Category Archives: Hospital

So last week, we had an eye appointment to check up on Lain’s intermittent lazy eye. Coincidentally, the day of the appointment, Lain started getting some redness and puffiness around the eyes. Not “she’s been crying” redness/puffiness. More like an allergic reaction or some sort. One thing about Lain is that she doesn’t talk much. We have made some progress there, but it’s still a struggle. It can be easy to think that because she doesn’t she can’t hear or understand. But she understands. And she understood her mother and I were talking about some sort of problem with her eyes. And then talking about more problems with her eyes.

After we got there, Lain got an eye test. Before that happened, the tech asked what the concern was with her eyes. Lain, usually the quiet one, spoke up in defiance, “It’s only bad when I don’t blink. When I blink it’s okay” blink blink. So, evidently, she had been dealing with some dry eyes? That might have helped explain the redness. In any event, she seemed to do okay with the eye test and identifying the little images. We were lead to a waiting room where we waited for quite a while.

The next round was with the doctor himself. She got her eyes dilated, which we were not really expecting. He checked her eyes and discovered that the bow-eye really had returned, except (a) it was not nearly as bad as before and (b) this time it was both eyes. That second part is actually better than one eye because they sort of play off one another. I started to notice something in her demeanor, however. She started looking… guilty. Like she had done something wrong. Or she was bad. I can’t quite say how I picked up on those signals, but I did.

The dilation made her vision blurry and uncomfortable. As we were driving home she said “Closing my eyes doesn’t work anymore!”

To recap:

- She overheard us talking about problems with her eyes. On some level, took it as criticism.

- Had eyes that didn’t feel especially well.

- Took an eye exam which involved being asked to identify things she couldn’t identify (Because, of course, they keep going until you can’t get them anymore.)

- She gets these things put into her eyes. Further information about her eyes having a problem.

- She can’t see anymore.

Needless to say, it ended up being a pretty traumatic evening. I really can’t recall if they’d told me that they were going to dilate her eyes. I wasn’t even sure that was what happened until afterwards, because they never gave her the famous sunglasses you wear after. In any event, she hadn’t really been prepared for anything except the implication of not being able to see. Then, of course, she couldn’t.

So, not my best day.

Granted, if you had ever asked me I wouldn’t have said “But for smoking, I would be the picture of good health!” but for any individual problem, I’d attribute to the smoking.

Smoking was responsible for quite a bit of it. Especially, as you can imagine, the lung stuff. I learned this when I switched from smoking to vaping. It took longer than expected, but eventually a lot of the problems I’d had did start getting better. But not all of it. Which is consistent with using a product that has some of the dangers of smoking but not most of them.

Now I don’t vape anymore. And some of the remaining problems went away. I don’t know how much of it is attributable to quitting the ecigs and how much of it was attributable to other lifestyle changes that occurred at the same time. I quit vaping and started eating healthier at about the same time. This wasn’t a coincidence – I wanted to make sure I didn’t start putting on weight I couldn’t afford to put on. So I’ve lost more than 20 pounds and am rarely gorged out. The combination of the two has given me new levels of energy. I feel a lot healthier.

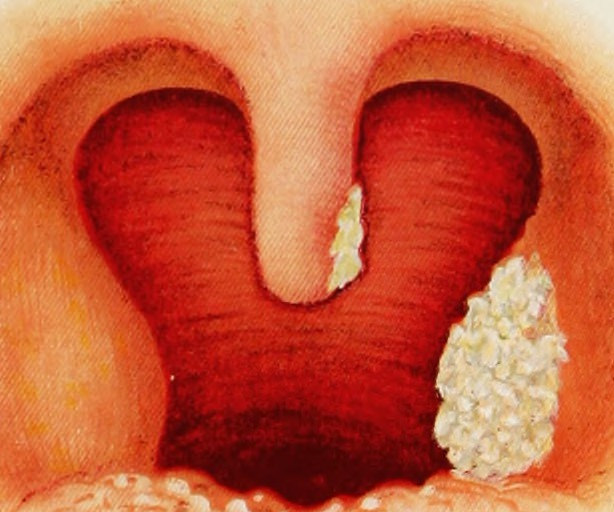

Right now, though, it hurts to swallow. Eating isn’t especially pleasant. My uvula is swollen something fierce. It’s the exact sort of thing that used to happen not-infrequently when I was smoking. The solution has always been “cut back on the cigarettes.” I would and it would get better.

But I can’t cut back from zero. My fallback problem and solution is gone and I don’t know what to do but… I don’t know. Wait I guess? So weird.

I am also reminded of all those times I cut back on smoking when it may have had nothing to do with smoking at all because the swollen uvula happens anyway.

Walking back

It’s presumptuous to criticize members of a profession for acting “unprofessionally,” especially true when I have not acquainted myself with the specific norms of that profession. I did that when I said recently that some mental health professionals “are acting unprofessionally and to a certain extent dangerously in their public diagnoses” of Mr. Trump. Part of what I meant was that mental health professionals ought not to comment publicly on a public official’s mental health.

I no longer believe that. Dr. X–both in his comments here at Hit Coffee [for example] and in some posts at his own blog [here and here]–has convinced me that it’s sometimes appropriate for mental health professionals to make such public commentary and that whether or not it’s “professional” is more arguable than I allowed.

