Category Archives: Statehouse

In the comment thread of my broken primaries post Over There, Michael Drew said the following:

There’s a literature on the Basic Purpose – I think it’s among other things (obviously) coordination around shared goals, and then disseminating (political) information (basically telling people why they might assent to this or that ruler). The rise of the media age therefore put parties significantly on their back feet compared to earlier times (not pre-media per se, but pre-the notion that a working-class individual might independently gather information from nonpartisan sources, look at who might be a good person to be a ruler, and make that decision on that basis, rather than only based on what the dominant party in their area or for their Group says would be best for them). Parties still do solve the coordination problem – you need to move from a population of a million having, say, 10,000 people they support for Ruler, which is maybe as far as non-partisan information sources could get us on their own, to say 10 or 100. My intuition is that parties exist even prior to what that literature suggests, or at least that they have to exist logically because of that last reason – there has to be some intermediation to get from Many to Few potential Leaders.

That’s a really basic, almost logically necessary reason that parties have to exist. But it’s not some kind of general permission slip from The Sky do what they want. In fact, to me, that they are maybe ordained by logic is precisely a reason to less-credit this claim that Hey, we’re just private membership organizations; unless you’re a member, you have no claim on how we behave.

It may be simply a numbers game, or it may be due to a limitation in human nature, but my intuition strongly tells me that we are condemned to do our politics through parties if we are going to try to govern polities larger than the classical Polis. If they’re that fundamental a part of human society in the age of Nations, then to me there is no reason that it should follow that they should be immune to claims about the demands of democratic justice, merely because they claim to be private organizations. They are seeking to fill a necessary purpose that is necessary to achieve public ends – the coordination of the choice about who gets the power to make and enforce laws (if there are laws). If they don’t want the public accountability that comes (should come, anyway) with that, then they can choose some other aims for their organization. If they’re doing things wrong, including not being accountable to the public (not just membership), then just by being a person trying to live in the society whose public life they seek to influence through coercive government, you have a claim against the ways they are doing wrong procedurally or substantively.

I wanted to unpack this a bit.

There is a natural question on what we mean by “parties,” and the distinctions are different when we talk about how much freedom to give, or not to give them. Parties can be informal alliances between factions in pursuit of a series of mutually-beneficial goals, or it can be a very formal arrangement of organization. The degree of formality given to the parties is quite relevant to the degree of freedom that we give them. Orientationally, the more formal the recognition a political party, the more rules that can be imposed.

In the United States, we have two competitive parties. We have a system that favors not only the number two, but that they be Republican and Democratic. This wasn’t always the case, but there is a reason that the Federalist gave way to the Whigs gave way to the Republicans and yet we’ve had the Republicans for 150 years. The parties adapt over time rather than become displaced, because the barriers to displacement have gone up considerably due to formal changes, such as public finances and party-listed ballots, and circumstantial change such as the nationalization of politics and media.

This may be desirable, or it may not be desirable. It is not, however, immutable. Parties may have existed for some time, as Drew says, but the formalization of politics was indeed a choice. There are a number of things we could do to loosen the grip of the Republican and Democratic Parties. I favor some (IRV) and oppose others (multimember districts), but they are options on the table. These are things that would create more options for parties, and give the existing two less leeway.

Alternately, we can devalue the notion of political parties. We couldn’t eliminate them even if we wanted to, but parties are given quite a bit in the way of privileges. States often pick up the tab for primaries, for example. They also put party affiliation on the ballot, which they don’t have to do (and in some city elections, as well as in Nebraska, they don’t). That’s not even getting into guaranteed ballot access, public financing, and other deferential behavior. All of which may be advantageous to the public at large, but none of it is necessary. Pulling the rug out of those benefits would be extremely disadvantageous for the parties, who would have to foot the bill to communicate to voters who their members are, and would have less leverage over the candidates and office-holders generally.

You can look at cities and heavily-tilted states to have an idea of what informal parties might look like. Back in Colosse, partisanship exists but city elections are non-partisan. No non-Democrat has been elected mayor in recent history, but at any given time there are some on the city council. But where the real partisanship occurs tends to be on the informal level. There is almost always a liberal faction and a moderate/conservative faction. People who follow politics tend to know who is on whose teams, though because it’s not a part of the election process there is more flexibility. A moderate Democrat, for example, knows that when she is up for re-election, she can pick up conservative endorsements and votes to make up for ones lost. There is still a natural pull away from the center because term limits force them to look at running in partisan elections later, but it’s none-the-less a functioning system.

