Category Archives: Statehouse

Charles Lane argues that we should have fewer elections, for Democracy’s sake:

One of political science’s better-established findings is that “the frequency of elections has a strongly negative influence on turnout,” as Arend Lijphart of the University of California at San Diego put it in a 1997 article.

Yet in the United States, we constantly hold elections: Every two years, we elect a new Congress and, in many states, a new legislature. Every four years, that’s combined with a presidential election. Some jurisdictions squeeze local balloting — for sheriff, school board, judge, coroner, you name it — into the years between midterm congressional and presidential elections. Of course, these are often twice-a-year exercises, since a primary precedes the general election. Sometimes primaries have runoffs!

The United States and Switzerland don’t have much in common, but they both have (a) frequent elections, with Switzerland holding at least three or four national votes per year, in addition to cantonal elections, and (b) relatively low voter turnout. A mere 49.1 percent of registered Swiss voters cast ballots in the 2011 national parliamentary elections.

First, I believe there is some truth to this. For instance, we have far too many elected officials. First off, we elect judges when we really shouldn’t. But whether we think judges should be elected or not, for a lot of urban voters it overstuffs the ballots considerably. When I lived in Colosse, there were over 300 judgeships, and while their elections were staggered over time, there were still scores of them every single election. When I first voted at 18, I read up on every single race. But political nerd that I am, that didn’t hold up after the first few elections. I would vote straight-ticket Democrat on the basis that Colosse County was Republican and any Republican judge close enough for my vote to matter was probably a lousy judge. (Colosse County is now not so red, so I don’t know what I would do.) There are also multiple executive positions at every level of government, many of which probably don’t need to be independently elected. I also question the city/county distinction and believe that as often as not we should merge those governments.

It’s also true that we have too many election days. This includes bond elections, periodic recalls, and special elections to fill vacancies. It seems reasonable to me that we should be able to reduce elections to an annual affair without too much of a problem. There may be some emergency bond election that may not be able to wait until November, and I think provisions can be made for those such as requiring turnout thresholds. If you can’t get more than 30% of voters to show up to vote for it, it can’t be all-important. I am not a fan of recall elections generally, but absent something impeachment-worthy (where impreachment is a possibility) the solution is to work it so they’re up for election the next November along with whatever other elections are being held. And I believe we can – and should – restructure how we handle succession in case of a death or retirement. I also support IRV to avoid runoffs (and hell, maybe do away with primaries).

Beyond that, though, I believe that holding national elections every four years – and only every four years – is a terrible idea. I don’t believe that it’s too much to ask voters to come out once a year. I’m open to “voting week” instead of “voting day” if that’s the hangup, despite my general skepticism of excessive early voting opportunities. And voters who can’t be bothered to vote once every two years don’t especially deserve to have their voices heard. This may create some discomfort at the national level with the “two electorate problems” but canceling elections is a permanent solution to a temporary problem. Realignment is constantly shifting, and the situation will resolve itself at some point. I prefer both the voter feedback that midterms can provide, as well as having different elections devoted primarily to different levels of governments. While the US may be a bit of an outlier when it comes to the sheer number of elections we have, in parliamentary federal republics provincial elections often do not align with national elections (and shouldn’t).

If I were in charge, we’d have election week every November basically going presidential-local-gubernatorial-local. It wouldn’t be strictly federal-local-state-local since legislator elections at the state and federal level should still be staggered, but that does have the advantage of boosting turnout somewhat while also allowing the focus on elections to be more federal some years and state the others. I’m not reflexively against having state elections on odd years and avoiding that, though presidential-gubernatorial-local/congressional-local/gubernatorial lacks elegance and I’d need to look up how it affects turnout in odd-year states (Louisiana/Jersey/Virginia).The current system is messy, and apart from certain electoral advantages I can understand the impulse behind deciding that policy should be decided (perhaps even at all levels) on very periodic elections but where most people show up, but I would prefer that be balanced with tighter feedback and a bit of separation between state election years and federal ones where the issues are often different. By all means, we should look at reducing the number of elections we have, but within limits.

Warning: In this post, I’m going to use something that somebody said in order to make a point that I would have tried to make even if I couldn’t find anybody who said it.

Four years ago, at around the time that Scott Walker was doing what he did to public employee unions that made himself famous, Doug Mataconis wrote a critique of public employee unions to which I’m largely sympathetic. But Mataconis ends with this almost throwaway sentence:

The party is over guys, and your days of feeding off the government trough are coming to an end.

