Fox is hopelessly biased while none of the rest are except for reality’s well-known liberal bias.”

Even if we accept the notion that there is no bias in media towards the left, there is inarguably a bias in favor of an entertaining shitshow, which the GOP primaries might presently lend themselves to but not to which party officials must resign themselves to exacerbating. That requires making demands.

Whether I agree with the complaints and demands is rather beside the point. As it turns out, most of the “demands” are pretty reasonable:

- Opening and closing statements for each candidate that last at least 30 seconds

- Equal time, similarly substantive, and fair questions for each candidate

- No rapid-fire “lightening rounds” (sic) in which all the candidates are limited to a few words in answering questions

- More details further in advance on what the rules, subject, production, and format will be

- Veto power for candidates over graphic and bio information that will be displayed onscreen about them

The only one I consider objectionable is that last one, and even that one is debatable. Any demands greater than that would have required a degree of consensus that would have been hard to achieve among candidates with such contrary interests.

Another thing they’re planning on requiring is that the temperature be 67 degrees. The operating temperature by the third debate shouldn’t even be an issue. Is it outrageous that they demand not to be uncomfortable? Or is it the media’s god-given right to play Egon Spengler from Ghostbusters 2 while ratcheting up the temperature to see how the candidates respond and if they can get Marco Rubio to ask for a disqualifying drink of water.

Everybody comes into debates with different objectives. For the candidates and the parties, it’s about trying to win people over. For the voters, it’s about being informed or at least entertained. For the media, it’s about drawing viewers. Arguably, at least, the parties and candidates do have a democratic obligation to the voters to inform (or maybe entertain) them. But the media? Hurm.

CNBC charged *fifty* times their normal ad rate for the GOP debate, yet the media pretends they are the ones doing the GOP a favor. Come on.

— Josh Jordan (@NumbersMuncher) November 2, 2015

Sure, candidates don't have to let news orgs run debates. And news orgs don't have to give them hundreds of millions of dollars in free TV.

— Nick Confessore (@nickconfessore) November 2, 2015

“Dance for us, clown. Or as journalists we will boycott the presidential primary of one of the two major parties. Because journalism.”

Would you support a request to the prov'l govt to make the last Sat in Oct as Halloween? I am willing to lead this campaign. Thoughts?

— Riley Brockington (@RiverWardRiley) October 31, 2015

First, the province can't legislate when Hallowe'en is. They can proclaim a provincial day of candy-begging. That's about it.

— Jonathan McLeod (@jonathanmcleod) October 31, 2015

They certainly couldn't stop people from asking for candy or giving out candy on Hallowe'en.

— Jonathan McLeod (@jonathanmcleod) October 31, 2015

But the worst thing is taking this communal event, this socially-derived experience, and deciding it's appropriately the government's domain

— Jonathan McLeod (@jonathanmcleod) October 31, 2015

It's not. Not everything we do needs to be micromanaged by a politician or bureaucrat. That *kills* community.

— Jonathan McLeod (@jonathanmcleod) October 31, 2015

We often need help or guidance from govt to facilitate community events, but we need as little as possible.

— Jonathan McLeod (@jonathanmcleod) October 31, 2015

Our lives and communities shouldn't become wards of the state.

— Jonathan McLeod (@jonathanmcleod) October 31, 2015

And of course, such a proposal completely ignores everything behind Hallowe'en. It shoves tradition aside and overly sanitized the community

— Jonathan McLeod (@jonathanmcleod) October 31, 2015

Anyway, when you were a kid, how fun was it to wear your costume to school *on* Hallowe'en? We should take that away?

— Jonathan McLeod (@jonathanmcleod) October 31, 2015

(Yes, they could wear them the day before, but it's not the same thing. There isn't the excitement.)

— Jonathan McLeod (@jonathanmcleod) October 31, 2015

I'll be really disappointed if any of my representatives choose to waste public time on this.

— Jonathan McLeod (@jonathanmcleod) October 31, 2015

(But they are free to spend their personal time on whatever cockamamie scheme they like.)

— Jonathan McLeod (@jonathanmcleod) October 31, 2015

(And yes I know the lines blur, but some time is clearly on-the-job time.)

— Jonathan McLeod (@jonathanmcleod) October 31, 2015

That's my Hallowe'en rant for today.

— Jonathan McLeod (@jonathanmcleod) October 31, 2015

This is the second part of a series on Ryan’s ascent to the Speakership. Part one is here.

There is a natural tendency – especially at Ordinary Times, but elsewhere as well – to characterize the GOP as constantly in search of a hero. Always looking for the next Reagan. Paul Ryan, arguably, was emblematic of this around 2011 and 2012. He became the first congressman to be selected on a presidential ticket in almost thirty years, and the second in well over fifty. A lot of that was his youth, energy, and what was perceived to be his unfailing conservatism. Or something.