Is an ideal system? That’s a judgment call. But either way, there are options available. What does seem clear to me, though, is that the more privilege we give parties, the more we can ask of them. There are, however, limits to this.

While I believe that there are various levers to be pulled, I believe there is a Permission Slip From The Sky of sorts, in the form of Freedom of Association. We can force parties to make the difficult decision between financing their own primaries or losing ballot designation and having their own nomination mechanisms, but we ultimately can’t make the decision for them. And we can’t say “We want the formal parties, and we want to impose these obligations on you so that we can have them precisely the way we want them.”

All of this is something of a moot point, though, because parties are the government, and the government are parties. Except in states with a referendum process, the parties themselves are gatekeepers of policy. I would like to see some reforms that would open the system up a bit and allow parties to be more easily displaced, but you know who has not only the motivation but the power to prevent that from happening? The existing parties. So even in systems with more flexible party structures, such as Canada, reform is difficult. Almost any substantive reform would hurt one party or the other at least, and would leave both more vulnerable in the long run. And with party leadership threatened to a degree it hasn’t been before, it seems more likely than not that both parties are more likely to want to tighten, not loosen, their hold on the democratic process.

Photo by DonkeyHotey

The Weekly Standard’s Jay Cost is a pretty angry man. A fierce critic of Donald Trump, the primaries did not turn out the way that he had hoped. More to the point, though, he saw it coming. Not Donald Trump specifically, but a broken primary process that was in need of serious reform. Along with Jeffrey H Anderson, he penned an elaborate revamp of the process that would have, if instituted, balanced democratic instincts with establishment prudence. The party paid no heed, and here we are.

Truth be told, I don’t favor Cost’s plan. It would be far too complicated and difficult to understand. If it worked perfectly, it could easily be an improvement over the current system, but it is (as James Hanley described it) a planner’s plan, and bound to frustrate the very people it needs to be sold to. From the party’s standpoint, it would be too expensive. From the voter’s standpoint, they would want to know why they can’t just vote like they used to.

Other people have put forth other radical plans to change the system. James Nevius is the latest in a long line of people agitating for a national primary with a runoff. This certainly looks more attractive to me personally than it did a year ago, but most of my objections remain. A primary calendar allows candidates to build support over time. A national primary would put almost all of the emphasis on media and money, and very little on organization and voter interaction.

Others, like James Hanley, believe that primaries should be done away with altogether because they encourage populism, party office holders shouldn’t be saddled with nominees they don’t support, and committed activists have a better notion of the party interest than casual voters.

A lot of things brings us to the questions, what are primaries for? A lot of people believe that they are mechanisms by which the voters decide who the November candidates should be, but that’s not actually true. Primaries are a mechanism by which a party decides who the best candidate for November is. In the United States, this decision is typically turned over to the voters but it need not be. In fact, in most of the rest of the world, it isn’t. It’s likely to a party’s advantage to have at least a quasi-democratic process in order to make the broader population, and their voters and potential voters more specifically, feel like they are a part of it. (more…)

Vox has a story that is primarily about the voting habits of the wealthy, but talks briefly of education:

There are a few things we know have become very strong predictors of voting Democratic. One is that nonwhite people tend to support Democrats at higher rates than white people do. Another is that the highly educated have become much more liberalover time, making educational attainment a better predictor of voting for a Democrat.

And over time, the top 4 percent has become much more diverse and much more highly educated.

In the context of an article about the wealthy veering towards the Democratic Party, one could easily read this paragraph and conclude that one of the reasons they are increasingly Democratic is that they are more educated, and educated people tend to vote Democrat. You could come to that conclusion because that’s almost exactly what the article says. Almost. It actually makes two comments pertaining to education. First, that the highly educated are becoming liberal. Second, that educational attainment is a predictor for voting Democrat.

Both of these are more-or-less true. Higher education tends to associate with social liberalism, for example. And educational attainment is a predictor for both Democrats and Republicans. Just not in the way that the article implies. Nor in the way that either link lays it out, either. Because the obvious implication of those two statements, that more education generally leads to Democratic voting habits, isn’t especially true unless you look at the data in very specific ways, or look only at one subset of the population.