Cautions are still in order

I still urge caution when it comes to public diagnoses, but before I proceed, I’ll note a few terms I am probably using wrong, or at least too globally. “Mental health” and “diagnoses” here in this post are catchalls and may not necessarily encompass what public commentary on public officials is really about. “Mental health professional” is a broad term, too. It can include MD’s, PsyD’s, PHD’s, LCSW’s, and probably others–the key point is that I’m referring to people who are licensed or otherwise credentialed to counsel others or to people who study mental health academically. While my use of these terms is sloppy, I ask your indulgence.

Now, on to the cautions…

Caution #1: “can’t” is a sliding scale

It’s important not to confuse the general sense and professional norm that such commentary is “improper” with a strict prohibition against such public commentary. I understand the Goldwater rule is somehow encoded into the American Psychology Association’s code of ethics. I suspect, however, a mental health professional who offers public diagnoses does not usually risk being hauled before an ethics board or otherwise sanctioned in the same way he or she might by, say, inappropriately breaking confidentiality.

Anti-caution: We should presume that professionals take the established norms of their profession seriously. Even if they disagree with the norms and seek to revise or ask others to reconsider them, we should presume the professionals feel in some way answerable to those norms or at least believe the norms something that merit discussion and are not to be lightly disregarded. Even without a strong enforcement mechanism, these injunctions still act in some ways as a prohibition.

Caution #2: There is never enough information

I submit that any public diagnosis has to be upfront about what is not known and ought to be open to the concern that the diagnosis might be too hasty. In the meta-sense we just cannot see into other people’s minds. In the non-meta-sense, there’s always something we don’t know about others’ history or actions or influences.

Anti-caution: Thus is it always and everywhere. No matter how much is known there are always unknowns. And yet, we have to come to conclusions and mental health professionals are no different.

I am informed that in at least some cases, the mental health professional can diagnose an individual in a matter of minutes. I am also informed that in other cases, mental health professionals may be called upon to create psychological profiles of others whom they have never met (say, psychological profiles of employees or profiles of foreign leaders for state intelligence). And regardless of these examples, some persons’ actions do demonstrate what they are likely to do in the future, and if a mental health professional can yield discipline-specific insights into those actions that a layperson cannot offer, then that’s probably okay.

Caution #3: my corollary to the McArdle rule

Megan McArdle often says that just because there’s a problem doesn’t necessarily mean there’s a solution to the problem. My corollary is that just because a public diagnosis is correct doesn’t mean it tells us what to do with the person so diagnosed. (I’ll add here that a good model is Dr. X. He may offer opinions grounded in his area of expertise, but when he discusses policy solutions he takes care to distinguish what his expertise can and cannot tell us.)

Anti-caution: My corollary doesn’t mean such public diagnoses are worthless. A diagnosis might very well and very rightly warn us, for example, against false assurances that someone will “pivot.”

Caution #4: there will be blowback and it will be unfair

In one of my posts, I referred briefly to objections that Rabbi Michael Lerner of Tikkun magazine has about public diagnoses. I don’t agree with everything he says there, and I agree with less of it now that I’ve heard Dr. X’s counterpoints. Still, the following objection from Mr. Lerner rings true to me:

I believe that making these kind of diagnoses without the benefit of having a carefully constructed private relationship with the public political personality being analyzed leads many of the tens of millions of supporters of the political character who has been labeled in this way to believe that implicitly they too are being judged and dissed. This plays into a central problem facing us in the liberal and progressive world….When we use the kind of psychiatric labeling suggested by those who insist that Trump is a clinical narcissist, that is heard by many who support him as just a continuation of the way the liberal and progressive forces continually dismiss everyone who is not already on our side as being racist, sexist, homophobic, xenophobic, Islamophobic, anti- Semitic, or stupid. This makes many of these people feel terrible, intensifies their self-blaming, but then often generates huge amounts of anger at those who have made those judgments without ever actually knowing the lives and details of the people that are thus being dissed. And this contributes to the ability of right-wing demagogues like Trump (not a psychiatric term, but a political judgment) to win support by telling a deep truth to many Americans: “many on the Left know nothing about your lives, but they have contempt for you, think that if you are white or if you are a male you are specially privileged and should spend your energies learning how to renounce your privilege.”….

First, I should say my quotation is deceptive. The ellipses elide quite a bit. If you go back to read Lerner’s comment in full (I’m quoting from his point no. 4, but I recommend reading all his points), you’ll see his argument is not merely pragmatic, but enmeshed in a broader, ideological critique of the faults he finds with capitalism and meritocracy. I don’t necessarily share that broader critique and if I hadn’t elided those points, the quote would have been not only longer, but would have seemed more contestable as well.

Second, what Lerner seems to me to be saying (in part) is that however accurate a public diagnosis, it might elicit a stronger reaction and in the process do little good. His point is at least partially about prudence. We live in the world, and the world is going to react. It’s not fair, but that’s what will happen.

Anti-caution: We out not overlearn that lesson and make an idol of prudence. If someone speaks the truth, that is a value unto itself. The truth is an end. If that truth is commanded or informed by one’s professional memberships and professional training, then sometimes (maybe always?) it must be uttered and pursued, regardless of prudential considerations. And as Mike Schilling Over There has reminded me, the principal bearers of blame are those who don’t acknowledge the truth and those who create or pursue or gainsay the lies.