Three years later, with Cantor knocked off, Boehner leaving, and McCarthy out, Paul Ryan is once again looked to as the Stalwart of Conservatives. Or, at least, of Republicans. Is this yet another manifestation of the Republicans looking for a hero to save them? Initially, there was some justification for this view. If the idea was that they tap Ryan, Ryan is accepted by the rabble-rousers, and justice is restored to the Kingdom of Elephants. If that was the illusion, it was disabused pretty quickly. And predictably.

It was entirely foreseeable, and I suspect foreseen, that Paul Ryan would be the subject of some immediate pushback. That the guy who was considered Mr Conservative three years ago would suddenly become Not Conservative Enough. Because of course he is. Because of course they would. They could theoretically have declared victory. “See? For all that you fellow Republicans hate us, we replaced a less conservative option with a more conservative one. This is why we fight!” But to have embraced victory would be to embrace responsibility. It would embrace being accountable to those who have no sense of what tangible victory would look like and to people whose only sense of victory is another notch in their belt.

So, it is of no surprise whatsoever that many of the same elements that lambasted Boehner immediately started in on Ryan. It is no surprise that Ryan would become the next pachyderm metamorphosed into a rhinoceros. Many of them have lost sight of who they are fighting, or what they are fighting for. The fighting has become a thing unto itself. The belt-notches have become not a means to an end, but an end unto themselves. They fashion themselves warriors, but have become nothing more than reavers for fun and profit. They imagine themselves heroes, but are more reminiscent of Charlie Sheen shouting “Winning!” and “Tiger blood!” (more…)

This is, obviously, more of an OT piece. But here it is for your reading enjoyment. Part one of two.

When Atlas says “This is not what I signed up for.”

If all goes according to plan, tomorrow Paul Ryan will be elected Speaker of the House. He didn’t especially want the job. He was nowhere in the general historical order of succession towards the speakership. But these are special times. How did we get here?

I’m not going to get into the Tea Party and PPACA and all that, because everybody knows – or think they know – the important aspects of it. Rather, the often overlooked event was the budget battle of 2011. With the threat of a shutdown and the debt ceiling, Speaker Boehner and President Obama worked out a compromise that included some immediate budget cuts and the promise of more down the line (with the threat of a sequester). Historically, compromises like this are celebrated and grumbled at by both sides and life goes on. This time, however, things went off-script. Almost immediately, Republicans were declaring resolute victory. Outsized expectations that Obama would go down in 2012 were born. But then people started looking more closely and the cuts that Boehner had extracted at the front-end were largely illusory. Then it was the Democrats who were declaring victory and Republicans who were scrambling.

There were three lasting political effects from the budget of 2011. The first – as described in Double Down – is that President Obama was extremely ticked off that what was meant to be a good-natured compromise was (initially) portrayed as such a Republican victory that embarrassed him, and he made the determination that would not happen again. The second is that Boehner lost the trust of the already ornery Tea Party and hyperconservatives in his party. The third is that it planted the seed for the Sequester.

In 2012, true to his word, President Obama did not compromise (much) in the budget process. This led to Boehner folding in order to avert crisis. That lead to more raucous cheering among Democrats. This victory was followed up on January 1st by the delaying of the Sequester, which again peeved conservatives, the Tea Party, and pretty much everyone important to Boehner’s Speakership. Shortly after newly elected congress convened in 2013, the Sequester went into effect, giving at least the illusion of a major Tea Party victory amidst a sea of losses – most specifically the presidential race, as well as senate races, both of which were laid at the door of The Dreaded Establishment. Message: Tea Party winners, Boehner loser. (more…)

Back home, there was a little town that had a little stretch of the Interstate that would go out during rush hour and ticket cars for driving underneath the minimum speed limit. the tickets were junk because the law also has a “reasonable and prudent” standard, but a lot of people would pay the fine just to avoid having to show up in court. It stopped at some point, though I am not sure by what mechanism it was stopped.

And with that, where better to find cars to ticket for inspection violations than a repair shop:

Bruce Redwine had seen enough. After years of watching a Fairfax County parking enforcement officer slap tickets on his customers’ cars for expired tags or inspection stickers, usually as the cars were awaiting state inspection or repair at his Chantilly shop, he snatched the latest ticket out of Officer Jacquelyn D. Hogue’s hand and added some profane commentary on top. {…}

They don’t understand why Fairfax police have zealously sought to enforce laws on expired tags or inspections, mainly on drivers who are making the effort to get their cars into compliance, while on private property. Hogue’s appearance in the industrial park often set off a scramble to hide customers’ cars inside the shops, the shop owners said.

“They’re harassing the small businesses trying to make it in this tough economy,” said Ray Barrera of A&H Equipment Repair. He estimated that his customers’ vehicles had been hit with $60,000 worth of fines and fees over the past six years.