My problem with that statement is that it’s unnecessarily confrontational and a goad to anyone who sees the issue differently to knock the chip off his shoulder. As a public employee who for a long time thought he was in a public employee union* and who works with other public employees, most of whom are in said union, I’ve heard enough complaints about how those who oppose public employee unions don’t care about the workers and are trying just to demonize the mostly minority employees who make up the bulk of public employees.

I’m not well-versed in the rhetoric of those who oppose public employee unions. But it seems hard to find one, especially if he or she holds elective office, who doesn’t choose to demonize public employees in some way while opposing such unions. Too few people maintain that it’s possible such unions represent mostly hardworking, well-intentioned people, and yet those unions just don’t function well for the state, for taxpayers, or for people who rely on the services provided by those employees. (Yes, I know some public employees who seem to just phone it in, and that’s a pretty big problem. But it’s not the sum total of the problem.)

Again, I’m tone trolling Mataconis’s piece. The rest of his article makes mostly an argument about why such unions can present a problem, and that argument and similar arguments need to be part of the discussion. But if those who oppose public unions wish to garner more widespread support and not appear to be merely partisan hacks, they should make the case on the merits and shy away from the “government trough” language.

*I got very mixed messages as to whether I was in the union. When I finally got up the courage to formally rescind my union authorization card (Sangamon is a card check state for public employees), I was informed that I wasn’t in the bargaining unit anyway, even though the union let me vote on the contract back when it was up for consideration. Fortunately, the union had never deducted dues, but I had walked out with it when it did a short strike, and in retrospect, doing so without being in the bargaining unit put me in danger of being fired. I shouldn’t have walked out anyway since I didn’t agree with the union, but I didn’t want to be “that guy” who scabbed.

I used to think being gay was wrong. I supposed that if you asked me, I would have said “being gay” wasn’t wrong, but “choosing to live as a gay person” was. I’m not sure I made that distinction at the time. I also thought it was appropriate for the state to encode its objection against homosexuality in its laws. While I probably would not have supported outlawing gay sex or instituting/continuing a formal program against gays, I believed the state shouldn’t offer any protections to gay people as gay people.

For example: In 1992 (I was 18 then), Cibolia had an amendment up for consideration by voters that would have invalidated then existing civil rights protections for gay people. These were laws that Danvar and a couple other cities had adopted to forbid discrimination in housing, hiring, and other practices based on sexual orientation. I supported that amendment, not so much because I bought into the “special rights” argument that amendment supporters invoked. I supported it because I thought such anti-discrimination laws meant the state “legitimized” and therefore implicitly recognized that being gay was acceptable. (For the record, the amendment passed and was overturned by the US Supreme Court 4 years later, the first of a string of decisions written by Justice Kennedy that led to Obergefell.)

My views then made up an almost textbook case of “bigoted position.” I can see that now. Perhaps unsurprisingly, I didn’t see that then. It took me a long time to change my mind on such issues.

The principal reasons I changed my mind were the following, in descending order of importance:

1. I noticed a pretty strong disjuncture between the Lockean idea of consent of the governed and the need for civil liberties with laws restricting gay rights.

2. As I grew up and from a variety of personal experiences and revelations, I came to have more empathy for gay persons.

3. Gay rights activists forced me to try to justify and rethink my position.

No. 3 was in last place for a reason, and in my opinion, was the least important for my conversion. My anti-gay views at the time certainly had a hearing at Cibolia State University, but it was a minority view there. I don’t think I ever voiced it, in part because the pro-gay rights position, as I heard it, was of the shaming sort, similar to what we find in Sam Wilkinson’s post Over There. It wasn’t uncommon to hear any objection to gay rights be answered with “why are you insecure about your sexuality?” or with a lecture about how Ancient Greeks thought homosexuality was good, so we should, too.

One thing the activists accomplished, however, was to compel me to justify, at least to myself, why I opposed gay rights. The stark reasons I mention in the first paragraph of this post solidified as my own answers to activists’ positions. As later events challenged and undermined those reasons, I began to see them as I see them now, as bigoted positions.

Perhaps my position would have changed sooner if the activists had tried to engage people like me more empathetically than they did. Perhaps not. But I realize that the goal of such activism isn’t necessarily to change my or anyone else’s mind or to honor my position on the matter. It could be to rally those who already agree, or to marginalize a certain position as bigoted or beyond the pale. In 1992, it was probably as much of a defensive posture as anything. Matthew Sheppard’s murder still hadn’t happened yet. And not only was Cibolia State University very close to where the murder would happen, it wasn’t a comfortable place to be gay or to support gay rights despite what seemed to me at the time to be the majority pro-gay rights view. There was one story of a person wearing a “straight but not narrow” button being physically assaulted, assuming I’m remembering things right.