If you’re right, you’re right

I’ll probably never be comfortable with public diagnoses. But that said–and in contrast to a point I made very recently–those public diagnoses of Mr. Trump that I’ve seen seem to be correct. Even if they’re not correct, they’re correct enough. Mr. Trump’s actions have shown him to be a dangerous, petty man. So I’ll end where I began above. I retract my blanket statement that mental health professionals ought never issue public diagnoses of public figures.

This OP is a review of George Simon Jr.’s Character Disturbance: The Phenomenon of Our Age (Little Rock: Parkhurst Brothers, 2011).

Simon’s thesis

Simon wants to warn lay readers about, and advise therapists on how to treat, what he calls “character disturbance.” In its more severe stages, character disturbance leads to “character disorders,” among which we can see varying degrees of personality styles that in their more extreme form might include what we know as pathological narcissism, “borderline” behavior, and sociopathy and psychopathy. We can identify character disturbances by choices people make, unfettered or insufficiently fettered, by the feelings of guilt and shame that afflict the rest of us.

Simon contrasts disturbed characters with “neurotics.” These are susceptible to “the conflict that rages between primal urges and qualms of conscience.” (That quotation comes from a blog post Simon has written. But he says basically the same thing, if less quotably, on page 13 of his book.) The average layperson and most therapists too often treat disturbed characters as neurotics acting from neurosis-like motivations. It’s more useful, however, to consider that disturbed characters simply do what they do to get what they want as soon as they can and with the least amount of work possible. We should hold them responsible for their actions, and therapists should use Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (with a focus on the “behavioral”) to give them the tools to change.

Character disturbance is the “phenomenon of our age” because our present-day society and culture encourage people to value their self-esteem over their self-respect. People with character disturbance already have a high self-esteem. They just don’t have the self-respect necessary to feel shame at what their actions show them to be.

The myth of our disturbed age

The book’s subtitle (“the phenomenon of our age”), preface, epilogue, and incidental remarks throughout all point to two questionable assumptions. The first is that character disturbance and character disorders are on the rise. The second is that the manner in which our current culture promotes and condones those ways of acting is unprecedented or somehow unique. Both assumptions imply that our current “near epidemic” [p. 14] is new and dangerous and threatens to undermine “the very foundations of our free society.” [p. 19].

I defer in part and dissent in part. I defer to Simon’s claims about his profession (he’s a former therapist, now writer). He says that therapists in the US are generally trained in the “classical” model of neurosis, with nary a regard for treating character disturbance as a thing in itself. This classical model does a poor job of treating individuals with character disturbance so that in recent decades, therapists whose clients have character disturbances do not treat them effectively. If Simon is wrong on these points, that’s something someone with more knowledge than I about the mental health professions and clinical practice can pursue.

I dissent, though, that we can know with Simon’s confidence that character disturbance is more prevalent now than before and that “self-esteem culture” is somehow unique in the way it encourages character disturbance. Maybe self-esteem culture from ca. 1970 onward condones and encourages character disturbance, but other cultural trends from different eras could plausibly have done the same. I offer as one example white supremacy and the “lynch law” it inspired in the era of Jim Crow. You can probably think of other examples.

I dissent also because it probably doesn’t matter. Whether character disturbance is more prevalent, less prevalent, or about as prevalent as before, it is still a problem that needs to be addressed. If it is indeed a “near epidemic,” then I guess we need to take more assertive measures, rethink our notions of crime and punishment, or go beyond the “political correctness…and the tendency to put personal beliefs and interests ahead of the general welfare”–all of which “impair our ability to conduct an honest discourse and debate.” (p. 252).

But any “honest discourse” has to consider the limitations of what we know. One of Simon’s key points of evidence–our rising prison population–could have other causes in addition to increased incidence of character disturbance. One might argue that the rising prison population represents society taking a firmer stand against character disturbance and disturbed characters are now facing their comeuppance. I don’t endorse that argument, but it’s consistent with Simon’s evidence and yet also runs against the point he wishes to draw from that evidence.

Continuums and sharp distinctions

Simon posits a “continuum” between neurosis and character disturbance [p. 29]. Someone is neurotic to the extent that they don’t have a character disturbance. Someone has a character disturbance to the extent that they are not neurotic.

Simon also notes the promise of a third way out of the continuum and toward what he calls “self-actualization altruism.” Those who approach this altruism “freely and completely commit themselves to advancing the greater good. They are not neurotic because they have no driving desire to avoid guilt or shame for doing otherwise. Also, they’re not out for personal glory or to be revered by society.” [p. 29, italics in original] He doesn’t dwell on that point. In fact, he’s skeptical that there is a third way out and suggests that for practical purposes his continuum makes more sense.

But even so, I’d like to see more discussion about the continuum than Simon offers. Too quickly he jumps from discussing the continuum to distinguishing between neurotics and people with character disturbance. He does not discuss the positions on the continuum where many (most?) of us likely fall. Maybe the turn toward “self-actualization altruism” happens never or only rarely. But is there then, as an alternative, an optimal place on the continuum for us to be?

Such a discussion is probably beyond the scope of the book. Perhaps Simon needs to draw sharp distinctions because 1) his audience includes laypersons like me as well as experts like him; 2) his goal is to warn us about character disturbances and advise us on how to deal with them; and 3) you can cover only so much in any book and still have it be readable.

So…you know it when you see it?