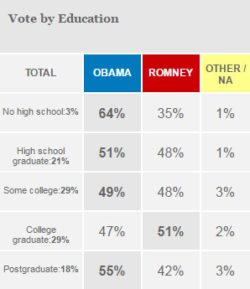

The 2012 data is to the right, and previous years shown below it. You will notice that the one and only group that Mitt Romney wins is college graduates with no post-graduate degrees. This is actually really quite common result. With the exception of 2004, college graduates were the top educational group of Republicans going back all the way to 1988. In 2004, George W Bush did best among “some college” at 54% and then tied among “high school diploma” and “college graduate.” at 52%. For the most part, however, the data to the right is indicative. What it shows is that Democrats do best among the minimally educated and the maximally educated, and Republicans do best in the Great Middle, some college or a bachelor’s degree*.

The 2012 data is to the right, and previous years shown below it. You will notice that the one and only group that Mitt Romney wins is college graduates with no post-graduate degrees. This is actually really quite common result. With the exception of 2004, college graduates were the top educational group of Republicans going back all the way to 1988. In 2004, George W Bush did best among “some college” at 54% and then tied among “high school diploma” and “college graduate.” at 52%. For the most part, however, the data to the right is indicative. What it shows is that Democrats do best among the minimally educated and the maximally educated, and Republicans do best in the Great Middle, some college or a bachelor’s degree*.

So why does the media continue to portray education as having a linear relationship with education when that relationship simply doesn’t exist? There are two explanations that come to mind, neither of which are especially flattering, but both of which are more flattering than “They partisan hacks are trying to trick you!!!!”

So why does the media continue to portray education as having a linear relationship with education when that relationship simply doesn’t exist? There are two explanations that come to mind, neither of which are especially flattering, but both of which are more flattering than “They partisan hacks are trying to trick you!!!!”

Reporters, on some level, simply believe it to be true. So when they look at something like education level and partisan alignment, the data that’s going to jump at them is the data that confirms their impressions. And when they come across data that confirms their impressions, they’re more likely to believe that ought to be a story. A data that doesn’t confirm their impressions won’t necessarily be dismissed as false, but is more likely to be seen as “complicated” rather than a nice, clean narrative like “We’re the educated ones.”

And yes, I do mean “we.” This is an area where it matters that journalists and editors overwhelmingly lean in a particular direction. I mean, do you know how I know that educational attainment doesn’t line up in a linear fashion? Because I took the time to look it up. Why did I take the time to look it up? Because that sounded like an overly simplistic dynamic that didn’t quite correspond with my impressions. There’s that word again: impressions. They matter. Regardless of why newsrooms lean in the direction that they do, it’s not optimal that you have a lot of shared impressions.

In addition to impressions, there is some data. Not the general data, which states what I point out above, but selective data. The data and anecdata that jumps out at you when it confirms your biases. There are three data points that can confirm biases. First, there is a correllation between education level and social liberalty. It just doesn’t cut as cleanly along partisan lines as you might think. More educated Republicans tend to be social liberals, less educated Democrats tend to be socially conservative. Think Country Club Republicans and The Minority Vote.

Second, which is tied to the first, is that the correllation is true among whites. Which makes it sound like “it’s true if you control for race” but it’s not because the opposite holds true for blacks and Hispanics (the educated ones vote slightly less Democratic). And the data for all of this is relatively murky in any event. Too murky to provide any strong narrative, to be honest.

Third, the relationship is accurate if you simply pretend people who don’t go to college don’t exist. If we talk about “more” as getting a postgraduate degree, and “less educated” as merely having a bachelor’s, well there you go. Democrats are more educated. You’ve tossed out half of the electorate and more than half of the population, but those aren’t the people you know, are they?

Which, in addition to confirmation bias, is the source of at least some of this. And is concerning, in its own way. Newsrooms are disproportionately white, and they’re disproportionately educated. The country is (right now) majority white. So when they think of more educated and less educated, they’re likely to be thinking (consciously or unconsciously) “white.” And when they think about who is more educated and less educated, in their world having a postgraduate degree, or a degree from an elite university, does, confirm the bias. Their reality has a liberal bias. I just don’t think they like the omissions that necessarily get them there.

After 2016, this may all be moot, at least for a cycle. It would not surprise me if Hillary did unusually well among those with college degrees and Trump did more poorly. And this could be where the parties are ultimately headed. But they’re not there yet and the trends do not suggest it’s inevitable.