Even now, in 2015, the righteous, crusading, vengeful tone we see in Sam’s post is probably not wholly about righteousness, crusading, and vengeance. It’s still probably not safe to be openly gay, regardless of what the Supreme Court says about the right to marry. Still, perhaps that tone ill serves the cause, as several on that thread, including Will and Mr. Blue from Hitcoffee, have tried to note there.

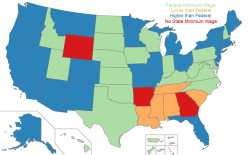

Maybe we don’t need to see St. Louis burn, because Puerto Rico already has:

The report cites one surprising problem: the federal minimum wage, which is at the same level in Puerto Rico as in the rest of the country, even though the economy there is so much weaker. There are probably some people who would like to work, but because of the sickly economy, businesses can’t afford to pay them the minimum wage.

Someone working full time for the minimum wage earns $15,080 a year, which isn’t that much less than the median income in Puerto Rico of $19,624.

The report also cites regulations and restrictions that make it difficult to set up new businesses and hire workers, although it’s difficult to know just how large an effect these rules might or might not have on the labor market.

A report by the New York Fed also suggests that Puerto Rico has a relatively large underground economy employing a big part of the population. These workers aren’t taxed or counted in formal employment numbers.

In any case, it’s relatively expensive to hire and pay workers in Puerto Rico, which along with the high cost of transportation, energy and other goods, means that fewer tourists are planning trips to Puerto Rico than they were a decade ago and the number of hotel beds is the same as it was four decades ago, according to Krueger and her colleagues.

This doesn’t speak to the appropriate minimum wage level in high-cost places like Los Angeles and Seattle, but it does point to the dangers of setting a national minimum wage with those places in mind and disregarding other places. Notably, the Washington Post itself downplayed the downside to the Puerto Rican minimum wage just a few months ago:

Based on that experience, Freeman thinks a few things might happen if the federal minimum goes up to $12. First, some companies might find ways to work around it, either by having their employees work off the clock or by turning them into independent contractors. That’s not ideal, but it at least allows people to keep collecting some paycheck.

“There are many ways that firms and workers will make sure that people don’t lose their jobs,” Freeman says. “If you say that 90 percent of the people get higher wages, and that’s what you want to have happen, and then 10 percent find ways to wiggle around so they keep their jobs, that’s a pretty good outcome.”

Second, if jobs do disappear, Freeman figures that people will move to areas of greater opportunity. “Minimum-wage workers tend to be young people, so they’re reasonably mobile,” he says. “Mississippi is the lowest-wage state in the country. If it tips you to move to Georgia, which has higher wages, that’s a reasonable response.”

Which, to me, involved a lot of handwaving away. I don’t mind people moving from Mississippi to Atlanta for the sake of greater economic opportunity. I don’t even mind bribing them to move if it’s better for the economy overall and better for their long-term prospects. But this isn’t really that. This is sort of handwaving damage done to the Mississippi economy in a “burning a village to save it” sort of capacity. And unnecessarily so, given the lack of portability of most minimum wage jobs. A lot of people won’t leave, and a lot of jobs will still need to be done. And allowing them to work for less – and allowing employers to pay less – is not a strike against the dignity of the worker, who can afford to live as well in Mississippi as someone with a higher minimum wage would be able to live in Atlanta.

But even setting aside the emigration question, there remains the question about those who stay behind. Which is the problem that Puerto Rico is facing now and the problem that Mississippi too would face. And could become a problem for a majority of the country. The $12 minimum wage nationally is analogous to the hike that occurred in Puerto Rico, to the point that the Washington Post felt comfortable pointing to it as a reason not to fear its repercussions.

Minimum wage advocate Arindrajit Dube is unmoved, however. There almost certainly is more to it than just the minimum wage. And perhaps the Krueger report is misguided entirely? The problems described therein, though, do seem real and precisely of the sort critics of the minimum wage have argued would occur.

Again, this isn’t an argument against raising the minimum wage – or even raising it aggressively in places – but it does suggest a degree of caution is warranted. Contrary to what I’ve heard some people say, raising the minimum wage to $12/hr (much less $15) is not bringing it in line with historical norms. It’s breaking new ground, at least over a dollar an hour highest than the highest minimum wage we’ve ever had (and which we had only briefly). That should be reason for concern, and Puerto Rico provides justification of proceeding with caution.