Fairfax police said they are only on the property because of a letter issued by Mariah’s property management firm in 2009, specifically granting police permission to enforce county traffic, parking and towing ordinances.

Revenue-hungry Fairfax County is thinking about expanding the use of volunteers to write parking tickets after a five-year decline in the number of citations issued and amount of revenue collected.

The Board of Supervisors’ auditor of the board made the recommendation in a draft report that found citations had declined about 16 percent over a five-year period. Revenue fell about 5 percent despite a boost in the amount of parking fines and expanding the number of parking ordinances, the audit says.

To beef up collections, county auditors recommended that Fairfax follow other jurisdictions that have created special units of volunteers to enforce parking violations. Supervisor John W. Foust (D-Dranesville), who heads the audit committee, said he would forward the recommendations to the full board.

The worst thing of this sort to happen to me involved the former complex I lived in with my ex-roommate Karl. On New Years Day, Karl woke up to find his car missing. It seemed unlikely that someone would steal his decent but nothing-special car. He wondered if there had been some mistake, so he called the tow company on the sign in the lot and sure enough, they’d towed it. As it happened, his registration had expired with December. He asked if they were just going from car-to-car looking for expired tags. While that seemed aggravating, the truth was infuriating. No, they said, the apartment managers keep a running list and as a part of their towing contract turn over a list at the beginning of every month. As best as we could determine, the apartment complex got money from the towing company, which got money from the county.

When confronted, the apartment complex was entirely unapologetic. They basically said, “Well, you should have renewed your tags on time, shouldn’t you?”

The same is technically true of those who go to Redwin’s shop after Inspection has required. They could avoid all of this by crossing their T’s and dotting their I’s and taking care of everything on time.

The question is, though, what is the goal supposed to be here? The goal is to get people to pay for their registration and/or have their cars inspected as required by law. There are multiple ways to go about this, and consequences do have to include ticketing, fining, and at some point towing.

What the three stories have in common is belying the more powerful motivation of people trying to extract as much money as possible from people to feed the system. Whatever, system, really: Private apartment complex, private towing company, county coffers, state coffers, and individual agents whose job it is to meet their quotas management mandated goals. Which leads to some perverse incentives.

There is really no excuse to target people trying to correct their inspection situation because they are an easy target. To the extent that widespread delinquency is a problem, it makes sense to add on a general fine for late registration or inspection. I’m honestly really surprised when a state doesn’t. Back home, there is no special charge for delinquency, but whenever you do register while delinquent you are registering retroactively to prevent you from benefiting from your own lapse. Here, they don’t even do that, which is in my view excessively generous.

I don’t know what’s the case in Fairfax County and/or Virginia, and I’m honestly not sure it matters because it wouldn’t surprise me even a little bit if they got more money for delinquency and then more-more money for tickets. Fairfax County – in addition to not being a very right-wing place – has gotten a windfall from escalating property values and property taxes, but here they are. More generally, there just doesn’t seem to be much relationship between anti-tax sentiment and creative revenue-generation. I would prefer services be paid for mostly out of taxes and fair fines, of course. In part because the fines are most specifically what pays the salary of those who think its a good and fair idea to go to inspection stations to ticket people.

This post is not about the virtues or detriments of of gun control specifically. It is more about the philosophy behind the positions. If you want to argue about gun control policy specifically, I recommend doing so in the preceding thread linked below.

Last week, in my vent about the gun control debate, Murali asked the very sensible question… what’s so wrong with gun control:

Unless you are an anarchist, you think the state is justified. Moreover, one of the basic functions that you think the state can legitimately perform is internal security. Clearly there are some ways in which the state may infringe your property (or more properly your holdings) or else the state could not even tax you to fund a police force. Clearly too, there are some measures which the state may not take (e.g. the patriot act) to ensure security. {…}

Weapons are not morally innnocent property, but belong to a type which is intended to inflict violence, something that is prima-facie illegitimate.

A weapon is a tool that is intended to inflict violence or the threat thereof. Even in defensive uses of a weapon, the weapon has defensive use only because it can threaten the aggressor with violence.

The precise justification for the existence of a state (i.e. an entity which maintains a monopoly on the legitimate use of force) is that the complete liberty to use force as and when you see fit would be horrible if everyone had it. The basic fact is that it is very nearly always an improvement of the state of affairs when this liberty is curtailed to some significant extent. Just thinking how far away we are from a Hobbesian state of nature in terms of our liberty to inflict violence on one another as and when we see fit and correspondingly how much better off we are as a result underwrites the justification for the state. That is to say, to say that the state in general (or in most cases) is justified just is to say that the delegitimisation of most private violence is justified.

My response was that I am not in favor of gun ownership as a universal right, but rather that it’s context-independent. I might well support rigorous gun control in Singapore while opposing it in the United States. There are a number of reasons for that, involving history, geography, and culture. Which Murali describes as a “pragmatic matter.”