Let’s grant that for sake of readability Simon must make sharp distinctions between the character-disturbed and the rest of us, but how do we know who the character-disturbed or character-disordered are? He gives some clues, especially in Chapter 6, “Habitual Behavior Patterns Fostering and Perpetuating Character Disturbance.” Most of these patterns boil down to denying or deflecting responsibility for harmful actions.

But in a broader sense, how do we know, especially in the “edge” cases where someone is character “disturbed” but not badly enough to be character “disordered”? How do we–especially the laypersons who seem to be part of Simon’s target audience–discern whether someone is character disturbed as opposed to being neurotically disturbed?

Maybe if someone acts like a character disturbed person, we should treat them as such for our own self-protection and let the mental health professionals sort out the underlying causes. It’s probably on balance good to learn how to call out responsibility deflection whether or not the deflector is a disturbed character or merely an anguished neurotic. In some cases, it’s probably better to simply disengage regardless of where the deflector falls on the continuum.

Maybe we shouldn’t seek to “know.” Maybe judgment is for the Lord, and discernment is for a competent and licensed mental health professional. But that doesn’t sit well with me, either. One purpose of Simon’s work is to warn laypersons like me about these people. And while provisionally speaking I can learn a lot about how to respond to responsibility avoidance, part of how I respond depends on my general assessment of their character. If someone resorts to the trick of changing the subject when I bring up a problem it matters a lot to me whether that’s a one-off or part of a pattern of behavior.

Maybe the trick, then, is to find patterns. But there are patterns and then patterns on the patterns. Maybe I’ve just been lucky, but even the people I’ve known who I consider “character disordered” sometimes defy their own patterns.

The problem of suffering and compassion

My concern about knowing or discerning plays into another concern. If we actually have–and can say with confidence we have–an according to Hoyle disordered person before us, what role ought our compassion toward that person play?

Simon seems to say that the first compassionate thing to do would be to empower and help the victims. The second compassionate thing would be to help disturbed/disordered characters learn how to act differently. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (with an emphasis on the “Behavioral”) can help–provided the disturbed/disordered character accepts responsibility for his or her actions and actually is willing to do what is necessary to change.

What about before the magic moment(s) when the disturbed/disordered person realizes they need to change? I think Simon would say the best we can do is call them on their tactics and make them take responsibility for what they do. In those cases, “compassion” is beside the point.

But I’m left to wonder, do disturbed/disordered characters “suffer”? Simon seems to say no, at least not as “neurotics” do. Or if disturbed characters do suffer, it’s only to the degree that they’re also neurotic (remember the continuum above). Disturbed/disordered characters are basically out to get what they want. Simon might concede that getting everything one wishes betokens a deeper and underlying, unhappiness or suffering. But I think he would suggest that we should focus on the behaviors and bracket the other types of questions as not useful.

Parting thoughts

Neurotics come off pretty good in Simon’s book. To the extent that he’s targeting a lay audience, he’s primarily targeting neurotics–and perhaps also the “self-actualizing altruists”– and not the disturbed characters qua disturbed characters. Neurotics make bad choices. But the key to helping them is work through the underlying issues, whatever those may be, in addition to introducing them to better coping behaviors.

Disturbed characters are different from you and me, especially if their disturbance is extreme enough to mark them as “disordered.” There’s hope for them, to be sure. At one point (I can’t find the page number), he suggests that even those we’d call seriously psychopathic might ultimately attain something like redemption or rehabilitation. But he seems to want our takeaway to be that they are the bad guys (and gals). And we, who presumably fall somewhere on the “optimal” range of the “neurotic”/”disordered” continuum, are the good people just trying to survive. That bothers me, even if he’s right. Especially if he’s right.

There’s something missing. Periodically, Simon hints that he too was once been a disturbed character, too. He refers (without specific examples) to other times of his life before he saw the light and started to change his behavior. He doesn’t go into detail. And he probably shouldn’t because that’s not the book he’s to be writing. However, if he ever chooses to write that book, I’ll be sure to read it.

Dr. X, a friend of Hitcoffee, has warned against what some mental health professionals call the Dark Triad. This triad is, to quote Dr. X, a “personality organization that comprises three psychological traits: psychopathy, narcissism and Machiavellianism.” People with that personality organization are dangerous. They are a problem that needs to be dealt with, especially if they are a coworker or in a position of responsibility.

What do we do with such people? In the comment thread to that post, Dr. X suggests that we fire them. To me, the obligation to fire implies that we shouldn’t hire in the first place. If the dark triadic person is not independently wealthy and yet can’t or shouldn’t be hired, how should he or she fend for themselves? Perhaps once properly identified–either through that person’s actions or through some sort of deep analysis–then we ought to consider civil commitment, or prison if justified. Or you can do the Philip K. Dick option: hunt down the androids and eliminate them. I reject that “solution” as does Dr. X and most (all?) others I”ve heard speak on it. But the terms of the discussion are consistent with certain conclusions.

Absent in the discussion on that thread and in the material Dr. X cites (or at least in the quoted portions of that material…I didn’t read the linked-to articles), is a discussion of whether this personality organization is just how or what someone is, or if it has a (personal) history. If people develop into that organization or develop out of it. Not to call this an illness–it’s not clear to me that the language of “personality organization” is a language about illness–but…is there a cure? Or are people just like that?