{Link via Oscar Gordon}

Sayeth the Transplanted Lawyer:

From where I sit, it’s fantastically obvious that anti-discrimination law at both the Federal and state levels ought to include rather than exclude sexual orientation as a protected class. We’ve protected sexual orientation by statute in California the same way we’ve protected race and sex and religion since 1992, with no apparent adverse consequences to either our economy or our citizens’ ability to enjoy religious freedom. Congress should pass ENDA. Further, Congress should amend Title VII to include sexual orientation as a protected status, and not rely on the courts to use questionable language and logic games to shoehorn “sexual orientation” into “sex” or “marital status.” If Congress does this, it can write in protections for religious freedom, and not have to rely on courts to do that, too.

This has happened already in Utah, whose body politic is dominated by no less conservative a religious institution as the Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter-Day Saints, found a way to reconcile itself with the inevitability of same-sex marriage. But bringing Republicans around to the notion that such a legislative scheme represents the best of all remaining possible worlds for social conservatives may take some work: it will require people of good faith who disliked the Obergefell ruling and see a need arising from it to protect religious liberties to accept that the perfect cannot be allowed to be the enemy of the good — and it will require people of good faith who, like me, rejoiced at Obergefell to concede that sincerely religious people are not going to give up their religious beliefs that same-sex marriages are strictly legal matters which their consciences forbid them from blessing.

It’s been interesting watching the “what next” debate light up on Twitter focusing around polygamy (goosed on by Freddie deBoer who openly advocates it, but mostly by conservatives who are itching to be able to say “I told you so”), when the more fertile ground really is, as Burt says, anti-discrimination law. Perhaps it’s because polygamy is simple to talk about, and a lot of people don’t even know that anti-gay discrimination is actually still legal. The dude in Tennessee probably thinks that his sign is okay because Freedom of Religion, when in fact it’s okay because of the absence of anti-discrimination law that most people probably assume is in place. Indeed, the whole debate in Indiana was built around the premise that their RFRA was allowing forbidden discrimination when said discrimination was not actually forbidden.

And even I have been wrong on this in the past. When I lived in Deseret, the legal counsel of my employer was fired when the company’s president discovered that he was gay. This came right after the rest of the staff had been let go. He was the one they felt could do the job of what used to be a department of three, but apparently only if he preferred the intimate company of women to that of men. And when this happened, I was really quite stunned to find out that it was perfectly legal according to Deseretian law. The company’s president didn’t even need to find an excuse. Gay? Fired. Even in Deseret, and even among my Mormon coworkers, the firing was largely seen as deeply unfair and wrong. The marijuana firings were understood and defended. Somebody may have defended the company’s right to do it (I can’t recall), but nobody defended the decision to.

And with this in mind, I was not surprised when Utah passed the law that Burt refers to. The LDS Church itself signed off on an employment-housing anti-discrimination law in Salt Lake County some time back. It’s going to be pretty hard to find prolonged, vocal opposition to those things. Except, that is, right after people are licking wounds after being slapped down in court and as some Republicans are looking for ways to retaliate. In the same way that the law in Utah was delayed by the ruling that allowed gay marriage, so too will anti-discrimination law. No matter, though, as I don’t expect it to take long.

One of the main reasons that Utah’s law passed is that it stuck to what mattered. My main concern will be the desire to, as Burt states, simply add sexual orientation to the protections offered on the basis of race or religion. That might be a desirable aim, but Utah would have no law right now if they’d insisted upon it. Maybe it should be illegal for Tennessee hardware guy to put up such a sign – it is certainly worthy of condemnation either way – but it also strikes me as not being nearly as fundamentally important as employment, housing, and other essential and emergency services. And for what it’s worth, the Human Rights Campaign agrees with me. As public attitudes change, as Burt and I both believe they will, we can revisit and simplify it.

When I bring this up, a lot of people are bothered by the symbolism of actively allowing discrimination in all but the most obvious of cases or, really, anywhere that we disallow discrimination against racial minorities. I understand the impulse, though I also see different situations as different (in the same way we allow certain gender discrimination where we don’t allow racial discrimination). But most importantly, we should not let our feels and symbolism trump things that will actually make lives better for gays and lesbians that live in states where complete non-discrimination just isn’t possible. Utah passed a law, and North Dakota was on the road to passing a law until the freakout over Indiana sent everybody running for cover. Progress can be made, state by state.

From here it is tempting to take it to the federal level and say “Screw North Dakota and the law we didn’t pass. We can make their law do what we want. Well, we certainly can, but I don’t think that’s particularly advisable. At least, not yet. Because there are things we can make them do and things we want them to do that we cannot make them do. Playing too firmly on the first set of issues makes progress on the second more difficult. We can make Tennessee Hardware Guy serve gays, but we cannot make him put out a sign that says “Proceeds from sales to gay customers will go to [anti-gay group].” Nor can we prevent them from putting up signs like the one that angered the lesbian couple in Canada to the point that they did not want to do business with that establishment.

