Monthly Archives: February 2015

Freddie deBoer argues that “pedantic ridicule never convinced anybody of anything.” Ethan Gach made a good counterpoint that the “tactic is actually extremely effective against those who do share cultural affinities and social ambitions.” I’d bridge this gap by saying that the latter group will, at least, pretend to be convinced and argue it going forward. Which may amount to the same thing.

Freddie deBoer argues that “pedantic ridicule never convinced anybody of anything.” Ethan Gach made a good counterpoint that the “tactic is actually extremely effective against those who do share cultural affinities and social ambitions.” I’d bridge this gap by saying that the latter group will, at least, pretend to be convinced and argue it going forward. Which may amount to the same thing.

Uncle Steve argues that Hollywood may be less liberal and egalitarian than it thinks.

Strangely enough, as building commences, rent in DC has fallen more than most other major cities.

Purple City has a post about edge cities, looking at Chicago and Houston (which, by the way, is very large). An eye-opening tidbit in the second part, the reverse commute in Houston (people starting in town and driving to the suburbs for work) is worse than the traditional commute inside the city’s loop.

Rose Eveleth argues that free access to science research has its problems. BioMickWatson disagrees.

How the US oil industry is poised to come out a winner in collapsing oil prices, while Russia looks the loser. That might not be the easiest sell to North Dakotans if they get laid off.

A lot of elite investment firms and the like wouldn’t hire a Super Bowl hero.

The UK has given the go-ahead to DNA-spliced three-parent children.

In graphical form… how vaccines prevent measles outbreaks. It shows transmission rates at various vaccination rates. Pretty cool.

North Dakota has been invaded by monster-sized jackrabbits. I’d say that the University of North Dakota (formerly the Fighting Sioux) has their new mascot, but it’s already taken by South Dakota State.

H1B visas are supposed to go to jobs that can’t be filled by Americans, but some employees of Southern California Edison are irate because they’re having to train their H1B replacements.

This is one bad-arse archer.

Haruki Murakami has an advice column, and now there are English translations.

A doctor in Massachusetts is no longer accepting patients that are obese. Or any patients over 200 pounds, apparently.

I have no comparable item by someone else to link to. So… Megan McArdle gave the following Valentine’s Day advice to women who were waiting for their boyfriend’s to propose:

So here’s my message to those ladies: It’s time to let go. I know, I know — it feels catastrophic to think about ending a relationship that you’ve already invested several years in, when what you want most in the world is for that relationship to continue until one of you gets carried out feet first. But take it from me, it will feel even more catastrophic after you’ve invested several more years. If you’re in your 30s, both of you already pretty much know who you are. And after a couple of years, you also know whether this is someone you want to spend your life with. You’re not going to get any new information by sticking around — except “My God, I wasted five years on this man.”

As you may guess from the prior paragraph, I speak from personal experience. I invested almost four years in an almost-great relationship that ended with me, shattered and tear-stained, deciding to pick up and move to Washington. You can hear all about it in this NPR segment from a few months back, which they re-aired this morning. Or you can read about it in my book, where I delve into even more of the gory details and deftly weave it together with the sad saga of GM’s decline, which happened for much the same reasons that my failed relationship did.

“Seriously?” you’re asking. “Love is like … automobile manufacturing?” Well, no. But companies are composed of people. And people tend to make the same sort of mistakes over and over. This particular mistake is so common that economists have a name for it: the sunk cost fallacy.

I have myself been on the other side of that equation. Well, sort of. Most of my college years were spent dating Julia. The end result of over four years of dating was… heartbreak. The break up came tangentially over the question of marriage. It wasn’t quite of the cloth that McArdle refers to, but it dealt with similar issues of undercommitment and overcommitment. We’d been dating for over four years and it was time to enter the next phase. This was not the result of pressure on her part, but I did feel it was imminent. Dutifully, I started making plans to propose. And it was in the process of said preparations that I started feeling an grinding sense of dread. Which was odd, because as far as I knew I wasn’t unhappy. Why would I respond this way? It turned out that the answer was that even though I was happy, I was no longer emotionally committed. She, on the other hand, very much was. That much was evident.