I’m obviously uncomfortable with the idea. Maybe it’s naivete or wishful thinking. If such people exist, then they exist whether I like it or not. If almost by definition such people don’t seek to change or improve or grow, then they don’t. Sometimes survival and defense of the common good are important. My wish that such people who would imperil either don’t exist doesn’t mean that they don’t.

These discussions remind me of the “mark of Cain” from Genesis. I thought it would be cool to incorporate an allusion to that story when talking about such people. But then I actually read the story, probably for the first time since I was a child. The story starts out as I remember. Cain kills Abel out of jealousy or envy or whatever. The Lord punishes him: “When you till the ground, it shall no longer yield its strength to you. A fugitive and a vagabond you shall be on the earth”

But it doesn’t end there. Cain complains that it “will happen that anyone who finds me will kill me.” To that the Lord commands that “whoever kills Cain, vengeance shall be taken on him sevenfold.” And he sets a “mark” on Cain to warn people not to harm him.

I’m no expert in Biblical interpretations, and I imagine that that passage has been interpreted and reinterpreted through the ages. There’s also a point of unclarity. The referent “him” on whom vengeance is to be meted sevenfold strikes me as amphibolous, at least in the version I’m quoting: I assume the vengeance is to be meted against the one who would harm Cain, but perhaps Cain is the recipient of the vengeance?

Still, the “mark” of Cain seems on my uninformed reading to be the opposite of what I had thought. It strikes me as a mark of mercy, or perhaps mercy tempered by a warning. People are not expressly forbidden to be wary of him or to stop him from further crimes, but they are forbidden to harm him.

Again, there may be other ways to interpret that story, and one might legitimately question whether that story ought to be a guide to anything. But that story exists and I can’t shake it, just like I can’t shake the possibility that dark triadic persons exist.

Rabbi Michael Lerner warns against psychoanalyzing/diagnosing Mr. Trump (or any political leader, for that matter), especially when such psychoanalysis is intended as a tool for opposition. He points out that it’s questionable to diagnose people without working with them for a long time in a therapeutic setting. Rather, he says, one should focus on actions instead of on the internal demons of one’s opponent. (Mr. Lerner lists other reasons as well. Read the whole thing.)

I’m inclined to agree. I get very uneasy when I read of a psychotherapist or other mental health professional diagnose a politician with a disorder.

Occam’s Razor can do some good here. If Mr. Trump is unstable, erratic, or unpredictable, his actions by themselves speak to how much we can trust him or how competent he is. Whether the diagnosis is right or wrong, we don’t need it.

Or mostly we don’t. Mr. Lerner’s warning is an “editorial note” to another piece, “Trump as Narcissist,” by Michael Brenner, also found at the above link.* Brenner makes several arguments that stand or fall on their own. But his key point is that Mr. Trump is a narcissist and we cannot expect the demands and incentives of the presidency to tame his narcissism.

That argument is marginally informed by whether Mr. Trump really and truly suffers from narcissism. If he does, there’s less hope that he’ll mature and grow into the presidency. If he doesn’t, there’s slightly more hope. And if a 25th amendment solution is at all in the offing, then maybe psychological unfitness is a way to invoke that process. (At the same time, I’m not sure we really want to invoke that process, and I am especially wary of admitting to that end testimony from mental health professionals who have not even met with Mr. Trump personally.) So…maybe diagnoses of the sort Mr. Brenner offers do some good after all.

But the argument that Mr. Trump will grow into the presidency doesn’t rely only on the proposition that he’ll become a better person. It also relies on the claim that our system of checks and balances might actually work and that the federal bureaucracy will do what bureaucracies do and somehow condition what Mr. Trump can accomplish. We may of course doubt whether any of this will happen or if it does, whether we’ll welcome what the country would look like afterward. (For example, I’m glad that Michael Flynn has quit the National Security Agency, but I also share Noah Millman’s concerns about the intelligence leaks that seem to have prompted his ouster.)

And for the record, I don’t believe there’s something epistemologically magical about the “months, or sometimes years” of working with a client that Mr. Lerner says is necessary to determine if a person suffers from a disorder. I acknowledge that the the diagnoser probably has to always base his or her decision on incomplete information. So maybe it’s not entirely fair for me to claim the public diagnoses lack sufficient information.

That acknowledgement, however, doesn’t change my mind that such health professionals are acting unprofessionally and to a certain extent dangerously in their public diagnoses. They’re contributing to a discourse in which mental illness is seen as something shameful or to be feared. To my mind they’re weaponizing techniques that originally were meant to help or at least understand people.

Such is not their intention, and it’s not everything that they’re doing. Some mental disorders and perhaps even “personality organizations” ought to disqualify a person from certain positions of responsibility, among them the presidency. When an apt case presents itself, then maybe these mental health professionals are doing a service in highlighting it. And as even Mr. Lerner notes, there is something to be said for noting certain “styles” of politics and cultural expression. He cites Christopher Lasch’s study of the American “culture of narcissism, and I could cite Richard Hofstadter’s essay on the “paranoid style” of American politics.

Maybe there’s no “pure” approach. Maybe some harm has to be done for a greater good. I will probably not convince these mental health professionals otherwise. But I urge them to at least acknowledge and more forthrightly address the dangers of what they’re doing.

*If you read Tikkun Olam a lot, you’ll find that Mr. Lerner often attaches editorial comments to essays he publishes but disagrees with.