That’s partially, but not entirely correct. I almost said as much in the thread, but Gabriel touched on it himself:

For me, I’d say it’s almost completely pragmatic. But sometimes some measures are so impracticable that to pursue them would be almost a wrong in itself. Not that there isn’t potentially a lot that can be done, like registration or coding bullets with identifying information, and perhaps requiring owners to carry liability insurance.

I also believe in something like a natural right to self-defense, which implies in my opinion the right to legal access to some of the means of self-defense. Those means don’t have to be firearms, but in a heavily armed society, I’m willing to concede that such access is part of the right.

When it comes to hunters, I don’t have a problem with them. I don’t particularly want to get in the weeds over whether they have a “right” to their firearms (leaving aside the question of the 2d amendment) or whether it’s merely sound policy to let responsible people hunt.

The middle paragraph is important. In a context where you could actually keep guns out entirely or almost entirely, and where guns are not embedded deeply into the culture, it seems highly desirable to keep them out of the hands of the people. However, once they are widely available, it’s not just impractical to try to put that cat back in the bag, it does border on the immoral. That is partly because, as Gabriel says, a general right to self-defense. But it’s also because of how troublesome it is to make harsh laws against what is culturally commonplace. Which brings me to Christopher Carr’s post Over There about Saudi Arabia’s caning an elderly man and whether or not we can call that barbaric. To which Maribou responded:

My problem with these kinds of comparisons is that “our” society is very difficult to view objectively, and so trying to compare it with another one is a tricky business.

Is it really so much better to lock people up in prison for years or decades for smoking pot?

It’s not like long prison sentences don’t carry the same kind of risks to life and limb that caning does.

(I think it’s abhorrent, what is going to happen to that man, and what happens to women in Saudi all the time. I just think our equally abhorrent things get a cultural pass, so there’s not much point in trying to valorize our own culture based on its ideals rather than its practices.)

And Dragonfrog added:

I came here to make that point.

I have seen nothing to dissuade me from holding that drug prohibition has to be considered as a whole – whether the prohibited substance is ethanol, caffeine, THC, morphine, cocaine, LSD, etc., it is either barbaric, or it isn’t. There don’t exist two categories of drugs, one of which one can non-barbarically prohibit and the other of which one cannot.

Given the above, the only question that might produce a contrast between Saudi Arabia and the US or Canada is whether caning is more or less barbaric than imprisonment or asset forfeiture.

First, I would say that “barbaric” is an awfully heavy word. And with that, even if our own failings in this regard do not approach Saudi Arabia’s, they’re close enough that it’s hard to see how the line between here and there being the line between “civilized” and “barbaric” is anything but a self-interested rationalization. If they are barbaric, then so are we. And if we are not, if we can (even while disagreeing with our own policies) see nuance, Saudis should be afforded the same generosity of nuance.

At the same time, if Dragonfrog is arguing that prohibition is an all-or-nothing deal, that we cannot view differently a society throws people in prison for dealing in lactose milk due to some religious observance and one that throws people in prison for dealing in cocaine… I can’t really agree with that. They may both be barbaric or neither be barbaric, but they’re in different points along the spectrum.

While I do not presently favor blanket decriminalization, I don’t defend the War on Drugs, or the hard hard we use in its enforcement. taking a soft hand, of course, may result in more people doing more drugs. At the very least, a War on Drugs that is never fought definitionally cannot be won. That means, among other things, accepting that people are going to die doing (many) drugs. They’re going to ruin their lives. Of course, the War on Drugs hasn’t stopped any of that. But what if it could? Or rather, what if it could make it exceedingly rare? Would you support it then? A lot of libertarians wouldn’t. I might.

The War on Drugs ruins lives. It rips children away from their parents. It sends otherwise relatively law-abiding individuals to prison. Fathers, sons, mothers, daughters. It can wreck the lives of people who would otherwise never harm anyone. To be willing to do that, you must have a degree of confidence in your success. To do otherwise isn’t just a misallocation of resources or unwise policy. It crosses the line from being merely misguided to being actively harmful dependent entirely on the context.

And that’s where I’m coming from when I talk about taking a different view on guns depending on the context. In that sense, it really is a matter of pragmatism. However, it doesn’t really stop there.

A light-handed approach would be largely ineffectual. A heavy-handed one would be actively harmful. Like the War on Drugs, it would be unsuccessful in the United States. Geography, history, and culture. And we would be left with the choice of throwing fathers, mothers, and sons into prison. Of taking children out of their homes and putting them into a foster care system that is more dangerous than a home with a gun in it. Throw in prosecutorial discretion, and you likely have selective enforcement and racist enforcement. You likely have escalating sentences to keep induce more and more compliance. Pursuit of the goal of getting rid of most guns in this country would likely require burning the village to save it. And then, not actually saving it. That may not be the goal, but I do see it as the result.