* – This is, it should be pointed out, increasingly what things are looking like with regard to income, which is what the Vox article touches on. Democrats win among the poor, Republicans do best among the middle rich, and Democrats do better and better among the wealthy.

Now we all did what we could do.

Donald Trump, on stage at the first Republican convention for the ‘16 election, was considered a joke, something to make fun of regarding how bad the choices were for the conservative branch of American politics. Against all predictions, he ended up sweeping aside the other nominees while rushing headlong into the nomination. As he got closer and closer, more and more pundits predicted that groups such as #NeverTrump would prevail, saving all of us from the monstrous idea that is Trump.

But Republicans didn’t seem to want to be saved from Trump, and indeed to have been relishing his rise in the fight against Clinton that seems to be coming this fall. They pulled a collective Jack Move, and it seems to be working for them. Don’t get me wrong, there are still plenty of conservatives who want nothing to do with Trumpism, including a few of OT’s writers and commenters.

But the Republican Party doesn’t seem to want those voters anymore; it may be happier without them. For they are the voters who brought out McCain and Romney, two candidates that the Democratic party and its friends in the media were in many ways designed to defeat. The candidates that the establishment wing was trotting out this year, Bush and Cruz, would have been destroyed in a similar vein. And when presented with a possible choice that obviously set off the nation’s elite, with cries of “How Could They!” and “He’s Vulgar!” – the right jumped at the chance, swarming en masse toward the billionaire with the funny/cheesy hat. Why? Why did they feel that they needed to do this? Well, let’s take a look.

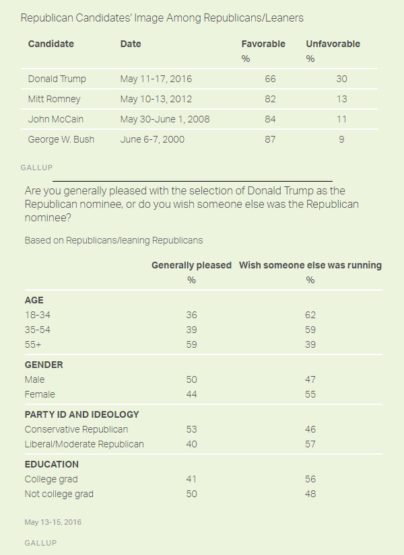

Now, first, define Republicans. Are we including the 60% that voted against him? Are we including the 35% or so that support him only “with reservations”, the 15% who are only supporting him because he’s the nominee? The additional 15% that so far say they won’t support him? Or are we excluding them? Are we also excluding the last two Republican presidents as well? Are we excluding the last nominee? We can define deciding to vote for him only because he is the nominee as “relishing his rise” if we want, and can say that conservatives and Republicans love him by excluding the large chunk that doesn’t, but none of that removes the fact that he is the weakest nominee in terms of party support that we’ve ever seen. While those that still oppose him in the general election are the distinct minority, issues persist. He won, but mostly by wearing down the opposition. Now a win is a win, and he evidently has the support of the establishment and most of the party going into November, but past that we’ll have to see where things stand.

Now, first, define Republicans. Are we including the 60% that voted against him? Are we including the 35% or so that support him only “with reservations”, the 15% who are only supporting him because he’s the nominee? The additional 15% that so far say they won’t support him? Or are we excluding them? Are we also excluding the last two Republican presidents as well? Are we excluding the last nominee? We can define deciding to vote for him only because he is the nominee as “relishing his rise” if we want, and can say that conservatives and Republicans love him by excluding the large chunk that doesn’t, but none of that removes the fact that he is the weakest nominee in terms of party support that we’ve ever seen. While those that still oppose him in the general election are the distinct minority, issues persist. He won, but mostly by wearing down the opposition. Now a win is a win, and he evidently has the support of the establishment and most of the party going into November, but past that we’ll have to see where things stand.

As things stand, Trump has not yet demonstrated any greater capacity to win than Romney or McCain to win yet. But we can set that aside, because electability isn’t entirely the point anyway. There are two dimensions at work here: Electoral prospects and national good.