Some things can’t wait for consensus. The rights and privileges of marriage were – at least arguably – among them. I firmly believe that anti-employment and anti-housing (including hotels and whatnot) discrimination are also among them. But at a certain point after that, I think it actually does more good for gays who live in Utah to have limited but locally supported protections than federally imposed ones that breed resentment. My calculus on this may change in the future (as it did – or came close to doing – on court-imposed SSM), but that’s where we are right now. Let’s get the essentials passed. And as minds and hearts change, further laws can be passed (or, even more optimistically, rendered unnecessary).

Aaron Warbled (who may be the commenter here known as Aaron David) expresses pleasant surprise over the tide turning on the Confederate Flag.

I am a little surprised about Graham, who turned an about-face over a couple of days. I’m less surprised about Rick Perry, who was involved in a similar – though slightly less contentious and high-profile – debate in Texas about fifteen years ago. And Mitt Romney, who I also mentioned, talked about his opposition to the flag while running in both 2008 and 2012.Perry and Graham are both politicians who have seriously stepped in it on racial issues over the years and are people whom I never thought would be coming around on this. And I know that the reasons for this might not be the purest, they might be simple political calculations. But if the political calculation of southern Republicans now includes rethinking that flag, well that means the wind is blowing strong.

I am not from the South and have no attachment to the area other than through my Father-in-law. That flag means nothing to me and is definitely not part of my history. For all intents and purposes I am a fourth generation Californian who was raised in a small coastal college town. A one high school town that was approximately 1% African American, making many of these issues very far away and academic as I was growing up. I am in my forty’s now, with a son of my own. As he goes to college in my hometown he remarks often how white the town is. And while I have many African American coworkers, I never realized how whitewashed my vision was. And that was a vision of this as far away and never ending.

And I am, to be honest, not very surprised about this at all. I won’t say that I knew it would happen, but from pretty early on I felt that the stars were aligned this time that it really actually could. First, because that’s where the murders occurred, but also because it’s an important primary state and I suspect virtually every important figure in the GOP had nightmares imagining a dozen candidates all pandering to South Carolinian pride at the expense of a general election viability. And for what? First, a series of states they’re virtually guaranteed to win in the general election. And second, and perhaps most important, the flag isn’t actually that popular in the South.

Most whites in the south are indifferent. In most states, its continued placement in such exaltation has been an indulgence of a small but loud contingent of the southern population, rather than an expression of popular sentiment. Further, over the last twenty-five years the class implications of the flag have become more noticeable, and you never want to be on the side of poorer people – even poorer whites – in a class struggle when they’re squaring off against wealthier whites (who may be even more opposed to the flag than black folks actually are). And when I saw that the South Carolina business community was involved, I knew it was probably over.

There just isn’t much percentage in it anymore.

It’s been a downhill roll since Governor Haley made her announcement. It’s taken an unfortunate detour to the private sector that means that it may exhaust itself before it gets to Mississippi, the other state under review. I say “unfortunate” reservedly. I’m actually glad that Walmart is taking it off the shelves. I sort of feel different about marketplaces like Amazon and eBay. Not because I want it to be easy for people to get a freshly-minted Confederate Flag, but because the policies sound so broad as to include anything containing the flag as well as legitimate historical artifacts. But my main issue is that it’s a distraction from related issues I consider more important: Mississippi, things named after confederate war leaders, and things along those lines.

Some have argued that this whole thing is a distraction from more pertinent issues related to the Charleston attack. I disagree. In part because I did view knocking the flagpole down as doable. A small, but significant and most importantly permanent change that can, over time, make more change possible.

Jon Rowe points to Eugene Volokh talking about whether we are a republic or a democracy:

Tom Van Dyke beat me to a lot of this in the comment section of Row’s post, but no reason not to slap my own words on our similar views of the subject. Different words mean different things to different people, but for me, at least, “We’re a republic and not a democracy” is a phrase that does have meaning, even if it doesn’t track 100% with the words themselves.To be sure, in addition to being a representative democracy, the United States is also a constitutional democracy, in which courts restrain in some measure the democratic will. And the United States is therefore also a constitutional republic. Indeed, the United States might be labeled a constitutional federal representative democracy. But where one word is used, with all the oversimplification that this necessary entails, “democracy” and “republic” both work. Indeed, since direct democracy — again, a government in which all or most laws are made by direct popular vote — would be impractical given the number and complexity of laws that pretty much any state or national government is expected to enact, it’s unsurprising that the qualifier “representative” would often be omitted. Practically speaking, representative democracy is the only democracy that’s around at any state or national level.