Nobody envisioned flashbombing cribs when it was decided that drugs should be illegal. We got there through an increasing desire to win The War and, perhaps most importantly, an increasing indifference to offenders. The amount of animosity towards gun owners is already immense. Gun owners injuring themselves is joke fodder or and just last week a writer at Salon said injuring them should be public policy. And in a way, it’s rational. If these people are responsible for the deaths of countless others, why should they be treated as people and not like any other criminal? Why should they be immune from jail? And on and on.

But that’s what something being illegal means. You can have intermediate steps. You can have jail as the last resort. But the more stubborn the populace, and the more justified they see themselves as being, the more people you’re going to have to take stronger measures against. That’s the question that you have to ask yourself. You have to break eggs to make an omelet. But understand the eggs, and understand the omelet. Breaking eggs to know end isn’t just impractical.

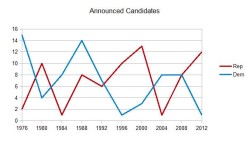

Dr Phi wants to know why the GOP so frequently seems to have more candidates than the Democrats:

But since 1992, it seems like the Democrat field has never been as crowded. Of the three elections since then in which the Democrats haven’t run an incumbent, the number of candidates with non-trivial delegate counts or vote totals have been:

2000: 2 (Gore, Bradley)

2004: 4 (Kerry, Edwards, Dean, and Clark (barely))

2008: 2 (Obama and Hillary)

The Republicans, in contrast, run more candidates:

1996: 5 (Dole, Buchanan, Forbes, Alexander, and Keyes

2000: 3 (Bush McCain, Keyes))

2008: 4 (McCain, Romney, Huckabee, and Paul)

2012: 4 (Romney, Santorum, Gingrich, Paul)

Which brings us to 2016. The Democrats have two declared candidates (Clinton and Sanders), one undeclared candidate (O’Malley), and one rumored to be testing the waters (Biden). Meanwhile, the Republicans have some 15 candidates serious enough to participate in one of the Fox debates.

Methodology is a bit of a question here. He uses the number of candidates with non-trivial delegate counts. That’s one way of going about it, but it’s a relatively rough measurement for how many candidates each party has. It may well be true that the Democrats weed candidates out more quickly than the GOP – or maybe not – but delegate rules differ between the parties and it excludes entirely candidates that at least in some point in the process had credibility (think Edwards in ’08) and included some with little (Alan Keyes). I also wanted to go back further than 1996.

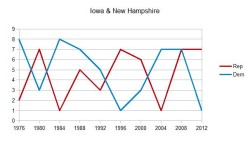

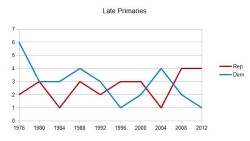

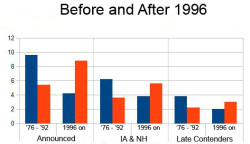

So I looked at three different metrics: How many candidates actually announced (the GOP will have 17 by this metric)? How many were still there in Iowa and New Hampshire (so Perry and Walker would be excluded from this count)? And how many were around for the long haul? The last one was most difficult, but I defined it as getting more than 10% of the vote in any state (excluding their home state) in one of the last 25 primaries. I went all the way back to 1976, which was the second election in the primary era and the first that included competitive races for both parties.

The end result is… well, there’s just not that much difference in the parties in the longer run. Since 1996, there is, but that’s because it excludes the two elections where the Democrats smelled blood and had huge fields and no obvious candidate (1976 and 1988). Since then the GOP had large fields (ten or more announced candidates) three times (2016 is the fourth) while the Democrats haven’t. However, in terms of announced candidates the Democrats actually had eight in ’04 and ’08. But the end result going back to 1976 is that the GOP had an average of 7.1 candidates compared to 6.9 for the Democrats. The numbers don’t actually change all that much if you look at Iowa and New Hampshire or candidates in the race for the long haul. The Democrats have 5 and 2.9 respectively, compared to 4.6 and 2.6 for the GOP.

–

–

–

–

If you look at announced candidates since 1996, you do get the biggest difference of 8.8 Republicans to 4.2 Democrats. By the time we get to Iowa and New Hampshire, there’s still a difference but less of one as there are 3.8 Democrats to 5.6 Republicans. By the end of the primaries, it’s 3 to 2.

So that’s… not insignificant. To the point that it complicates the original “the parties are the same” thesis. The question is, how significant is it? Why has the tide turned? Before this year, the two largest fields were Democratic ones before ’96, but since then the Democrats haven’t hit ten once while the GOP has three times?

So that’s… not insignificant. To the point that it complicates the original “the parties are the same” thesis. The question is, how significant is it? Why has the tide turned? Before this year, the two largest fields were Democratic ones before ’96, but since then the Democrats haven’t hit ten once while the GOP has three times?