Electorally, it remains my belief that Trump is not going to win. I fear what would happen if he did, but I’m not especially worried yet that it’s likely to happen. That will change if Trump can start regularly polling above 47% (depending on how close we are to election day). I just don’t think he’s going to be able to get the women votes he’s going to need. But I am and have been pretty firm in my belief that the greater threat of Trumpism isn’t that it’ll lose, but that it will eventually win. I’m not under any illusions that the party needs to appeal to me and mine in order to win. I’m worried about a party that takes the Republican coalition and doubles down on the white identity and wins.

The Republican voters are within their rights to embrace all sorts of ugliness. I am not obliged to be respectful of their decision to do so, however. Nor of muting my opposition to it. Right now this is about my party, but the closer they come to the presidency the more it becomes about the country. This isn’t really about trade policy. Nor is it even about the anti-immigration view. It’s about an embrace of European right-wing sensibilities, combined with ugly movements in our country’s history, more or less untethered by restraint and indifferent to bad acts, lead at the moment by someone whose entire worldview consists of himself and his own self-interest.

The Republican voters are within their rights to embrace all sorts of ugliness. I am not obliged to be respectful of their decision to do so, however. Nor of muting my opposition to it. Right now this is about my party, but the closer they come to the presidency the more it becomes about the country. This isn’t really about trade policy. Nor is it even about the anti-immigration view. It’s about an embrace of European right-wing sensibilities, combined with ugly movements in our country’s history, more or less untethered by restraint and indifferent to bad acts, lead at the moment by someone whose entire worldview consists of himself and his own self-interest.

It might seem tempting to treat this as something that’s a respectable political choice like supporting Hillary, or Bernie, or Cruz… but it’s not. Saying “This is what they want!” does not make it better, it makes them worse. Are there some legitimate grievances in there? I suspect so – far worse revolutions and even bloody revolutions usually do – and I think the party and the country is going to need to look at all of that. But first, the fire needs to put out, and the poor electrical work that started the fire needs to be repaired.

At the moment, it seems that roughly 40% of the party is in the tank for him, another 35% or so have reservations about him and are willing to go alone, and another 15% or so will support the Republican Party nominee no matter what. Depending on how you parse it, this is an enthusiastic plurality or a placid majority. It’s hard to say where, precisely, Trump’s support is coming from. How much of it is the worldview he represents? How much of it is just liking the man? How much of it is hating the other team? How much of it is thoughtless support for their own team? Most people think they know, with their opinions corresponding with whatever they happened to think of the GOP 15 months ago, but it’s going to be pretty important to find out.

The worst possible answer: “They’re really – and intractibly – on board with this. All of it.”

The Washington Post examines the effort to find and field a third major candidate:

An obvious possible contestant is Kasich, who portrayed himself in the GOP primaries as a pragmatist with crossover appeal. Since he dropped out, Romney and other Republicans have tried to persuade him to forge an independent run.

But Kasich’s advisers dismissed the idea. “The governor is not entertaining nor will he run as an independent,” spokesman Chris Schrimpf said.

John Weaver, Kasich’s chief strategist, said of the governor’s courters: “They had plenty of time and opportunity to influence the [GOP] nomination battle in a constructive way, and they didn’t for whatever reason. The idea of running someone as a third party, particularly the way they’re going about it, is not going to be effective and is not practical.”

Has anyone explained to him there is potentially a lot of free food involved?

Alas, it appears that Kasich is not interested. It’s a fine time for him to be completely uninterested in a pointless and futile campaign. While I don’t think his presence in the race was ultimately responsible for the outcome, it conceivably could have been. His strong showing in New Hampshire came at the expense of others, and I can imagine some chain reactions that would have changed things considerably (though most would not have, given the givens).

Next to Bob Gates, his was the strongest name I had considered for the a third-party run. He’s conservative enough that he could have picked up a fair number of extant Republicans who simply can’t stand Trump. Though a lot of conservatives were rubbed raw by his acceptance of the Medicaid Expansion, most of the #NeverTrump people I know were willing to bite the bullet for him in the primary, if necessary, and I suspect they would in the general as well. But he’s also done the whole Apostate Republican thing to have credibility with some free agents who really dislike Hillary Clinton, too. And he occupies an ideological lane not entirely different from Trump’s, to whatever extent ideology matters.