For Linky Friday, I had an item about the c-section rate and whether it may promote evolution towards big heads. In the comments, Kristin Devine linked to this article, about c-section rates:

Experts say that even total C-section rates—which include cesareans for all births, not just the low-risk ones we focused on—should rarely be high. “Once cesarean rates get well above the 20s and into the 30s, there’s probably a lot of non-medically indicated cesareans being done,” says Aaron B. Caughey, M.D., chair of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Oregon Health & Science University School of Medicine in Portland and a lead author of the new ACOG/SMFM recommendations. “That’s not good medicine,” he says.

When asked to explain their high C-section rates, hospitals offered several responses.

Mark Rabson, corporate director of public affairs at Jersey City Medical Center, described how his hospital, which serves “a diverse metropolitan area with many socio-economic issues,” was working to lower C-section rates by, for example, reviewing the care of all providers whose cesarean rates are above 30 percent and offering them assistance in how they manage patients during labor. In addition, he says the hospital is now using midwives, healthcare professionals trained to avoid intervening in childbirth unless medically necessary, and people fluent in multiple languages to educate patients about cesareans.

Patricia Villa, a spokeswoman for Hialeah Hospital, told us “while there are many factors that impact a woman’s decision to have a cesarean section, we are focused on driving improvement in this area.” She also noted that the hospital had been recognized by the March of Dimes for it’s efforts to prevent elective early deliveries before 39 weeks.

Photo by koadmunkee

My wife is the type of person to hold the line. I’m frankly not sure that I wouldn’t find some sort of way to rationalize interventions.

But while people know about that aspect of it, and probably know that a lot of women pressure their obstetricians for c-sections, that’s really only a part of the equation. The other part involves decisions that the OB makes well prior to the c-section decision. Intervention begets intervention. If a woman gets an appointment for induced labor, a future c-section becomes more likely. If she gets an epidural, a c-section becomes more likely. If labor is sped along through other interventions, c-sections become more likely. Why? Well, as best as I can figure, the more that a hospital intervenes, the less control the body has over the process. So even if two physicians have the exact same philosophy towards c-sections specifically, their philosophy on earlier interventions may lead to different c-section rates. And a woman’s chances of getting a c-section may depend not just on the obstetrician or the hospital, but the specific anesthesiologist on duty and how aggressive their philosophy is.

In the map on Kristin’s article, you notice that a lot of rural states have lower c-section rates. That’s at least part of why. Clancy’s employer in Arapaho didn’t even offer epidurals. The less resources, the less earlier intervention. The less earlier intervention, the less likely a c-section is to become necessary in the first place. My wife’s c-section rate isn’t just low because she views it as the Option of Last Resort, but because she’s not an interventionist generally (in obstetrics and elsewhere).

So it’s not just a question of whether a c-section is medically necessary, but also whether it becomes medically necessary along the way. Both of these things are going to depend on a lot of things like obstetrician philosophy, hospital policy, resources, other personnel, and (as important as anything else) patient philosophy. Whether they want an epidural has a cultural context, and that’s going to vary from place to place. Whether a woman will be the only person she knows that had a c-section, or whether she’s been told that’s the way to go. Whether she lives in a place where people read Mother Jones, or Newsweek.

Right now we live in a culture where, in addition to all sorts of other incentives, c-sections are normal and giving birth on hands and knees or underwater is considered weird and unnatural. Because intervention begets intervention (both psychologically and medically), and our health care system is an interventionist one from top to bottom, I am skeptical that we’re going to see change any time soon.

Over There, Tod writes about Theranos with some stuff that didn’t make it into an article he wrote for Marie Claire.

I have some comments on a couple of them. First, about Holmes herself:

When speaking in public, Homes has an awkward, stilted way about her. She’s monotonous and unemotional. While others on Ted Talks vibrantly emote, Holmes just kind of dully drones on. When answering tough questions in interviews, she tightens up and looks nervous, her face a mask of forced smiles.

There’s nothing wrong with that, of course. Lot’s of people simply aren’t good on stage or interacting with people they don’t know, especially on camera. If you’re one of those people, you can sound boring, or look like you’re being disingenuous or hiding something, even if you’re not. The point simply being that when looking for a reason for how Holmes not only got away with doing what she did for as long as she did, but also for how she became a near-universal media darling, the answer “charisma” falls woefully short.

Photo by TechCrunch

The second is about narratives, which I think is important but have comparatively little to add:

No one who had Holmes answer their questions with that answer on national television was under any illusion that Holmes was in any way answering that question, let alone addressing a very real serious public health concern about her product. But no one cared. In every case, the person interviewing her smiles and nods, and moves on to ask her how awesome it is to be the world’s youngest female self-made-billionaire, or what it’s like to truly make the world a better place, or some other totally unserious question that fits the narrative they set out to push before they ever lined up their interview questions.

Theranos became a public health problem because it was in Theranos’s interests to push a narrative that simply and obviously was never true. But it became one too because it was in the media’s interest to do the same.