The most obvious question is whether this is merely a product of incumbency, but if that’s a factor it’s not an especially large one. Especially over the whole data set, where the GOP had two uncontested primaries (1984 and 2004) as did the Democrats (1996 and 2012). Republicans had contested incumbents in 1976 and 1992, but so did the Democrats in 1980. Broken down to before 1996 and after that does skew things a little bit, but the overall trends hold even if you entirely exclude incumbent party primaries.

One possibility is that there are just random trends and it will go back and forth. Or maybe it’s not random. A theory I can imagine gaining traction is that it coincides with the crazification of the GOP and it’s a symptom of that. If so, though, how crazy were the Democrats during the 70’s and 80’s? Maybe very crazy, if Jane’s Law (“The devotees of the party in power are smug and arrogant. The devotees of the party out of power are insane.”) has any traction. Or if we wish we can come up with a benign reason for one and a less-than-benign reason for the other.

Notably, though, most of the largest fields have come in circumstances like 2016, where one of the parties has been in office for eight years. That ties into my (very tentative theory), which is that large fields come when parties are trying to find themselves and dealing with internal conflict. In 2008 and especially 2000, despite in each case the party being out of power for eight years, there had been a consensus on which direction the party should go. The Democrats had eight candidates in 2008, but they did not represent terribly different visions of what the Democratic Party should be and was mostly a matter of who should advance that vision. In 1976, candidates ranged from George Wallace to Scoop Jackson to Jimmy Carter. It’s more complicated in 1988, but you can still see it. And in 2016, it’s very much there.

That’s just a theory, and not a hill that I am going to die on defending. And it relies on a degree of chance. The problem with the political science of presidential elections is that the sample set is always small. Sure, we are nearing sixty elections, but the facts on the ground change regularly. The parties and issues and coalitions change. With primaries in particular, there have only been eleven elections that they’ve picked the nominee, and those eleven elections have taken us all the way from Vietnam to here.

Perhaps the biggest mystery to me, to be perfectly honest, is why – with all of the senators and governors and celebrities looking for their chance to shine – we don’t have a dozen or more candidates every election.

Libertarianism doesn’t have a lot to say about the good life. It doesn’t tell me whether I should give to charity, whether I should save a drowning child, whether I should be a loving husband, or whether I should devote myself to uplifting intellectual pursuits instead of squandering my life watching TV and eating bonbons. Is an unexamined life still worth living? Libertarianism doesn’t say.

At least not much. I’m referring to libertarianism as one thing, but there are a lot of libertarianisms. I’ve never read Ayn Rand but those who claim to, and are critical of her, say that she advocates a life of selfishness or self-centeredness. Maybe that means, for her, the good life is looking our for number one? (Maybe this more charitable and better-informed account serves her better. I don’t know, but I trust its author.)

Rand’s not the only libertarian. As with Rand, I’ve never read Rawls, either. But my understanding is that his libertarianism rests on a notion of fairness: what would we have the world look like if we didn’t know beforehand what privileges we’d be born into? Others (Murali, if you’re reading, I’m thinking of you) can clarify how I misunderstand Rawls, but it seems to me he advocates something like a golden rule. In that sense, the good life is doing–or advocating for, or building society along the lines of–how you would be done by.

A better example, because I’ve actually read some of his stuff, is Jason Kuznicki. He has urged us, for instance, “to refuse to be ruled–and refuse to rule.” By that standard, maybe the good life is a studied and reflective humility. Even if I’m misrepresenting him, I think it’s a good lesson at any rate. A thousand flowers can bloom, as the cliché says. Or to paraphrase James Hanley (I forget the cite), a strongly libertarians society has more room for traditionalist Hutterites than a strongly Hutterite society would have for just about anyone else.

Still, libertarianism does its best work as a naysayer. It has a lot to say against the excessive uses of state power and about the costs of even the best intended programs. Liberals and conservatives and anyone else who wishes to use the state for any purpose had better heed libertarians’ critique against coercion and for expanding choices. Some fringe elements notwithstanding, most members of team liberal or team conservative value individual autonomy.

Even as a naysayer, libertarianism offers a clue to the good life. Its advocates seem to have a faith in human resilience if only the fetters of coercion be removed. Along the lines of what James Willard Hurst argued 50 years ago in a different context, many people await the “release of energy” that can move them to ever expanding choices, opportunities, and prosperity. There’s a good here, and the good is in removing impediments to finding the good.

But nagging questions remain. Prosperity and abundance count for a lot, but can there be too much? We’ll all die eventually anyway. The fear of death disturbs me even now.

And while still alive, how to deal with all the complexity life offers? Local communities and autonomous agents have a way of forming their own complex and sometimes restricting rules and obligations. While these can be chalked to the outcomes of market exchanges or daily micro-compromises and while a strongly libertarian society widens the opportunities for exit, they still impose ought’s and should’s on those who don’t choose exit or for whom exit is still too costly or who choose exit and find only other obligations or (maybe worse) themselves.