The point here would not be to win, because that would be impossible. It wouldn’t even be to throw the election to the House of Representatives, because that’s likely impossible as well. The goals would be to either (a) take enough of the vote, disproportionately from Trump, to have a tangible effect in the outcome, (b) give extant Republicans a place to park their vote and wait for things to gear up in 2020, and (c) give Republicans in vulnerable districts an “out” where they can endorse someone other than Trump without endorsing Hillary. Even some of those that have supporter “the nominee” would have an excuse to back away, though state parties are scrambling to close the door on that. Kasich would be in a good position to do all of these things in a way that few others are.

The most important number is 15%. Not as a total vote-share, but in polling. If you can get 15%*, then you get in the debates and you remain a potent force. You may not get 15% or 10% on election day, but in this election you should be able to beat John Anderson’s 6.6% and throw a few states. Possibly win one or two, for the right candidate. Kasich would not likely win any states, but would have an easier time getting to the 15%. Mitt Romney would be able to win at least one state and some have suggested as many as five or six, but would have a hard time getting to 15%.

Besides Kasich, most of the other names that come up are either too big or too small. By “too small” I mean that they lack a profile or much of any name recognition. Ben Sasse falls into this category, as do most of the other Republicans that have been more vocally anti-Trump. By “too big” I mean that they have too little to gain and too much to lose. Think Paul Ryan. And some, like Nikki Haley, have a fair amount to gain but a lot of potential to lose. Bob Gates is the only other name I’ve heard that makes sense and occupies largely the same place, but he has no history as a candidate.

Kasich, on the other hand, is just the right combination of things. He has no real future in elective politics. If he had a motivation for running for president, it was to enter the history books. This would help! But mysterious are the ways of John Kasich, and he says “no.”

Tod is kicking off a series on how to fix the Republican Party. Less than entirely interested in getting into the debate Over There, I thought I would briefly share some of my thoughts over here: (more…)

I have to be a little skeptical of Emmett Rensin’s essay on “The Smug Style in American Liberalism” because it captures almost exactly how I feel. I’m tempted to offer some pithy quote and say “read the whole thing.” But that’s boring. Instead, I’ll offer three counterpoints to his piece. Rensin attributes too much power to the style. Rensin’s evidence is dangerously anecdotal. Rensins does not sufficiently acknowledge competing “smug styles.”

Rensin’s argument.

Since the end of World War II and especially since the 1960s, liberals in the United States have increasingly adopted what Rensin calls a “smug style” that turns off people who might otherwise be inclined to support liberals’ programs. This smug style is found when liberals insist they know better than those who might disagree with them on any number of issues or policies. This “knowing better” specifically targets the white working class, according to Rensin. Disagreement with putatively liberal policies stems at best from an undue attachment to less important concerns like “guns and religion” and at worst from base motivations like racism or sexism.

Counterpoint No. 1: Too much power to the style.

For the most part, Rensin is discussing a style and not a substance. It’s not so much what liberals advocate as it is how they go about it. “I am not suggesting,” he says, that liberals “compromise their issues for the sake of playing nice.” He’s more concerned about the role smugness plays in alienating potential allies.

Still he hints that smugness leads to the adoption of harmful policies. He claims that “open disdain for the people they [liberals] say they want to help has led them to stop helping those people, too.” However, he doesn’t elaborate on what this means on a practical level.

I therefore wonder if he–and I–perhaps assign too much power to the “smug” style as a style. Even though I can think of specific policies–even policies I support like Obamacare–that in some ways hurt workers, at some point we have to leave off pointing out smugness and engage in accounting for why and how those policies are harmful.

Counterpoint No. 2: Rensin’s evidence is of necessity anecdotal.

With a couple exceptions, Rensin wisely eschews psychoanalyzing liberals’ latte-drinking inner demons. He focuses instead on what liberals say or what is said in favor of causes liberals presumably support. His examples are many, taken from Facebook and Twitter feeds, excerpts from Jon Stewart’s Daily Show, and other venues.

All to the good for his argument. But the anecdotal nature of his evidence limits what he–and we–can say about liberals’ smug style. First, there’s the problem that what is smug for me may not be smug for ye. Sometimes a joke is just a joke and a barb is just a barb. (And for the record while I can’t stand Stewart’s schtick, I really enjoyed watching the Colbert Report, which is even more unrelenting in its critique of a certain brand of American conservatism.)

More important, we see what some people say on Facebook, but not how those same people interact with others in real life. We see what Stewart does and guess to whom his jokes are meant to appeal, but we don’t see the other things the audience laughs at or how they act when they’re not consuming his brand of entertainment.