I didn’t quite get to pick when to pull the pin on the grenade. Julia had made a comment that all but demanded words of commitment that I simply couldn’t deliver. In retrospect, that she said what she said at all was demonstrative that she knew there was something wrong. An inadvertent admission of insecurity, which I could do nothing but verify the validity of. It didn’t end right then and there. She begged, pleaded, and sent our mutual friend Tony to try to talk me out of the insanity. Instead, Tony went back to her and reported that whether discussions were ongoing or not, the relationship was over. That was what she needed to accept it, and gave up.

It turned out to be a happier ending for her than for myself. I involved myself with someone who was everything that Julia wasn’t and in all of the wrong ways. Julia, on the other hand, was embarked on a relationship with Tony within a month.

Her relationship with Tony also lasted four years and it followed the map that McArdle lays out a little more closely. Whereas between Julia and myself, it was not realistic to expect me to propose after a couple of years (we were 20!), it was around that time when she started waiting for the wedding ring. They were cohabitating by that point, and shared a dog. Tony was long getting over a divorce from his first wife and was disillusioned about the institution of marriage. Julia had nothing to do with that failed marriage, though, and in her mind was being penalized for it. Julia started pushing, he started pushing back. And everything fell apart when it became clear that he wasn’t going to marry her and she wasn’t going to be happy with that. he was ultimately the one who left, but only because he was the one who could see with clear eyes that the problems couldn’t be reconciled.

There are more stories I could tell, mostly following the same trajectory. My brother, my best friend from childhood. Years invested, and lost in that investment. Typically, he ends it either by walking away or doing something which all but forces her to do the same. Though I know the opposite is possible and am sure it does happen, the gender roles are actually pretty constant. To avoid reducing it to “him” and “her” I’ll go with OCP and UCP for overcommitted partner and undercommitted partner.

Sometimes, it’s precisely the Moment of Truth – the contemplation of marriation – wherein the distinction between levels of commitment start becoming more apparent. The UCP will often come up with excuses (to their partner, to themselves) for their hesitance. For my brother and I, it was about saving the money for a wedding ring. For Tony, it was about “the institution of marriage” (he was remarried – to his ex-wife, no less – within six months of his split with Julia). But as you contemplate it, and as the pressure increases, it can really grind away at you. In the comfort of a stable relationship, it can be easy to put it aside indefinitely until confronted with The Question (needing to ask it).

But once the asymmetrical commitment becomes apparent, if it’s not resolved quickly, I’m not sure I have ever seen it resolved in a happy manner. Or maybe I have, but only when it’s a very specific issue that needs to be confronted (such as whether to have children, or where to live) and the OCP bites the bullet. But it’s rare, and it’s fraught with peril. But the more that has been invested, the more difficult it can be to walk away. To admit failure. To absorb the sunk costs.

Which brings me to this next video:

In one sense, the video may come across as being on the opposite side as McArdle, if it’s tackling the same subject matter at all. The video advocates commitment-caution, whereas McArdle is talking about leaving due to insufficient commitment. Where the two tie together, though, is the degree of commitment prior to marriage. Taking on costs that, later, could be sunk. Erecting barriers to exit so that in the event that the relationship is not progressing as quickly as you need it to, you become reluctant to leave. Adding to the costs, both literal and opportunity. Sometimes money, always time.

It is often perceived that premarital cohabitation is a sensible intermediate step in between light courtship and marriage, but the statistics have never really bore that out. At best, controlling for as many factors as possible, it’s pretty much a wash. For every disastrous marriage averted by discovering the problems by living together or having a joint pet or joint bank account, there seems to be another case (or more than a case) of a couple who might have rightfully broken up but don’t because they’ve slid into the lock. Cohabitation seems to work not when it is used as a filter to marriage, but when it is between a couple that has already decided to get married and/or otherwise meet the criteria for a successful marriage (not too young, upbringing, etc.) And that doesn’t really account for cases like Julia and Tony, where perhaps divorce was averted but a significant amount of time was lost.

Every couple is different, of course. As the video points out, however, we can often back into commitments we don’t realize we’re making, or thinking that we’re making prudently because it’s Still Not Marriage. It’s an inconsistent caution.