Liberty, by itself and however you define it, doesn’t have the answer.

Over There a while back, Jon Rowe posted about his experience selling his car to a tow driver {followup} {followup} {followup}. The basic order of events was:

- In Pennsylvania, Rowe’s car broke down and he sold it to the towing company for a nominal sum.

- The towing company did not properly transfer ownership of the car to them. They instead put some New Jersey plates on it and left it for sale on the side of a road in the Garden State.

- New Jersey authorities considered the car abandoned. They tracked down the title to Rowe through Pennsylvania. They contacted Rowe about paying a fine.

- Rowe talked to the authorities in New Jersey, explained the situation, offered the bill of sale, and was told that was the end of it.

- Months later, is contacted by the New Jersey courts with a summons to appear and the threat of arrest for a failure to do so.

Through this, Rowe railed against the immutable bureaucracy. While he was able to navigate the system, this is exactly the sort of penny-ante thing that snowballs and lands people who aren’t lawyers in jail.

The response was, overwhelmingly, “Screw you, Jon.” Well, that’s not quite right. The criticisms fell into three categories:

- Rowe is the villain here who got what he deserved. Rowe sold his car to someone he shouldn’t have and any and all negative consequences of doing so belong to him because he didn’t do due diligence.

- Rowe is the villain here who got what he deserved. There were rules and he didn’t follow them. At first it was the assumption that Rowe himself was supposed to transfer the title and didn’t. That turned out not to be quite true, so then it was a fixation on the license plate. Rowe was supposed to turn it in and didn’t. There is reason to believe that the course of events would not have changed even if he had turned in license plate – because he would have been turning it in to the same people who failed to transfer the title – but that didn’t matter because Rowe had Failed The Bureaucracy and because he sold to the wrong person.

- There is literally no way that this could have turned out differently than it did, given the previous two items. No way at all. There were repeated demands that Rowe outline precisely how it could have gone differently and saying that he couldn’t because this is how it had to happen. Even the part where New Jersey had told him not to worry about it, Rowe was talking to the wrong person and therefore was to blame and the bureaucracy cannot be expected to deal with that. You cannot possibly expect the bureaucracy to be able to accommodate user error.

All of which actually made Rowe’s points, and other points, more forcefully than Rowe did. Truth be told, I thought that some of Rowe’s criticisms of the bureaucracy were off-base. he criticized Pennsylvania for not cancelling the title of his car, but in all honesty I think that such cavalier canceling of title would do more harm than good. I think the system did work, as well as can be expected, right up until he was told by New Jersey officials that it had been taken care of and it had not been taken care of. I can even give them a pass for the whole “Respond or go to jail” thing because I do think that particular stick is probably necessary.

However, because that’s the stick, I do believe that it is incumbent on the system to make avoiding that as easy as possible. While various critics of Rowe did agree that the system could be streamlined and made easier, but treated doing so as an act of benevolence on the part of the state rather than an imperative to keep people from needlessly going to jail. And the assumption that because it is that way that it has to be, which simply isn’t the case. Several people reported having been in a similar circumstances but with bureaucracies that handled the situation differently. My father had a title-non-transfer issue and it was taken care of easily and without fuss. It’s not some tangential that such alternatives are possible, or something that the state might want to do because wouldn’t it be nice, but rather it’s something extremely important.

But at the end of the day, Do Not Fail The Bureaucracy was the order of the day. And though Jaybird was criticized for making the comparison, it really did seem to me to be the equivalent of “Don’t talk back to the officer or you own the consequences.”

Leaving aside the fact that the same consequences would have occurred whether he had turned in the license plate or not, that’s a somewhat disturbing attitude. As was the pouring over the record finding a way to make sure that it was Rowe’s fault. And especially the bit about Rowe demonstrating classism by believing he’s too good for a Trenton jail.

And so Rowe’s point was made, emphatically, by his critics. So, too, was a stronger and more important point that Rowe wasn’t especially trying to make: People lose their minds when it comes to anything political.

The truth is that I probably could have posted complaints about the DMV Over There instead of over here and even though certain aspects of my recent difficulties were my fault, a good chunk of the response would have been sympathy for the inconvenience instead of blame for Failing The Bureaucracy. However, since Rowe approached it as a political matter, it was responded to as a political matter. And advocates took on the role of prosecutor. No holds barred. Though it’s less true than it used to be, you can still complain about the DMV, or Comcast, without people assuming that you’re being political and not responding politically. For now, anyway.

But once it does, everything does change. Perhaps the most recent example of that is Ahmed the Clock King. There are multiple angles from which to view the story

- The Ahmed story is indicative of anti-Muslim prejudice.

- The Ahmed story is indicative of how out of control zero tolerance policies and excessively anxious administrators have become.

- While it turned out to be unnecessary, the actions of officials were completely justified behind the veil of what was unknown.