Rensin’s argument almost has to be anecdotal. It’s not wrong for being anecdotal. And it’s hard in any systematic way to get at what he’s trying to get at. But we–especially those of us inclined to agree with him–should beware of how far we’re taking the evidence.

Counterpoint no. 3: Other styles compete with liberals’ “smugness.”

Early in the essay, Rensin says, “Of course, there is a smug style in every political movement: elitism among every ideology believing itself in possession of the solutions to society’s ills.” But he mostly lets that recognition drop right there. He quickly redirects the reader to liberal smugness: “few movements have let the smug tendency so corrupt them, or make so tenuous its case against its enemies” as American liberalism.

But let’s dwell a little more on the “smug style in every political movement: elitism among every ideology….”

There’s a libertarian smugness, often called glibness or glibertarianism. While I’m not a libertarian, one libertarian-lite policy I have endorsed is a good example of this. I once advanced the opinion that when considering wages and hours regulations (but not health and safety regulations), I prefer the policy that creates more jobs, if bad ones, to the policy that creates fewer jobs, if better paying ones. While I insist I adopted that position out of sincere concern for people less fortunate than me, I can certainly see how someone who works at or near minimum wage would see my position as smug or glib. At any rate, I’m not going to offer my opinion, especially when it’s unsolicited, to the many service workers I encounter. And if I did offer the opinion, I would be inclined to do so apologetically and in the spirit that I don’t really know what their life is like.

Adherents to non-libertarian conservatism can exhibit “styles” that approach something we can call smugness.

Two examples. One: We’ve all heard the “hate the sin, love the sinner” aphorism. On one level it’s offered, I submit, sincerely, in the belief that we all sin and fall short of the glory and that persistence in sin is detrimental to one’s well-being, perhaps more akin to a sickness deserving compassion than to a crime deserving sanction. But alas, as a slogan it has often accompanied attempts to promote “gay conversion therapy” or to deny the right to same sex marriage.

Two: We don’t have to go back too far to remember that voicing skepticism about the 2003 Iraq invasion signaled to some people that one was at best naive or worse, less than patriotic or supported terrorism. The opponents to the war gave their (sometimes inexcusable) tit to the neo-cons’ tat, but that element from the pro-war side was real, too.

Do religious posturing against gays and pro-war patriotism-baiting count as “smugness”? I’m not sure I’d go that far, but it’s a brand of “knowing better” and dismissing dissenting views similar to the smug style Rensin describes.

But seriously, “read the whole thing.”

As I said above, I agree with Rensin. I don’t do so grudgingly, but gladly. He’s got it right. He uses evidence and logic to come to a conclusion that works for me and that I was inclined to accept in the first place. Therefore on one level, you might read this long post merely as an exercise in finding holes in another person’s argument. And frankly, Rensin could not have addressed my points and still written something readable.

But on another level, I do think those of us most eager to find a “smug style” among American liberals need to consider why the very smugsters we criticize might take exception. The goal isn’t only to win, to see our side through to its notion of the good and the just. It’s also to understand and live with each other because in my view that is part of the good and the just as well.

The American Republic will end someday. That isn’t a particularly novel or edgy observation. It’s quite banal. “Greece fell, Rome fell….” (China hasn’t fallen yet, but its longest lasting dynasties seem to have a shelf-life of “only” a few centuries, so maybe that counts.)

For me the question is when, not whether, the Republic will fall. I don’t know if a Trump presidency will bring about the fall, but it might. Or it might set the Republic on the course toward its fall. Maybe Trump would do it with a bang so loud we’ll know it’s happening.

Or his election will be one more step in legitimizing a “church and king” faction that perhaps has always been latent in American political politics.

Legitimization is not a yes or no proposition. It happens by degrees and in stages. A formal nomination by a major party can legitimize this faction even if the nominee will never win. I’m not the first to make the comparison, but while here was no way Jean-Marie LePen was going to win the French presidency in 2002, getting to the runoff gave him and his constituency a big boost. If that analogy holds for Trump, then his presumptive nomination is a bad thing indeed.