Apart from the religious aspects, the legal aspects, and the romantic aspects, the crucial role I believe that marriage can play in our lives is forcing a degree of honesty about what our intentions are. Honesty with others, and honesty with ourselves. “Will you marry me?” may sound more romantic than “Are you willing to enter a formal entanglement that will make separation more difficult?” But the question is there whether we consciously dive in with a ring and an answer, or whether we go into the pool one step at a time until we are just about as wet.

Marriage or no marriage, it’s extremely important to recognize what, specifically, you are after in a relationship. If it’s just to have fun and bide your time until later in life when you’re ready to get married, that’s cool. But if it’s marriage you have in mind, or it’s marriage that your partner has in mind, it’s quite important in my view to keep your eye on the ball. To be able to ask yourself, and them, if it’s not happening why it is not happening. In terms of commitment, there’s no substitute for marriage. And in its unwelcome absence, that empty space should be scrutinized.

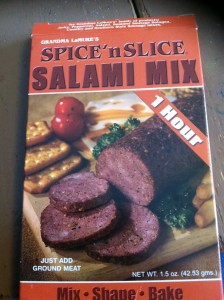

I took a trip to Cabela’s today to look for hiking pants for my daughter before we head to Belize. No luck. We did have a chance to eat elk burgers, though, and then I found this, and thought, heck, yeah, I have to try that.

It recommends 2 pounds of ground beef, venison, turkey, moose, elk, or pork. I interprtehh”kd the “or” as “and,” and in the absence of any wild game mixed a pound each of ground beef and pork together. Together they make excellent meatballs for spaghetti, and salami, spaghetti, it’s all Italian so it has to work, right?

The directions also suggest “adding olive, peppers or other ingredients.” Will do! Scrounging in the fridge I found olives, and capers seemed like a must-do (capers are always a must-do in our house), and sun-dried tomatoes seemed like a good idea, too, but before I found those I scrounged out some sun-dried tomato pesto, and a light bulb went on in my head (but not in my fridge, which has been light bulbless for years, making scrounging more adventurous) that said “even better!”

Everything mixed together with the spices from the packet, and then I hit a small stumbling block–I don’t have a proper baking rack. Well, if this works out well, I’ll get one next time, and meanwhile I’ll just cook it on the big rack in the oven (hoping the meat doesn’t break up and fall through).

Results! That is some seriously strong salami. I like it, but I couldn’t eat more than a sandwich of it at a time. The kids like it, but my wife doesn’t. It’s obviously not going to get eaten quickly, though, so I put half in the freezer for later use. And maybe we’ll have salami sandwiches for dinner sometime this week.

Overall, even if it doesn’t all get eaten, it was worth the ten dollars or so to have actually made my own salami once. And with the spice ingredients listed on the package, I could try mixing my own spices sometime if I want to delve deeper into salami-making.

Sporting events are sub-optimally suspenseful, according to new economic research.

In the context of a mystery novel, these dynamics imply the following familiar plot structure. At each point in the book, the readers thinks that the weight of evidence suggests that the protagonist accused of murder is either guilty or innocent. But in any given chapter, there is a chance of a plot twist that reverses the reader’s beliefs. As the book continues along, plot twists become less likely but more dramatic.

In the context of sports, our results imply that most existing rules cannot be suspense-optimal. In soccer, for example, the probability that the leading team will win depends not only on the period of the game but also on whether it is a tight game or a blowout…

Optimal dynamics could be induced by the following set of rules. We declare the winner to be the last team to score. Moreover, scoring becomes more difficult as the game progresses (e.g., the goal shrinks over time). The former ensures that uncertainty declines over time while the latter generates a decreasing arrival rate of plot twists. (In this context, plot twists are lead changes.)

However in the context of the NBA’s playoff scheduling, “there is an equal amount of suspense and surprise in the 2-3-2 format of the NBA Finals … as in the 2-2-1-1-1 format of the earlier NBA playo rounds.” And in presidential primaries it doesn’t matter what order states go in–you can’t increase suspense by having smaller or more partisan states go first (a counter-intuitive finding, but they’ve got a mathematical proof that’s over my head, so it has to be true).