Specifically, it is an acknowledgement that democracy is intentionally limited here and there. Least controversially, by refusing to allow the majority to abridge the rights of the minority (though how we define abridged rights is subject to debate). And, as TVD mentions, we have purposefully disproportionate representation in one of our two houses, as well as in our presidential selection process.

People who say that there is no distinction between republic and democracy in the US, or that the US is both, are not necessarily wrong. They are, however, often using that as a springboard to point out the ways in which we’re “failing” to be democratic, be it through the existence of the Senate, the filibuster, the constraints on the government of the Constitution, or single-member districts. Irrespective of the merits of these anti-democratic or non-democratic mechanisms (I agree with some of the criticisms, and disagree with others), there is something circular about simultaneously saying that our system is democratic and then turning around and arguing that our system – even as intentionally designed – is failing at being democratic.

There are specific cases where our system wasn’t designed to be how it worked out. The Electoral College, for example, had one thing in mind and became something else. Single-member districts were intended, but gerrymandering wasn’t. The Filibuster as it currently exists is a later invention, though one agreed upon by the members elected in proportion to how it was designed (although elected directly now).

I have found it easier to sidestep the “a republic is a democracy” argument by adding a qualifier to “republic.” We are a constitutional republic. We are a federal republic. We are not, and never have been, and were never intended to be, a directly democratic republic. The idea of a straight (and sole) population-based legislative body was raised, and was rejected. And the “federal republic” part was absolutely intended, and is not (contrary to the perceptions of some) an anachronistic example of American exceptionalism. We are one of many federal republics throughout the world, and nowhere near alone in having disproportionate representation.

There seems to be a pattern in some of Blue America of testing the boundaries of liberal economic philosophy. In Connecticut, for example, they are testing the theory that states can ramp up taxation as much as they want and the anchor businesses will never leave. If they follow through, and GE and Aetna and others don’t leave, that will demonstrate that being “unfriendly to business” doesn’t actually account for much and corporations will house themselves mostly wherever they want to.

But nowhere is this being tested more than the minimum wage. Advocates of the minimum wage argue that raising the minimum wage doesn’t adversely affect employment. There is a fair amount of support for the notion that relatively small minimum wages don’t have too much effect. Of course, small minimum wages don’t help workers as much either. What about big minimum wage hikes? SeaTac recently shot theirs up significantly, and Seattle and Los Angeles have recently voted on it.

These cities aren’t the best test cases, though, because they’re not typical cities. SeaTac is home to an airport that cannot easily be relocated, and there are businesses around the airport whose business plan involves being right near an airport. Seattle and Los Angeles are among the most expensive cities in the country. So while a success there might inspire San Jose and New York City, they’d tell us less about what, say, Boise should do. Or, for that matter, the State of Washington which includes not just expensive Seattle but less expensive Spokane and a bunch of inexpensive cities in between. Critics are suggesting that the result will be a skyrocketing in rents (and other things) that will ultimately swallow any gains. Which may be true, but that’s a problem that tells us about land-scarce, property-scarce locations and less about whether rents would skyrocket in Boise or Spokane.

These cities aren’t the best test cases, though, because they’re not typical cities. SeaTac is home to an airport that cannot easily be relocated, and there are businesses around the airport whose business plan involves being right near an airport. Seattle and Los Angeles are among the most expensive cities in the country. So while a success there might inspire San Jose and New York City, they’d tell us less about what, say, Boise should do. Or, for that matter, the State of Washington which includes not just expensive Seattle but less expensive Spokane and a bunch of inexpensive cities in between. Critics are suggesting that the result will be a skyrocketing in rents (and other things) that will ultimately swallow any gains. Which may be true, but that’s a problem that tells us about land-scarce, property-scarce locations and less about whether rents would skyrocket in Boise or Spokane.

One of the interesting things about all of this to me is that Seattle is a done deal and Los Angeles almost is, and nobody is hedging. Both sides seem pretty sure that things will work out as they predict and are not – as I think I would be – talking up how these are special cases and while we can learn from it, it won’t be the definitive judgment on what Raising The Minimum Wage means. From my perspective, if things go along swimmingly, I will start being a lot more supportive of what other large cities should consider, and if it backfires, I will think maybe we need to scale back future minimum wage hikes at least in similar environments.