But maybe t the Republic has already fallen. This “church and king” faction–well, maybe it’s not a faction, maybe it’s a “style” of politics–certainly had its antecedents. Maybe the deal was sealed at some point. Maybe Wickard v. Filburn. Maybe Korematsu. Maybe the Cold War national security state and military industrial complex. Maybe the Espionage, Sedition, and PATRIOT Acts (or maybe the Alien and Sedition Acts). Maybe the milling factionalism in our politics and the thousand pinpricks into civil society and individual privacy and democratic governance that might very well be the inevitable consequence of what some call “modernity.”

I once attended a presentation by a professor on Augustus and the end of the Roman Republic. According to him, when Augustus seized and consolidated his power, he did so on the fiction that Rome was still a Republic. Romans still spoke as if they lived in whatever had passed for a Republic ca. c.e. 0. But they also knew who was calling the shots. It was only in retrospect that people saw his reign as the beginning of something new.

Trump is no Augustus. Or at least I don’t think so. I don’t fear or dread Trump as much as the #NeverTrump people seem to. If his nomination–and possible election–augur ill for us, it’s one step of a process that depends on decisions we have already made and on decisions we will make in the future.

I agree with the first part, though am skittish on the second. There is no doubt that with some possible basic exceptions there is not a Constitutional conflict. I don’t think that entirely lets us off the hook, however.

There are a lot of good reasons to have regulation when it comes to childcare. While excessive licensure may be an issue in some domains, it’s hard to imagine childcare without some sort of licensure regime. Parents don’t know what goes on after they drop their kids off, kids are not necessarily able to articulate what’s going on, and parents may not entirely believe them when they do. It’s not like a bad haircut either in terms of actual damage done or in the ability to hold people accountable (in the case of a barber, simply not going there again).

There are definitely limits to this, though. Not just in how rigorous the requirements should be, but where they should apply. Lain’s babysitter, for example, is completely unlicensed. It’s the daughter of one of my wife’s colleagues. She may have some basic training, but certainly hasn’t undergone any rigorous process or anything of the sort. But we leave our daughter with her because we know her family, trust her upbringing, and we’ll take that chance over someone with all of the appropriate paperwork that we do not know. We’ll obviously take the discount as well, though that’s obviously not the issue for us that it is for other people.

I don’t think that’s entirely dissimilar to a church. I think there can often be that same sort of intimate relationship where the common faith and social relationship can stand in replacement of the ordinary markers of trustworthiness. That a parent might reasonably trust their church to look after 15 kids while a private entity needs to cap it at 10 (or whatever). The existence of the regulation makes it so that parents who don’t have a church, or a colleague’s daughter, or whatever can have maybe a little degree of assurance that it’s not a bum outfit that is going to abuse their child. But with that option available, alternate arrangements for others also seems reasonable.

Which is not to say that I want to give churches a pass. Like I say, it’s tricky! Because you don’t want churches running reputable childcare centers out of business on the basis of the lower costs they can achieve through these exemptions. You don’t want someone to set up a center, hang a cross by the shingle, and do whatever they want. This is further complicated by the fact that governments tend to loathe trying to discern genuine faith and the genuine faithfulness of an institution. I can definitely understand why Kazzy in particular, who views things from the prospective of a provider, believes that it’s important for all providers to maintain certain standards of care with no exceptions.

It could also be the the exemptions I might carve out would be pretty worthless anyway. That’s something Kazzy would know a lot better than I do. But I’d be less inclined to support a “religious daycare” outfit that wasn’t actually connected to a place of worship or religious organization that exists apart from the center… though that would likely put me in more First Amendment hot water than what the states are doing. I also might look at churches that offer day care selectively to members of their faith. That may not be workable, either of all of them flat-out rely on outside families. So the end result might be that I end up supporting all of the same regulations as Kazzy and Oscar, if a bit more reluctantly.

Alright, I’m going to ramble a bit about the South here. Don’t know how long this one’s gonna be.

— Asinus Pervicax (@Cato_of_Utica) April 15, 2016

You cannot understand the South without understanding the impact of the Civil War and Reconstruction.

— Asinus Pervicax (@Cato_of_Utica) April 15, 2016

Emancipation didn’t just end slavery. It also wiped out at least a year of US GDP’s worth of real estate ‘assets’.

— Asinus Pervicax (@Cato_of_Utica) April 15, 2016

I don’t have an exact figure, but it’s safe to say at least a quarter of the South’s capital pre-Civil War was tied up in slavery.

— Asinus Pervicax (@Cato_of_Utica) April 15, 2016