This worries me about media coverage generally. I was talking on Twitter with someone recently about globalism and how one of the criticisms may be off-base. He asked whether I actually believed what the article said, given that it’s a pro-capitalism outfit and our masters all want us to believe it. I said that I believed it, but acknowledged something important: While I believe it’s true, I believe the media would tell us its true regardless of whether it’s true. I think the media does this about a lot of things, including trade, immigration, and race and gender narratives. Even political race coverage, wherein I believe the experts who say that Trump likely won’t win, but in the event that Trump were going to win, I believe they’d be saying… pretty much what they’re saying now. Which doesn’t lead to a reflexive disbelief on my part, but a persistent skepticism I don’t always know what to do with. But narratives are exceptionally important, and deviating from high society’s favored narratives is costly, which makes it easier for everybody to go along.

The last is a bit more political:

It turns out — and I know this will come as a shock to you — that most states have laws against medically testing people without a doctor’s consent, especially by medical testing facilities using procedures not approved by the FDA. Go figure! Turns out that Arizona also once had laws like this on the books. HB2645 essentially lifted those regulations so that Theranos could begin selling its tests to Arizona citizens.

Unsurprisingly, this strikes me as a more complicated issue. Yes, the Arizona legislature dropped the ball here. And they did so in service of a bad actor. And yet… medically testing people without a doctor’s consent doesn’t strike me as an inherently bad idea. I would say something about unapproved-by-the-FDA facilities and that being a good place to hang my hat, but… well, it’s the FDA. While the FDA might keep a company like Theranos from selling faulty goods, I don’t have a whole lot of difficulty believing they’d approach a good actor the same way.

And in a statement against interest, I believe we require a doctor’s consent on too much. A commonly cited example is birth control. Eyeglasses requirements are a bug up my craw as well. Doctors are too busy, and their time both too valuable and too expensive, to be involved in everything. Which gets to the difficult, nitty-gritty aspect of regulation. My approach here isn’t “Deregulate Everything!” but that some things that sound like a transparently bad idea – such as allowing blood tests without a doctor’s consent – may not be.

So while I can easily see that this particular manifestation of such deregulation is a bad idea, it’s not super clear to me what a better model looks like.

Addendum: Make it four. He mentions former Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist as someone who lent Theranos credibility. I only bring this up because when there was talk of a Third Party thing with a split of the GOP, I brought up Frist on a few occasions. It was said mostly jokey, as someone underwhelming to a group of people who had their eyes on Mitt Romney or John Kasich. Someone kind of dusted off the shelf because “Hey, he’ll work.” Anyhow, one thought I did have that didn’t make me like the idea is how much he cashed in after he left office. The Theranos thing doesn’t surprise me. Notably, though, he sold out in ways that Democrats would approve by speaking positively about PPACA.

If I am to pick one low-cost way for ruralia and other places with physician shortages, it would involve waiving residency requirements:

Dr. Faris Alomran, a British-educated vascular surgeon working in France, says, “My first choice after medical school was to practice in the U.S. In fact, for most [English-speaking] people, in terms of language options, they are somewhat limited to Australia, Canada, and the U.S.”

But he didn’t end up crossing the Atlantic. “In the U.S. I would have had to do five years of general surgery and a two-year fellowship in vascular surgery to be a vascular surgeon. Seven years total. I got an offer in Paris to do a five-year vascular surgery program. They also reduced my training by one year since I had done two years in the U.K.”

Juliana, a physician originally trained in Brazil and currently in an American residency program, agrees that migrating to the U.S. could have been easier, especially if redundant training were removed. “Repeating the residency is not an easy thing, and many times it’s very frustrating. I do not think the internship [that I’m in] will add much to my future career. Having trained in America for the last four months has helped me understand cultural differences [between the U.S. and Brazil], but it has also made me wish I were allowed to skip some steps.”

This article seems to focus on attracting the best and the brightest, though that’s less my primary concern. (It’s a heck of a secondary concern, though!)

There is a perception that doctors aren’t going to come here to work in Idaho, and that may be true for the best and brightest. But there are a lot of doctors who would be willing to come here for a paycheck (which, by international standards, are just fine in Idaho). A lot of them wouldn’t stay there, but some would even after released from a 5-10 year requirement. (Yes, even some non-European ones would.)

I’m not optimistic on this happening, though, because while many argue the requirements are self-enriching gatekeeping, in my experience even those places where the doctors are suffering from the shortage (by having to work insane hours, for instance), they are pretty resistant. It’s a matter of professional pride. If another country (besides Canada) aligned their medical training with ours, it would be possible. But… other countries aren’t anxious to bend over backwards to make it easier for their doctors to leave.

That said, people make the AMA the bogeyman for all things gatekeeping-related, but they’re actually open to it. As it happens, and as I will keep saying from now until the end of the time, they don’t weird very much power. The power belongs to the states, and the medical board within the states. The AMA may have some influence with them, but they are extraordinarily conservative and inflexible institutions as far as such things go. They recognize the problem, but don’t see it as their problem.

And from a more cynical standpoint, the looser the restrictions the less important they are. There is a reason that one particular state ran my wife through the ringer over (her own person) medical records that were destroyed in a hurricane, let the process drag on for over a year, and then demanded another application fee (of $1000) because the original one had lapsed. In a state where her skills and professional interests aligned perfectly with a state, and a shortage precisely where she would have gone.

Across the board, the credentialism is just crazy. My wife has delivered over 1,000 babies, and performed more than 300 c-sections, and she could still never be given privileges in county hospitals covering some 70% of the US population. Doctors just out of obstetrical residency, who have delivered far fewer babies, would have no problem at those same hospitals. It’s a long story as to why this is the case, but the long and short of it is that if she wanted privileges at these hospitals, she’d have to go back to residency for three years. All of her experience would only let her skip a single year.