- Ahmed is a bad kid who wanted to freak everyone out and therefore the response was entirely justified even knowing what we know now

At the outset large segment of the left (and not just the left) went straight to #1, and a smaller segment on the right went to #4. A lot of people initially landed on #2… only to graduate to #3 and #4. It was interesting to watch, and very much reminded me of the Rowe row, because it seemed to be an immediate response to the political implications of the whole thing. It’s hard to separate #2 from #1, and if #1 scores points for the left, then those talking from #3 and #4 are suddenly making more attractive arguments.

The end result of which is that a lot of people start latching on to some pretty flimsy arguments. As if it matters that Ahmed was using a very liberal definition of “made” when he said he made the clock. As if it matters that his family has a bit of an activist streak. It seems to me that even if it was a deliberate prank, it was kind of a lame prank and that the school and police were not only successfully baited but responded the way that they did remains the focal point of the story.

Unless you’re committed to ceding no political ground whatsoever unless you absolutely have to. In which case, all of that becomes important – like Rowe’s failure to turn in the license plate in a manner that almost certainly didn’t matter – because it’s all you have. Ahmed is the villain here. He has to be. He has to be.

Photo by DonkeyHotey

Labour didn’t have a “primary” per se, but it had the closest thing to which the UK has ever seen. Instead of leadership being determined by active party members, it was determined by more or less anyone who wanted to participate. Or at least anyone willing to drop a modicum of coin to do so.

Combine this with Trumpmania, and it starts to fill in a pretty strong case against primaries. Now, my criticism of Trumpmania is not based (solely) on my disagreements with him and the direction he would take the party… but because he is a tourist. He has little invested in the party. There don’t seem to be very many issues that he has particularly thought about or cares about. He’s found The Issue, and most of the rest is just attitude. If it were Jeff Sessions or Tom Tancredo running on the immigration issue and/or economic populism, I’d be worried about now. I’d be worried that “Wow, this is what the other party is going to be.”

But Trump is Trump, and I still can’t think of him as a potential president. What mostly concerns me about him is the extent to which he has taken an already flawed process and runs a non-negligible risk or distorting the entire thing. He could hand it to Jeb Bush, or hand it to Ted Cruz, depending on how the chips fall. The result is entirely the point. The sticking point is what primaries are supposed to be doing, and what they are doing.

We seem to have fallen into this notion that primaries are supposed to be expressions of democracy at work. Except they’re not, really. The parties aren’t governments that owe particular rights to its people. Parties are organizations with a more sectarian purpose. It is just as legitimate for a political party to choose its nominees by lottery, or people smoking cigars in the back room, than it is with an open vote. People can like, or dislike, the result of these selections (or the process), but that’s not some grand Civil Rights Violation, as it would be if people were being prevented from voting at all, but rather an objection that should be registered by voting for the party with the candidate you prefer. Theoretically, that alone prevents parties from nominating too stupidly.

Of course, the parties (or at least one of them) is pretty stupid when it comes to selection process. Jeb Bush is a terrible candidate. But even before he was a terrible candidate, he was still a terrible candidate. He was practically inviting a revolt by the rank and file. He was inviting 2016 to be the first election in at least 35 years (more accurately 50) where the challengers actually won. I had the outline of a post about what was shaping up to maybe be a huge Bush/Walker battle, but it could have been any number of people (a field that widened as Jeb demonstrated himself a worse and worse candidate). But the challengers went with Trump. Because of course they did because they haven’t a tactical bone in their body, Trump is what happens when you decide to vote with your viscerals, and because primaries are terrible and stupid.

Except… here’s the thing.

Photo by DonkeyHotey

We don’t have a parliamentary system here. We don’t have a multi-party system with mixed-member districts, but we don’t even have a parliamentary system without that, like Canada does. We have a more complex system with the two parties virtually hard-coded in there. The barriers to entry are exceedingly high. A new party outside the duopoly would not just need to get more votes than the other two parties to win the presidency, but would need a majority of electoral votes or (likely) need to have a majority of the congressional delegations in a lot of states. That’s why we haven’t seen a durable new party in over 100 years and it’s entirely possible that we won’t again for another 100.

We have a two party system and while there is no telling what the parties will stand for in 100 years, there is little doubt that they will either be called the Republican and Democratic Parties or will be a direct rebranding of one or the other. And if there is a revolution within the party, it’s as likely as not to occur through the primaries. While the populist impulse of primaries can lead parties towards more populist candidates, the lack of any primary system can lead to an unaccountable stagnation and if the parties are immutable that’s a real problem.

So I am not yet at the point where I am ready to completely disregard primaries. I would gladly take it as part of a suite of other reforms (getting rid of the electoral college, IRV, fusion tickets, etc), but I’m not there yet on its own. Labour has time to self-correct, Trump is stagnating, and maybe all is a bit closer to being right with the world.