Not as interesting as it will be, it provides little indication to me over what we should do with the national minimum wage, which applies just as much to Toledo as it does Seattle. The national minimum should be a reflection on the needs of the least expensive parts of the country. More expensive states, counties, and cities can ratchet it up locally as needed. And so if it only ratchets in one direction, start low. Concerns of a “race to the bottom” don’t seem to apply as much when it comes to the minimum wage – which tends to be location-specific jobs – than other areas of labor law and regulation that might push a company to settle in Texas instead of Connecticut. (“Or maybe not,” says the Nutmeg State.)

But you know what would change my mind on a national minimum wage, and convince me that perhaps we can be aggressive when it comes up to moving it up nationally? It if were to succeed in a relatively low-cost state or city. Enter St. Louis:

St. Louis could be the next city to raise its minimum wage significantly, if Mayor Francis Slay has his way.

Slay spokeswoman Maggie Crane on Tuesday confirmed that the Democratic mayor wants to raise the city’s minimum. A starting point for discussion is $15 per hour by Jan. 1, 2020, Crane said, but details are still being ironed out.

And Kansas City…

A proposal working its way through the Kansas City Council would raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour within the city by 2021.

On Wednesday, the council’s Planning, Zoning and Economic Development Committee is expected to consider Ordinance No. 150271, a proposal that would raise the minimum wage to $10 an hour by September 2015 and, starting in 2017, gradually increase it to $15 an hour. Councilman Jermaine Reed proposed the “living wage” ordinance.

Neither of these two cities are bursting at the seems in terms of population or population growth. Fifteen dollars an hour in either of these cities would be absolutely huge. And if it were not to call a wave of unemployment, it would change how I see the minimum wage. I wouldn’t necessarily sign on to a $15/hr national minimum wage, but I’d look at $12 with quite a bit less trepidation and wouldn’t worry so much about the Puerto Rico example. My belief is that raising the minimum wage would not be a good idea for any of these cities. But man, if I’m wrong about that… man.

Neither of these two cities are bursting at the seems in terms of population or population growth. Fifteen dollars an hour in either of these cities would be absolutely huge. And if it were not to call a wave of unemployment, it would change how I see the minimum wage. I wouldn’t necessarily sign on to a $15/hr national minimum wage, but I’d look at $12 with quite a bit less trepidation and wouldn’t worry so much about the Puerto Rico example. My belief is that raising the minimum wage would not be a good idea for any of these cities. But man, if I’m wrong about that… man.

It could be, though, that we’ll not find out. First, it’s not entirely clear that state law allows for it. The St. Louis mayor is preparing his legal argument, but this could be little more than legal grandstanding. And if there is any ambiguity in the state law – and there doesn’t seem to be – the state legislature amended a bill banning the banning of plastic bags to prevent locations from raising the minimum wage. Which the governor may veto, but there is nearly a veto-proof majority.

Which, on the one hand, I think is probably good for Kansas City and St. Louis and by extension good for the state that relies on those two cities as anchors. On the other hand, the ratchet. While I would question the wisdom of raising the minimum wage, it seems to me that it’s the sort of mistake that cities should be allowed to make. In order to allow podunk, Missouri to preserve its more modest minimum wage, other parts of the state should be allowed to raise it. I am not a firm believer in local control over all things, but I do think it applies here where local needs can differ so greatly from one place to the next.

Which is perhaps more valorous than the other reason, which is that it might be helpful to watch St. Louis burn without putting the rest of the country at risk.

In may of 2011, I wrote the following on Facebook:

Michael Barone writes that Mitt Romney should not be considered the front-runner (link at bottom). I actually agree. He’s not substantively ahead in the polls (and is behind in many of them) and you shouldn’t call someone a front-runner unless they’re in the lead. But he remains the likely nominee. Barone’s writing, rather than refuting this point, actually supports it to an extent. He says that there are “only six” cases of the “next-in-line” (NIL) getting the nomination since the primary model was deployed in the 70’s, but that constitutes every non-incumbent nominee since the primary model was deployed in the 1970’s. There is not a single counter-example.

There are, as Barone points out, a number of “almost” counterexamples (Reagan in ’76, Alexander in ’96), but they remain “almosts” for a reason. It didn’t happen. The fact that the NIL nominee’s nomination was in doubt through the primary season actually supports the likelihood of a Romney nomination. Why? Because the second strongest argument against Romney’s nomination is that people aren’t really excited about him. But as past performance indicates, it doesn’t really matter. The next strongest argument is that Romney did something in Massachusetts that is very unpopular with GOP voters. This is the same party that nominated John McCain. Doesn’t matter.