Hat tip to Marginal Revolution.

Are there aliens behind our currency?

Vice writes about how attempts to Uberize and Airbnb New Orleans is running into a cultural wall in New Orleans. Notably, a friend of mine who lives there and is a free marketeer in most respect hates Airbnb.

Mosaic writes about the precarious state of modern Judaism in the United States.

I don’t completely agree with the complaint here. If you want people to stop using your image for commercial purposes, you can do that. But failing to do that, it seems weird to say “We don’t mind people using our image for commercial purposes, as long as it’s not the people hosting our image.” This explanation helps a little, but not much. Still mulling it over.

Oilman or Cowboy? The oil boom is enticing more people to the former, creating a shortage of the latter. Or will the price cut solve the problem?

I’ve mentioned before that Texas is one of the few states even if you account for college cost inflation (Illinois and North Dakota being two others), that spend more on higher education than it did in 1987. Perhaps as a result, Texas A&M just swiped the University of Washington’s president.

Jailbreak! Some women in Brazil escape from prison by fooling guards into thinking that there is a mass orgy in their future.

Carnell Alexander has a warrant out for his arrest for being a deadbeat dad, for a child that isn’t his. Michigan does not have a paternity fraud (or mistaken paternity) law to protect non-fathers. The topic is up for debate in Washington state.

If you want the police to check up on a relative after they’ve had surgery, that might not be a good idea.

If you kill a classmate, taking a selfie with the corpse is a bad idea.

There’s something especially cool about buying a car with 900,000 miles on it.

Michael Booth argues that the Nordic nations are not utopias. They do stand to be the losers of the low oil prices.

Michael Brendan Dougherty takes on the role of mansplainer. {More}

Is political correctness a creativity-booster?

When I grew up, there were three giants of network news: Dan Rather, Tom Brokaw, and Peter Jennings. Each had held their job for over twenty years. I took for granted each election that I would turn on the television, and there they would be. When they stepped down (well, Jennings died), it was a pretty big deal about who would replace them. Charles Gibson, Katie Couric, and Brian Williams.

Gibson retired in 2009, Couric left in 2011, and it looks like Brian Williams is out (even if it’s technically a suspension). Brian Williams always struck me as the most lightweight of the three, and I don’t understand how he got the job when Stone Phillips was available. But to me, only Gibson had the “it” that I thought the Big Three (and, for that matter, Ted Koppel) had. Diane Sawyer, who replaced Gibson and who is also now gone, also had it.

I haven’t seen Sawyer’s successor, or Couric’s, for that matter. With the proliferation of cable news, I suppose it just doesn’t matter as much as it used to.

I previously likened this to the big annual Disney release. When I was a kid, it was always a big event what movie Disney would do next. Then along came Pixar and and the proliferation of media, and Disney movies came and went and just didn’t matter so much.

And with the proliferation of news outlets, Brian Williams getting suspended for six months is eclipsed by the host of a comedy and new parody show leaving.

I don’t know if this says more about the evolving business of news, our current culture, or that at some point the nakedness of the emperor just became a bit more obvious.

Business Insider has a list of the most underrated colleges in America. It’s essentially a comparison of graduate wages beside USNWR ratings and looking at the outliers. It’s a crude methodology, but illuminating all of the same.

The most obvious thing is the frequent appearance of technical schools. The New Jersey Institute of Technology is #1, Missour S&T is #5, Louisiana Tech is #8, Illinois Institute of Technology is #12, and Michigan Tech is #15 (with privates Clarkston and Stephens also up there). This is unsurprising, given the givens. I’m a little surprised not to see South Dakota School of Mines on the list, given that not long ago their graduates were outearning Harvard’s. Colorado School of Mines is there, though.

Land Grant universities are also represented from Arizona, Oregon, Washington, New Jersey, Virginia, Arkansas, Alabama, Utah, and Idaho. Notably, there are no state flagship universities on the list, excluding those that are also the land grants.