With the news that CVS stopped stocking cigarettes, it was argued by some (though not many) that they shouldn’t be able to make consumers’ choices for them. James Taranto tried to tie it in to the PPACA’s mandate:

Here’s a thought experiment. Suppose Congress enacted the following statute: “Any drugstore that is part of a chain with 20 or more locations doing business under the same name (regardless of the type of ownership of the locations) shall offer cigarettes and other tobacco products available for sale to its customers.” Call it the Marlboro Mandate.

You may object that this would be a foolish law. We agree, but it would not be entirely without precedent for Congress to pass a foolish law. {…}

By contemporary liberal lights, however, the Marlboro Mandate would be a legitimate exercise of congressional power. The Supreme Court has long held to a highly expansive interpretation of the power to regulate interstate commerce. Thanks to the ObamaCare decision, Congress doesn’t have the power to mandate that individuals purchase a product, though even that would have been an open question if the liberal dissenters had prevailed on that point. But a command to retailers, especially to a nationwide retail chain like CVS, clearly qualifies. In fact, we borrowed the “20 or more locations” language from Section 4205 of ObamaCare, which mandates nutrition labeling on chain-restaurant menus.

He then goes on to try to tie it to health insurance contraception requirements.

The argument fails, though not for most obvious reason that cigarettes are bad and contraception is good. There is that reason, to be sure, though that’s going to fall mostly as a matter of perception, and therein lies the rub. No, I think the most straightforward differences are that neither the contraception requirement nor nutrition labeling actually fall into the level of coercion as forced sales (and stockage) no matter what we’re forcing sale and stockage of.

In the case of the contraception requirement, PPACA doesn’t actually require contraceptive coverage. Rather, they are setting a minimum bar for what constitutes sufficient insurance to justify (a) the tax-exemption and (b) avoiding the penalty for not insuring your employees. This is a distinction with a difference because employers are still free to allow their employees to purchase their own health insurance plans on the exchanges. Which isn’t really a punishment because some employers are voluntarily doing it.

Likewise, information disclosure is not exactly novel with the PPACA.

Where I initially thought Taranto was going with his argument, though, was more interesting where he actually did. Forced stockage actually is a contemporary issue. Even more closely tying in to the Marlboro Mandate, it even involves phamacies like CVS. I speak, of course, of the proposed (and in some places enforced) requirement that pharmacists dispense birth control regardless of any conscientious objections the pharmacists might have.

There are differences here, too. The main objection to the comparison really does fall under the “cigarettes bad contraception good” though I have the same objection as I mentioned above. I believe pretty strongly that contraception serves a valuable purpose that tobacco doesn’t, but others are going to disagree with that and it’s not particularly something that can be proven as it is a matter of morals and philosophy in addition to science. And I can think of other things with health benefits or medicinal uses that we also wouldn’t require stores to carry. Including, for that matter, some contraception like condoms.

The next argument for there being a difference is that pharmacies are pretty explicitly places we go to have prescriptions filled and not to be subject to the moral whims of the pharmacist. There is something to be said for this argument, but going to a pharmacy to have your prescription filled is not the same thing as it being guaranteed that such an item will be in stock.

One of the challenges of laws trying to force pharmacies to stock contraception is that pharmacies make the decision not to stock things on numerous bases. A law in Washington State was shot down by the courts. Why? The law had to make accommodations for the fact that there were pharmacies that didn’t want to stock certain drugs for “acceptable” reasons and the court reasoned (among other things) that disregarding religion as a rationale to decline to carry drugs but allowing non-religious reasoning was de-facto religious discrimination.

My objection to these laws are two-fold. First, the same logic that can be applied to pharmacists with regard to contraception can be applied to obstetricians and abortions. When I bring this up, the response I usually get is that there is a difference between having to perform an action that is immoral and giving someone something that you believe to be immoral. It’s true that there is a distinction there, but there are also distinctions in the other direction. A pharmacy that declines to dispense contraception will not likely be an effective barrier to a woman and contraception, but the lack of abortion providers does appear to have an effect on the abortion rate. I suspect that the real difference is that people are simply more understanding of opposition to abortion than of opposition to contraception.

The second objection is the extent to which this is a solution in search of a problem that justifies it. Here is where people like to lecture me on what I don’t understand about rural America, but the number of places where there is “only one pharmacy” is not one I have actually run across and I have looked extensively. What I’ve mostly seen is that there are places with multiple pharmacies and there are places with none. You could run into a place where there are two but neither offer contraception, but that strikes me as unlikely. If these places were remotely common, I suspect that I would actually hear about places instead of theoreticals.

And beyond that, one of the costs of living in rural America is that things such as pharmacies are more of a hassle. As I said, there are places with no pharmacies. These seem to take secondary importance, however, and I’m not sure why. Though I have my suspicions. If we were really interested in trying to universalize access to contraception, we should be looking more into telepharmacies and pharmacy-by-mail so that we can not only give contraception options to that theoretical place with only one or two pharmacies that don’t offer contraception, but those who simply don’t live near pharmacies.

So what are my suspicions as to why this hasn’t been a greater priority? Honestly, because I think forced stockage has as much to do with animosity towards judgmental pharmarcists than it is the logistical problems that this is actually causing.