I actually overstate my case somewhat. If a really strong candidate were to come forward, I don’t doubt that Romney could be unseated. In fact, if Huckabee runs, Romney shares the NIL title (though I think his establishment support will probably put him on top). But no candidate really comes to mind. All of them have substantial drawbacks. We’re likely seeing a replay of 2008, where all of the candidates have something that makes them “unacceptable” for some reason or another. The odd thing about 2008 was that it was full of candidates that I just couldn’t see winning the nomination. But one of them had to. The odder thing is that 2012 seems to be the exact same issue.

Absent Huckabee or a really strong candidate (no names come to mind, and I know a lot of names) entering, the only other way I see Romney losing is if it’s essentially a two-man race between Romney and Pawlenty. Pawlenty is not sufficiently exciting that he will stand out from a pack of candidates, but if voters are essentially given two choices, and one of them is the guy that ran the dry-run for Obamacare, I could see Pawlenty getting the nod. But that depends on a dearth of new candidates and a lack of traction among the people already running.

It’s a longshot. I say this as someone that is somewhat lukewarm about Romney and will likely support Pawlenty (or Daniels, if he runs). On the other hand, if Romney does pull out the nomination, I don’t think that the lack of enthusiasm for him (same goes for Pawlenty) means that he can’t win. John Kerry almost won, after all. As long as the GOP nominee meets a general threshold (which Romney, Pawlenty, Daniels, and Huckabee would all meet), the 2012 election will be a referendum on Obama more than anything else.

Photo by DonkeyHotey

Dave Schuler believes that, without a doubt, that George H Bush is our greatest living former president. A poll from last summer just about agrees, giving Bill Clinton higher approval but also higher disapproval. I am inclined to agree as well.

Dave Schuler believes that, without a doubt, that George H Bush is our greatest living former president. A poll from last summer just about agrees, giving Bill Clinton higher approval but also higher disapproval. I am inclined to agree as well.

Bush the Elder is getting more elderly. He turns 91 in a few months. Reagan and Ford lived to be 93, so he’s not exactly living on borrowed time. But he’s not looking really good, either.

In case you may not be away, his son Jeb is all-but-running for president. I am, personally, rather bearish on Jeb’s odds of becoming president. I am honestly not that bullish on his odds of even getting the Republican nomination. I know, I know, the GOP always dates the radicals and marries the establishmentarian, but this time feels different. More or less from the moment Huckabee announced he wasn’t going to run in 2012, I believed the nomination was Romney’s. I don’t feel that way about Jeb. He seems extremely out of touch about how out of touch he is with the party. He’s just proven to be a lackluster candidate so far, and this time around there are other options. I think he has a better chance than any other individual candidate, but if I were betting for or against him, I’d bet (lightly) against him.

Unless, that is, his father dies sometime between now and then. Which gets me to the point of this post. His father is somebody that it’s become kind of hard to say much negative about, generally speaking. Republicans see him as one of their own and from the Reagan era at that. Democrats see him as fundamentally different from the current lot of Republicans. It’s considered poor taste to speak ill of the just dead, but I think there will be less tongue-biting.

Unless, that is, his father dies sometime between now and then. Which gets me to the point of this post. His father is somebody that it’s become kind of hard to say much negative about, generally speaking. Republicans see him as one of their own and from the Reagan era at that. Democrats see him as fundamentally different from the current lot of Republicans. It’s considered poor taste to speak ill of the just dead, but I think there will be less tongue-biting.

Which makes his father’s death, if it occurs between now and next November, a potentially important thing.

If it occurs during primary season, it could really give Jeb a boost. He may only need a boost. Just a bit of separation between him and everybody else. Rubio’s funding could then dry up. People looking for alternatives may stop looking. Then we may see a 1-on-1 race between Jeb and Walker or Jeb and Perry with the full weight of the Republican establishment squarely behind the son of the fallen hero.

If that doesn’t happen, and if Jeb wins the nomination, it could be salient in the general election, too. It’s become fashionable to view voters as these immovable objects who don’t respond to anything, but I don’t think that’s particularly true. There may not be as many independents and swing voters as there used to be, but they exist, they exist right on the margin, and their vote counts twice if they switch (-1 for the person they’re switching from, and +1 for the person they’re switching to). If it’s close, and it could be, it could help Jeb. Not only because Bush the Elder is his father, but because one of Jeb’s faults is that it feels like he’s running a 90’s campaign on the teen decade and though he physically takes after his mother, there does seem to be more of his father in him than there was in George W. It could also help reorient “The Bush Connection” away from the most unpopular living former president towards the least unpopular recently living president.