The University of Alabama at Huntsville is #10. UAH comes up when we talk about athletics programs. They’re a notably good one that doesn’t have any football program to speak of. Maybe they wouldn’t be so unrecognized if they fielded a football team.

Some, like UAH, Texas Tech, and Houston are aided by their proximity to economically hot areas, but that doesn’t seem to help the Dakota schools. And Michigan Tech is on the list, so there are limits to that theory.

So Will admits he tried to bait me into writing about this prof at Marquette U. who’s been blogging about the school, which has now announced they’re revoking his tenure and firing him, which has him claiming they’re violating his academic freedom. Here‘s the prof’s side of the story. In a nutshell, an undergraduate student complained about a graduate student instructor, this prof (from a different department) blogged about it, and the solid waste struck the spinning blades. Will asked my thoughts, a subtle hint that went right over my head as I replied to him via email. Here’s what I wrote.

_____________

Well, he’s a political science prof, so I say fire him.

More seriously, this looks like a case of everyone behaving badly.

1. The graduate student instructor didn’t handle the discussion well. Although despite her being a feminist vegan philosopher, which means I’d probably have extensive disagreements with her, I’m sympathetic because it takes time to learn how to manage students well–after about 14 years I still feel like I’m learning that.

2. The undergrad student is badly mistaken if he thinks he has a right to class discussion on his pet issue.

3. I think the blogger prof is incorrect to call his blog an issue of academic freedom. Not everything we say comes under academic freedom just because we’re academics. For some people that becomes a nice coverall for everything they want to do, without restraint. That doesn’t mean I think there’s necessarily anything wrong with the prof blogging about these things.

4. The Arts & Sciences Dean is probably violating the University’s own policy, as seen in point c here:

“When he/she speaks or writes as a citizen, he/she should be free from institutional censorship or discipline.”

But if the prof is not speaking as a citizen, but as a member of the University, then academic freedom probably does apply.

Marquette is of course private, so it has greater freedom of action here than a public university might, and I don’t find that it has a faculty union (although it might, and I just can’t find a note of it), which would mean the blogger prof has less of a leg to stand on.

For my part, I find it unwise to blog too openly about what happens in my place of work. Some faculty get pretty arrogant and think they’re untouchable and any repercussions for what they say about their place of employment are totally illegitimate. I can’t really speak to the issue of legitimacy of repercussions, but I know from observation that legitimate or not, repercussions do happen, and people who act like they’re immune are idiotic, or, to put it more nicely, un-strategic.

___________________

To add just a bit more, academic freedom is intended to allow people the freedom to research controversial issues, and argue for controversial findings/interpretations of those issues, without repercussions, so we don’t stunt the search for knowledge. Its purpose is not to allow us to criticize our employers (although of course protection for that is nice as well, just for a different set of reasons).

Nor, I think, is academic freedom intended to protect people for any particular political stances they want to yammer about publicly. The University of Illinois, for example, did not, in my opinion, violate the academic freedom of Steven Salaita. But being a public university, bound by the First Amendment, they arguably violated his free speech rights.

And yet I have a hard time imagining the same uproar had Illinois rescinded the hiring of an academic who tweeted that gangbangers were responsible for white racism, as Salaita tweeted that Zionists were responsible for anti-semitism. Defenses of speech and academic freedom are sometimes selective. My graduate program once counted political activity towards tenure, until someone asked what they’d do if they had a politically active white supremacist in the department. That crystallized the reality that it wasn’t really political activism they approved of, but the correct type of political activism, even if those bounds were rather wide.

There’s often a fine line between political activism and academic activity. As an academic I’m persuaded that its foolish for governments to grant rents to firms, but if I stand up at a city council meeting and oppose a tax credit to lure a business to town, is that academic or political? What about if a geologist talks publicly for/against fracking? Perhaps the obscurity of the line is what leads academics to think that any pronouncement they make is covered by academic freedom. And in the Marquette prof’s case, I’m not seeing that journalism, as the professor (correctly) notes he’s doing, about the university itself, counts as academic freedom for a political scientist.*

Whatever the cause, I think we ought to be more humble about how we extend the concept of academic freedom. The step from research findings to applications is so fraught with problems, and with such a history of failure (in all disciplines), that I think we ought to view application, or at least public argument for application, as something distinct from the freedom to research something. Those arguments ought nevertheless be covered by freedom of speech, for those faculty who work at public universities. And private universities would probably be well-served to privately extend a guarantee of freedom of speech as well. But they don’t have to.

__________

*Our faculty union contract with our private college explicitly states that we have academic freedom concerning things in our area of specialty. The Art Historian who makes pronouncements about global warming? That’s not necessarily covered, and I’m not sure it should be. If academic freedom is designed to allow us to learn more about controversial issues, it doesn’t seem intended to protect us in talking out of our asses about things we haven’t actually studied at all.

I was actually discussing this with someone recently, but if you want your kid to get ahead, don’t teach them Manderin but instead plain ole Spanish.

I was actually discussing this with someone recently, but if you want your kid to get ahead, don’t teach them Manderin but instead plain ole Spanish.

Alex Suskind writes on the enduring legacy of Cowboy Bebop. I don’t rewatch nearly as much of my old anime as I’d like, but I find myself rewatching Cowboy Bebop every few years.

Last summer, Scott Alexander reviewed Elizabeth Warren’s Two-Income Trap.

China has opened a Hogwarts! For art students.

Jeannie Suk is concerned that future lawyers are not being trained to understand rape law because of student sensitivity. Corey Yung isn’t seeing it, though. Non-lawyer Conor Friedersdorf also comments on the issue.

Yes! Our experiment in trying to get everybody out of bed earlier has been an abject failure.

California Sunday magazine has an in-depth look at the 43 Mexican students who went missing, and the change that may occur because of it.

About dang time. The pickings for Android car stereos have remained too slim for too long.

Alex Tabarrok writes about three felonies a day and its ramifications.

Even after a global apolocalypse, people gotta eat.

As Gabriel Rossman says, “Grant us this day our daily pageviews and forgive us our outrages as we forgive those who outrage against us.”

News is that e-cigarettes are less addictive than combustibles, Sally Satel argues that anti-smoking groups should endorse Snus and E-Cigarettes. The Snus thing is interesting, because both sides cite it without hesitation as proof on the potential dangers and potential of ecigarettes.

Here’s a story from 2006: A woman was applying for aid and was denied because the maternity test said that she wasn’t her child’s mother.

Jailed criminals think pretty highly of themselves.

Let me state upfront. Civility should never be a standard for freedom of speech. The state should not punish people for engaging in “uncivil” speech and those who engage in “uncivil” speech deserve the protection of the law. If there are any exceptions I can’t think of them right now.

Let me also state upfront. It was wrong for the U of I system to “non-hire” Steven Salaita for the incivility of his tweets, etc. It was wrong on procedural grounds. An excellent case is to be made that when the department invited him “pending approval of the Board of Trustees,” that approval was intended to be pro forma. It was also wrong because the U of I system is a public institution, and a public institution ought to have a darn good reason when it discriminates against a prospective employee’s speech without a showing that that prospect’s speech would negatively affect his or her job performance. And the Board of Trustees, as far as I know, made no finding that Mr. Salaita’s incivility would affect his teaching. If I am wrong, please provide me evidence and if the evidence is compelling, I’ll revise my objection as to the Board’s finding but probably not to the procedural grounds.

But with that out of the way, when it comes to academic speech civility can be a legitimate restriction.

Most university professors play three roles. They teach. They participate in shared governance, such as committee work. And they perform scholarship through publishing, giving public lectures, participating at conferences, authoring blogs, making themselves available for interviews on documentaries, and doing other things.

In that last role, when they speak they are speaking ex academia. When they speak ex academia, they speak from within the bounds set by their institution, by members of their department, and by members of their discipline, such as those who edit and referee the journals, create conferences, and comment on public statements made in the general area of their discipline.

Those “bounds” or standards are many and they evolve over time. A historian today who states that antebellum slaves in the United States were basically happy and loved and were well-served by their masters is transgressing a pretty solid boundary. If that historian makes such an argument and hasn’t the evidence to back it up or doesn’t at least make the necessary qualifications about the nature of slavery or the difficulties of the type of evidence that is available, he or she will be shunned out of what is considered acceptable for the profession.

If that person is an emeritus/a, they* might be smiled at as a crank or curmudgeon. If that person is a tenured professor, they might find themselves invited to or accepted by fewer journals or conferences. If that person is a tenure-track scholar and their argument about slavery is pretty much the sum total of all they’re about when they speak ex academia, they may very well be denied tenure unless they’re a superstar (or at least hardworking and willing) teacher or the “committee martyr” type that seems to exist in medium- to large-sized academic departments. If that person is a junior scholar, he or she will have a pretty hard time getting hired. The departments will take that speech into account, especially if speaking ex academia is a big part of the job.

That particular “standard” is not a civility standard. It’s also not a firm standard. But it is a standard nonetheless. The literature on the essential violence that was chattel slavery in the U.S. is so broadly accepted that at the very least anyone who claims there were some benefits for the slaves (such as Fogel and Engerman, whose book I have not read but about which there is a Wikipedia article here) must acknowledge it and either (unlikely) refute it or (more likely) find certain benefits that coexisted with the violence.

That example risks violating an American version of Godwin’s Law. And to be clear, I think an outright denial of the essential violence of slavery is akin to the outright denial of the scale of mass-murder executed by any mid-twentieth century despot. And to be further clear, I also realize that such a case is a marginal one. But my goal is only (or mostly) to demonstrate that a standard exists and legitimately so. And I don’t think many will disagree in the abstract. And if they do, I’d concede that disagreeing in the abstract about even such propositions often falls in within the bounds set by any given discipline.

But enough meta. What does this have to do with civility? This: It’s possible that enough members of a discipline can decide on certain standards of argumentation deemed acceptable for speaking ex academia that invoke something like treating interlocutors with respect and evincing a respectful attitude toward, say, humans as humans. It’s possible that departments or even entire institutions can make such a standard applicable to judging one’s statements when made ex academia.

Would an academic journal be acting legitimately within its discipline if it declined to publish anything that relied mostly on ad hominem attacks against other scholars? I believe it could. Would an academic department be acting legitimately within its discipline if it declined to hire a controversial person because that person, in the judgment of those who ran the department, engages in uncivil speech? I believe it could. Would a university, in judging the scholarship of a professor applying for tenure, be acting legitimately by considering that professor’s argumentation against the norms of the discipline in which he/she works? I believe it could.

(For the record, I have read at least a smattering of journal articles that seem to be based on ad hominem argumentation. And one way to conceive of the whole “postmodern” approach to academic discussions is as an argument that ad hominems are valid. Maybe ad hominems are not per se “uncivil,” but attacking the background and good faith of one’s discussant at least edges toward the border of civility.)

I should state that as a practical matter, judgments of civility and incivility should err on the side of speech. It’s better to leave such determinations to the departments that have to work with whomever they hire. (Again, that’s as a practical matter. I don’t concede that academic departments are necessarily any fairer than a board of trustees would be. But a less centralized approach will probably bring about better outcomes.)

I wish to limit my discussion to instances when a scholar speaks ex academia. When the scholar is speaking as a colleague or teacher, a different, probably higher, standard of civility should apply. When speaking ex civitate (as a citizen), a lower standard should apply.

I live in the real world and realize that when someone who is introduced as a “Professor of X” at a political rally, whether that person is speaking ex academia or ex civitate is probably an open question, and his or her employing institution is well-advised to err on the side of more speech. If that institution is a state-run institution, then well-advised approaches something like “categorically should be required to.” I don’t want to insist that “when it’s public, it changes everything,” but if it is the state doing the censuring, it’s almost a freedom of speech issue.

Disciplines have standards about what is discussable and about how what is discussable is to be discussed. Academic speech—properly limited to those situations when the scholar is speaking ex academia and not, say, as a citizen, as a teacher, or as a colleague—can be legitimately restricted based on those standards. And civility can be one of them.

*Yes, I realize I am shifting back and forth between the “he or she” and “they” formulations. I have no excuse. It just seems, to me, to flow better sometimes one way, sometimes another.